Moving Mountains

News from Bridger Bowl for the upcoming season.

Our world is constantly changing, and Bridger Bowl is no exception. After a landslide swept through the ski area this past summer, general manager Hiram Towle says navigating many of the runs will look different this year. With deeper channels and displaced boulders, early-season skiers may have to wait for a deeper snowpack to fill gullies and allow grooming machinery to reach certain parts of the mountain.

For those who can’t resist hitting fresh powder the moment it falls, Towle says safety comes first. Skiers should stay alert for new obstacles left by the landslide and get creative in finding new lines on slopes some have been skiing for years. “We’ve assessed the damage and cleaned up what we can,” he explains. “But now, we’re waiting for the snow to fall to see what it’s really going to look like. Weather has been shaping these mountains for millennia—nature always wins.”

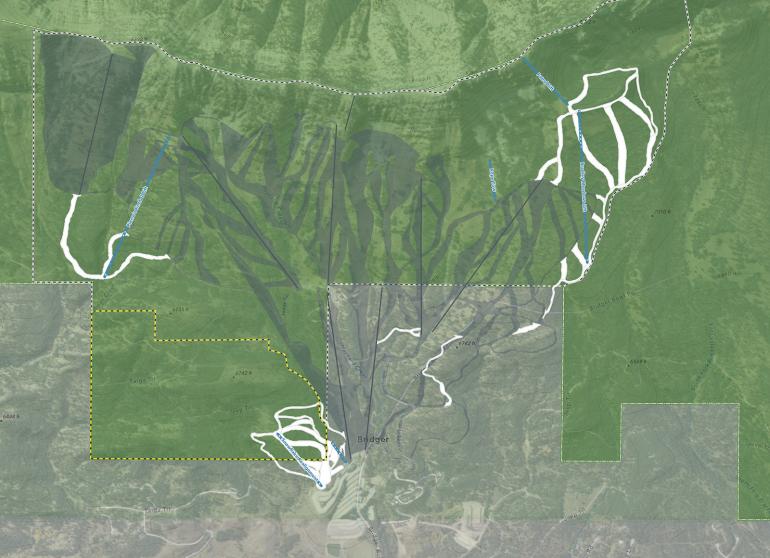

But Mother Nature isn’t the only one reshaping the ski area. Last year, the nonprofit unveiled its Master Development Plan (MDP)—a decade-long initiative designed to increase Bridger’s capacity while ensuring the resort remains welcoming and sustainable for generations. “It’s about keeping a healthy bank account and making sure we can continue to serve this community and reinvest in the mountain to make it as safe and enjoyable as possible,” Towle says.

MDPs are created roughly every ten years. “They live, they breathe, and they’re malleable,” Towle explains. This iteration outlines initiatives to facilitate night skiing, create a new beginner area, expand snowmaking capabilities, and increase overall capacity. While these ideas may seem straightforward on paper, don’t get too excited about night skiing, as the path from concept to reality is long and winding.

Because most of Bridger Bowl lies within the Custer-Gallatin National Forest, any development must comply with the terms of a special-use permit. Like the relationship between a renter and a landlord, Bridger Bowl pays the Forest Service a fee, follows regulations, and acts as a steward of the land in return for the privilege to operate.

The MDP unfolds in three phases. First, Bridger establishes its goals and proposed projects. Next, the plan is reviewed by the Forest Service—a process that can take several months to a year. The MDP is currently in this phase. Once approved, it undergoes analysis and authorization under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

The MDP serves as an overview of the changes Bridger hopes to implement. Each project—from ski lifts to parking expansions—must be drafted, engineered, and budgeted separately. “It’s like building a three-legged stool,” says Towle. “You have to balance lift capacity, skiable terrain, and base area & parking capacity.”

As Bridger awaits the green light from the USFS and NEPA, Towle says skiers can help make this winter better for everyone by carpooling or using Bridger’s free bus to help ease parking pressures. To keep the mountain safe, Bridger offers lessons, workshops, and enforces responsible riding. “We’re not a resort—we’re a ski area,” Towle says. “We want everyone to feel welcome here, whether you’re a gun-slinging cowboy or a ridge hippie.”