Out of Control

The lost spirit of Big Sky.

It’s a tale that’s become all too common among western ski towns: resort monopolies and the ultra-wealthy gulp up property and businesses, resulting in unalterable changes to beloved towns, ski hills, and cultures. And this trend has become the norm. From Telluride to Whitefish and everywhere in between, the story’s the same. Mega-money slithers across the nation and sinks its fangs into our once-tranquil mountain retreats, transforming laid-back hideouts into glitzy, fast-paced, luxury resorts with mink-coat shops, fancy cars, and massive slopeside mansions that mostly sit empty.

Hailing from a land where “Vail Sucks” stickers are commonplace, I’m no stranger to the notion of wealth intrusion. When I was growing up, my mother reminisced about her past life as a ski bum in Vail, talking fondly of days when affluent tourists kept to themselves, and life was centered around days with skis below feet. Often the conversation would turn sour. She’d go on to describe the poisonous change that pushed her, and many locals like her, away from the mountain they loved. The skiing, and, more importantly, the moneymaking potential, was spiraling into what Vail and many resort massifs have become today—a melting pot of fancy buildings, upscale restaurants, expensive lift tickets, and overpriced homes.

In those days, folks were infatuated with Big Sky and enamored by the skiing experience they found: it was big, wide-open, with a sense of romance and freedom that reflected the essence of Montana itself.

For a long time, Montana dodged the opulence that was reshaping other areas, preserving places like Big Sky for the people who cared the most: the skiers. However, what was once true is no longer. Big Sky has changed. What was born as a place by, for, and about skiing, has become something else entirely.

The early days of Big Sky mirrored that of most ski resorts in the ’70s. Quaint. Primarily visited by regional residents and adventurous out-of-staters looking for an affordable yet epic winter vacation. Longtime resident Bill Webster worked at Big Sky in its earliest seasons. “It was just us workers up there the first couple of years or so,” Webster recalls. “It was quite small, too, with four lifts at the time.” Back then, Big Sky was a simple ski area, catering to skiers intrepid enough to drive the long, snow-covered dirt road up from Hwy. 191. There was barely a town, no condos, no Lone Peak Tram, and few people. “In 1975, there were a lot of people in Big Sky looking to find themselves,” Webster says, and the majority of his co-workers were “people whose vehicles broke down in the canyon near Big Sky, got a job on the mountain or at a restaurant, and never left.” In those days, folks were infatuated with Big Sky and enamored by the skiing experience they found: it was big, wide-open, with a sense of romance and freedom that reflected the essence of Montana itself. Even the tourists understood the spirit of the mountain; they were there to ski. And those who weren’t kept their footprint small and their attitudes in check. Locals ruled the roost, and skiing, not posturing, defined the culture.

As the years went by, things began to shift. More lifts, more frilly hotels, and more money poured into Big Sky. But the authentic skiing vibe still prevailed. Bob Allen, a local photographer who grew up in Bozeman, skied Big Sky for the first time in 1983. He speaks fondly of his first years at the resort, talking of cheerful ski memories and epic days on the mountain. The camaraderie was palpable, with lifelong friendships born of chairlift banter, rip-roaring descents, and carefree carousing at the Corral after a long day on the slopes. Allen recounts the times before long tram lines—before the tram was even installed: “In the early days, Lone Peak was hiking-access only, and it certainly felt like a real Montana adventure, offering endless opportunities.” Eager families from the Midwest drove for two days to soak in the solitude and epic skiing they lacked at home. For them, the resort’s ’90s-era advertising tagline rang true: “A Place All Your Own.”

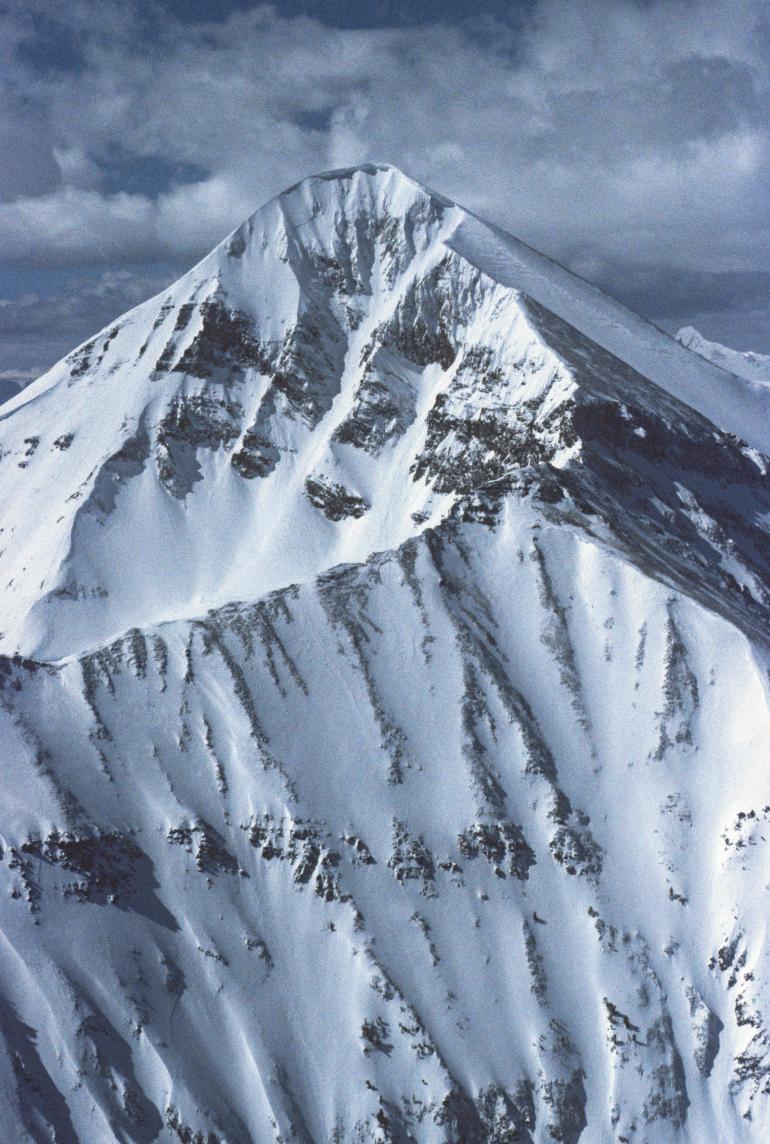

Within a few years, though, that slogan ceased to apply. “At the turn of the century, things seemed like they were ramping up,” Allen remembers. Increased development, new ski lifts, continued expansion, shady land deals, growing costs of lift tickets, and a developing town center—the focus began to change, and so did the resort. Real-estate moguls snatched up land, and the advent of the Yellowstone Club helped shift priorities, once and for all, to development and revenue potential. Left in the dust were all those who called Big Sky home, those for whom the mountain was not a motherlode of banknotes to be mined, but a source of recreation, restoration, and rejuvenation: an 11,000-foot temple that nourished both body and soul. That temple began to crumble amid the influx of people, changing mountain values, and consumerist nature of skiers on the mountain. And the Ikon pass didn’t help. “The adoption of mega-passes has also drastically changed many locals’ relationship with Big Sky,” Allen says. These passes invite more people, more buildings, and more wealth into the area.

But perhaps the most remarkable changes are in the town center. Sometime around 2010, the area became unrecognizable, seemingly overnight. The smattering of idiosyncratic, strip-mall-style cloisters, once the hubs of a charming little mountain town, became forgotten afterthoughts in the wake of gargantuan, monotonous, compartmentalized structures piled one on top of the other. Big Sky now fits the mold of every other tourist ski hub in the West. Commerce, not character, has become the prevailing ethos.

Many current Big Sky residents express concern about the pace and nature of growth in Big Sky. Without a municipal government, they feel the town is slipping further and further away from what it once was, with no regulation of development or curtailment of consumption. People of extremely elite status come and go, wheeling and dealing, skiing and skipping out, with no awareness of, or regard for, the health of the actual community. This increases housing prices and the cost of living to heights infeasible for those on local wages, pushing people out who aren’t in an upper tax bracket.

Commerce, not character, has become the prevailing ethos.

The once-beloved mountain now caters to upscale tastes far beyond most people’s reach. And these shifts are affecting local workers. Twenty years ago, there were plenty of jobs and places to live for people working in Big Sky. Now there are even more jobs available, but an ever-worsening housing crisis has left the market in shambles. Condos starting at a million dollars are not conducive to a genuine ski culture, nor do they offer cashiers, waiters, or retail employees anywhere to rest their heads after a long day’s work. The solution of the lodges and resorts, which need these service workers, is to buy up local properties and convert them to employee housing. Two-bunkbed dorm with a sewage-pond view, anyone?

Change is inevitable. And it would be naïve to discount the upsides of growth in small ski towns—it offers welcome revenue to locals, helps business owners, and generates flourishing job markets. Tangible benefits include easier fundraising for community centers, schools, and maintenance on trails and buildings.

However, in the case of Big Sky, the change has gotten out of hand, and the costs outweigh the benefits. The whole place is off-kilter. “It’s absurdly expensive up there,” says a Big Sky ski and bike instructor who commutes from Bozeman. Even if you are lucky enough to find housing, he adds, “You just hope the landlord doesn’t raise the rent more than you can afford. It’s extreme in Bozeman, but it’s insane in Big Sky.”

Undoubtedly, Big Sky is amazing—its terrain, scenery, and abundant wildlife are truly one of a kind. Developers and hospitality companies recognized this, capitalizing on the opportunity to get their share of the bounty. In short, Big Sky got found by the profiteers, and in the words of Bob Allen, “There’s no putting the genie back in the bottle.” We can’t reverse it; we probably can’t even change its course. But with the old Big Sky gone, as with Vail many years before, there is something we still can do: learn from it. We can recognize what we like and what we don’t like, in order to preserve other resorts and towns from a similar super-commercialized, under-regulated, unprotected fate. And yes, I’m talking about Bozeman and Bridger Bowl. If we don’t do something, and soon, we’ll be next.

For a look at O/B's timeline of Big Sky, click here.