Cruel Winter

A look back at harder times.

Winter in Montana is often sold as the season for outdoor recreation and cozy fireside evenings. But before all the ski lodges and outdoor shops hawking ice picks and puffers, winter in Montana was the most financially ruinous season of all, and it still demands respect.

On a single day in January of 1888, hundreds of people, many of them children, froze to death. The morning of the eleventh, a massive cold front swelled and swept southeastward from Alberta down into the Montana Territory, where it hit in the early hours of the twelfth, a Thursday, before stretching across the Great Plains all the way to the Midwest and as far south as Nebraska. Telegraph cables had been laid across the Hi-Line years before, but the dire weather warnings tapped on the wire that day could not outrun the storm that barreled across the badlands. It descended upon the country with such sudden ferocity that it caught by surprise many who had left their hearths and gone out to attend to chores, head into town, or walk to school. It came to be called the Schoolhouse Blizzard, the tenth deadliest in recorded history.

Countless souls have been allured by an idealized vision of the beauty of the West, and many times they’ve learned the hard way that beauty, especially that of the winter, can bear its teeth.

Nowadays, Montana draws in all walks from all over the map, many of them inspired by the near-propagandistic presentation of idyllic living in Big Sky country. And along with this rush of transplants looking for something new in Montana comes their own ways of seeing things; schlepping with them are not only their pasts, but their preconceptions, prospects, and politics. The old guard oft laments the loss of what used to be—the ranchers and farmers and longtime residents who invested in the state and its economy, worked the land, buried their dead in it. But there are parallels between those 19th-century honyockers who trundled across the continent in canvas-covered prairie schooners and their 21st-century out-of-stater parodies. Countless souls have been allured by an idealized vision of the beauty of the West, and many times they’ve learned the hard way that beauty, especially that of the winter, can bear its teeth.

Before the blizzards of the 1880s came, things had seemed opportune for settlers out on the “unclaimed lands” of the west. For nearly a decade, the prairies had filled up with families eager to make good on President Lincoln’s Homestead Act, which promised the deed to 160 acres pending their successful cultivation & improvement of the land for a period of five years. In the remote areas that now make up Montana and the Dakotas, thousands of pioneers built slatted homesteads and barns across the plains. Most of them had never experienced a winter west of the Missouri.

No one expected it that January morning. The day began unseasonably mild with temperatures above freezing, and few of the children who left for their classes wore heavy coats. By the time post offices and rail stops received news of the advancing front from the Weather Bureau, it was too late to be of any good. At Fort Keogh on the Tongue River, the mercury dropped 60 degrees in as many minutes. By noon, it was 30 below zero across half the Territory. Children were dismissed from one-room schoolhouses to wend their way home—often a walk of several miles in those days—only to be swallowed in the whiteout. All across the Dakotas and eastern Montana, they froze hunkered under haystacks, following fencelines home, disoriented in the bare and featureless wheat fields. And while the mortality rates of the Schoolhouse Blizzard in the Montana Territory are indeterminate, owing to its sparse & scattered uncounted population, some historians reckon as many as a thousand people died in total across the country. It was in Montana, on the Poplar River, that the coldest temperature was recorded during the tempest: south of minus-56 degrees Fahrenheit.

But it wasn’t the first time that Montanans had been hit hard by the snow. Only a year before, a brutal winter, the so-called “Big Die-Up”—a gallows-humor twist on the cowboy “roundup”—indelibly changed the economy and landscape of the land.

The cold killed an estimated 60 percent of all cattle in the Montana Territory, totaling somewhere around 362,000 head—the greatest single livestock die-off in American history.

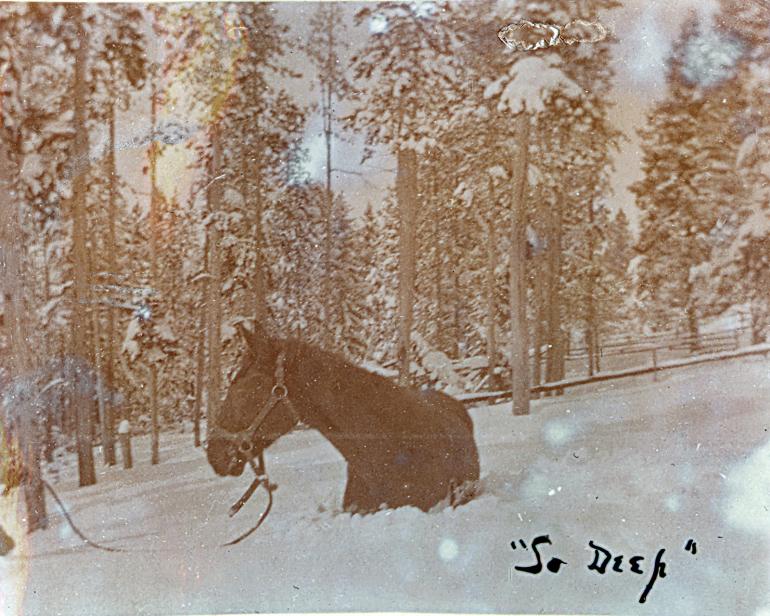

By the time the town of Bozeman was established in 1864, open-range cattle ranching was standard practice across the Montana Territory; cows wandered freely and fed with little to no upkeep, eating whatever they could find. Free-range grazing meant greater dividends for ranchers and their buyers on the western and eastern seaboards. But the new-world cattle that had displaced the native bison were ill-equipped for the frontier’s harsh environs. Unlike their ungulate cousins, cows would not hoof or bust through the crusted snowdrifts to uncover the grass beneath, nor did they have sufficiently insulating coats for extreme cold snaps.

When an exceptionally heavy snowstorm descended on the west in November of 1886, homesteaders stepped out of their cowsheds and stables into flurries so thick they could not see past three paces. Some became lost going out to the privy. The storm consistently hurled snow and wind across the prairie; cowboys desperately drove their herds in search of windbreak on the treeless plains.

The cold killed an estimated 60 percent of all cattle in the Montana Territory, totaling somewhere around 362,000 head—the greatest single livestock die-off in American history. Some ranchers lost ninety percent of their stock. By the time the Chinooks scoured the plains in March, the herds lay piled—bloating and crow-picked—in the muck. Granville Stuart, first president of the Montana Stockgrowers Association, remarked on the carnage at the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in Deer Lodge: “In the spring of 1887, the ranges presented a tragic aspect. Along the streams and in the coulees everywhere were strewn the carcasses of dead cattle. Those that were left alive were poor and ragged in appearance, weak and easily mired in the mud holes.” Hundreds of cattlemen went bankrupt. The Die-Up effectively ended open-range cattle ranching for good. Consequently, locals and coastal financiers realized that stockpiling hay for their herds would be the only way to get their animals through the winter. Every bale of hay across Big Sky country is a testament to the tragedy of 1887.

Even at the turn of the century, and well into the next, Montana remained a perilous place to wager on a rural livelihood. Electricity and gas heating were limited to a scant few population centers like Butte, Helena, and Great Falls. True, there were a few wealthier households and hotels in railroad towns that could afford to keep the lights on, but for most of the state, especially in the rural areas, Montana remained dark for decades. Out in the Gallatin, Paradise, and Shields valleys of southwestern Montana, the nights were lit by kerosene lamps and tallow candles, and the coal & wood stoves had to be stoked through the night during the long hibernal months. Not until the New Deal electrification initiatives of the ’30s and ’40s were electricity or gas heating even available for the majority, and there are still plenty living with memories of the frigid black nights that passed in the interim.

When the first automobile was registered in Montana in 1913, most townships still depended on the Northern Pacific Railway to deliver goods and necessities. Steam locomotives busted drifts with wedge plows, but oftentimes a rotary was needed to carve a corridor through the mountain passes clear from Butte to Livingston. Automobiles were a novel form of transport, impractical in the snow and dangerous during deep freezes. A breakdown far from home could be a death sentence. And while the Highway Act of 1921 made some progress in connecting rural areas to larger municipalities with access to medical care and whatnot, the great snows of 1919-20 marooned entire communities and rural homes for weeks on end. At the time, most journeys outside of town were made on horse or foot. (Incidentally, there are numerous stories of horses pulling ditched Model T’s out of the drift.) As for pedestrian travel, rubberized shoes were slow in coming; wool socks and stacked leather or wood-soled shoes had to be thawed and dried beside the fire or in the stove after a day’s tasks so they would be warm on the morrow.

In the spring of 1969, two and a half feet of snow fell in southeastern Montana in a single day, and drifts climbed high as telephone poles.

Of course, there were many other infamous winters in Montana over the last century that warrant recollection. The winter of 1935-36 kicked Montanans when they were already down from the Dust Bowl years, after droughts and wrecked harvests—then came the cold snaps, heavy snows, and ice jams. The storm winds that arrived with the new year visited upon the residents calamity the likes of which they had not seen since the 1800s, killing hundreds of cattle and horses and at least a dozen people.

In the spring of 1969, two and a half feet of snow fell in southeastern Montana in a single day, and drifts climbed high as telephone poles. The unexpected storm arrived precipitously during the calving season, and as before, nature claimed its share of the newborn. Houses and cars were buried. Heavy snowfall rendered Montana an iced-over archipelago of townships all cut off from each other.

More recently in 1989, Bozeman buckled under one of the state’s worst winters on record, the winter that everything froze. In February of that year, temperatures dropped to 50 below. Montana State University was forced to close. Pipes burst in the dormitories and the backup power system failed. Governor Stan Stephens declared a state of emergency. Windchill temperatures were deadly. Up north in Choteau, gusts were clocked at 125 miles per hour, leaving a wake of toppled trains, ripped rooftops, and four dead.

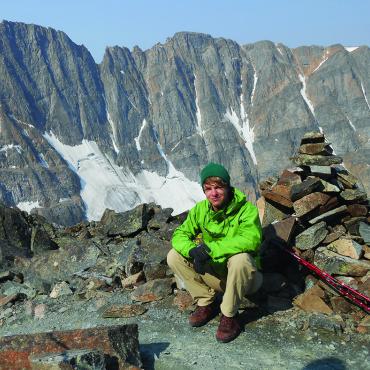

Nowadays, the months from November to April generate an enormous contribution to state coffers, drawing a coterie of powder hounds, Nordic skiers, and ice climbers every year. But before the lift lines and the groomed trails and the après ales, before the winters were commerce, they were a curse. And while it may sometimes seem that the worst of the frigid years came and went with the pioneers, resident Montanans have always—and continue to—faced severe winters now and again.

Not unlike the tourists who get thrown by buffalo in Yellowstone while they’re posing for selfies, plenty chechaquos don’t appreciate the adversities of the lean years braved by those who broke the sod before. Fictionalized, mythologized, often romanticized, life on the frontier was never a time to kick your feet up in a “lodge” out in the boondocks. The folk that came before—and they that live here still—aren’t going anywhere, and it’s because they know the land, its ways, and its vicissitudes.

The notion of an idyllic Montana winter was not born of comfort or leisure, but because of those hard and rugged souls who stuck it out, quite literally plowing the way so that the rest of us could play at surviving what they endured.

There are far fewer Montanans these days who remember what their predecessors lived through; far fewer who remember waking before dawn to smash ice off a frozen trough in the crackling dark; far fewer who recall the pang of losing a calf or a neighbor to a big freeze. There are far more who remember catered yurt hotels with Wi-Fi access, skiing vacations that cost a small fortune, and Christmas dinners in chalet getaways. There’s no sin in it, but the truth is plain enough: the notion of an idyllic Montana winter was not born of comfort or leisure, but because of those hard and rugged souls who stuck it out, quite literally plowing the way so that the rest of us could play at surviving what they endured.

Stacking cords of wood, building windbreaks, canning the summer’s yield, checking in on neighbors—these are all things that rural Montanans still do today, no different than their forebears near a century ago. But the world’s made easy now, and winters have become fodder for influencers and pleasure-seekers. The modern luxuries we take for granted, even the simplest, whether indoor plumbing, heated automobiles, or instant communication—all these technologies have insured us to a pleasant and comfortable relation with the long brumal nights.

But when the power dies, and the internet goes out, and the house grows cold, and the drifts climb the walls, creaturely frailty creeps in with the draft. In those sublime moments of powerlessness, when we lose our presumptive control over the elements, we are ruefully reminded that human beings haven’t existed on this planet all that long, and that the winter is still an untamable thing.