Butterfly Effect

Understanding El Nino’s and La Nina’s influence.

If someone told you that the temperature of a body of water 3,000 miles away could affect the severity of winter across southwest Montana, you’d probably roll your eyes. But then, maybe it lingers in the back of your mind, and eventually you just have to look it up, only to discover that that’s exactly what the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) does, which encapsulates both El Nino and La Nina cycles (“little boy” and “little girl” in Spanish).

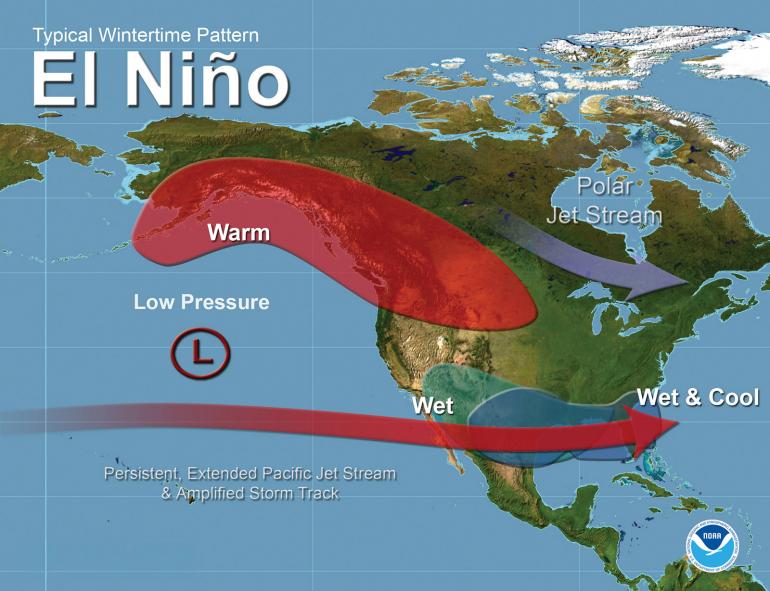

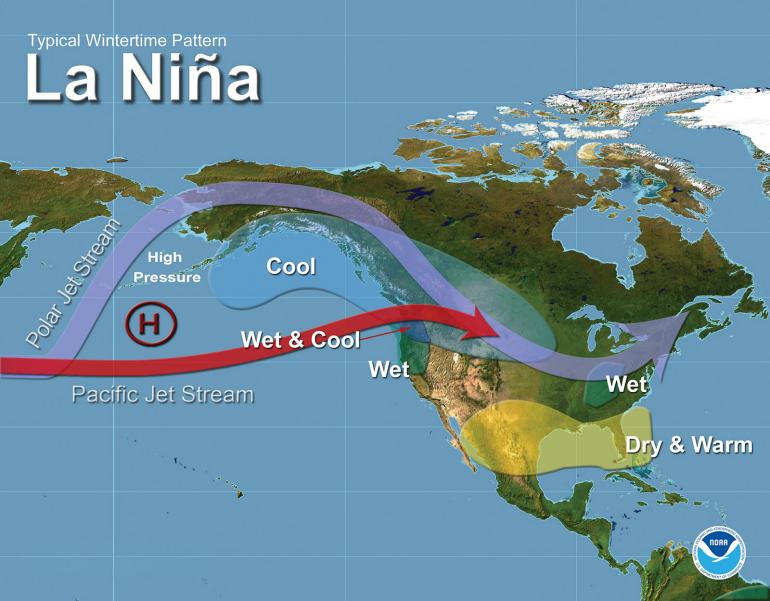

ENSO is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. All it takes to affect our winters is a warming or cooling of the water there from one to three degrees Celsius. That might not sound like much, but this relatively small change has huge impacts on the climate patterns across the world. When the water warms up, we enter the El Nino phase. Conversely, when these waters cool, we enter the La Nina phase.

Generally, El Nino produces warmer winters and decreased snowpacks across southwest Montana, while La Nina nudges things in a cooler, snowier direction. But winter predictions and impacts from ENSO are never that simple, especially here in the Bozone and Montana as a whole. There are plenty of other variables that can affect our winters (however subtlety), including polar sea-ice extent, high-latitude ocean temperatures, sudden stratospheric warming events (those that occur high up in the atmosphere), and local snow cover. What’s more, our mountains throw a curveball into things—they produce local effects that contain drastic differences, from different elevations with vastly different temperatures and snow amounts, to the slope directions (meaning one side of the mountain has many more feet of snow than the other side).

So, where does that leave us? How much stock should we put in ENSO when it comes to winter predictability? Overall, even though predicting and forecasting winters in southwest Montana is difficult, the general trends that El Nino and La Nina cycles predict for the area remain consistent. The thing to remember most is that we’re talking about a probability of seeing higher or lower temperatures and wetter or drier conditions, which are spanned across multiple months and generalized to a large area. There will always be warm and cold spells each winter, and there will always be winter storms that produce tons of snow. Just how often they happen, and how extreme they get throughout the winter, that’s where that probability lies.

To put it into perspective, the current winter outlook provides an optimistic view for skiing at resorts across central Montana, including Bridger Bowl and Big Sky. It gives higher probability for seeing above-normal snow and cooler temperatures this year, leading to a better snowpack. However, as mentioned before, these recreation areas will still see fluctuations and have both warm and cold days, as well as wet and dry spells.

These swings and differences could vary from one mountain to another, even if they’re only an hour’s drive apart. The local effects defined earlier can and will create these differences, despite overall outlooks. Do not, however, be concerned about a dry spell creating bad snow conditions for winter recreation. More often than not, a wet, snowy stretch will eventually follow, delivering the enjoyable snowpack that defines a Montana winter, regardless of what the little ones are doing.

Nick Vertz has a double-major in Atmospheric & Oceanic Sciences and Life Science Communications from the University of Wisconsin – Madison. He also has an M.S. in Meteorology from Iowa State University. He lives in Billings.