Risk & Reward

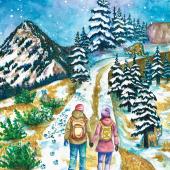

A gift of solitude in the mountains.

“There is a time in every man’s education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better, for worse, as his portion… The power which resides in him is new in nature, and none but he knows what that is which he can do, nor does he know until he has tried.” ― Ralph Waldo Emerson

Wandering through the woods toward Blue Lake (a day late because of a large misadventure), I met a man from a middle-of-nowhere town called Ironwood, Michigan—ironically the same place my brother lived for years. We chatted a while, like two good Midwesterners, and when we parted at the lake, he seemed very concerned that I was at it alone. Others had expressed similar feelings before I’d set out. But to me, the danger and risk of being alone brought heightened focus, and greater trust and reliance on my own decisions. So I didn’t let his uneasiness deter me. After all, the day was flawless: bluebird skies and air so still you could almost hear the dew evaporating.

I moved higher, and was struck by the beauty of the sun rising across the canyon in complete stillness—no wind or voices to disturb the rays on their journey to the ground. The silence was so deep that I could feel it wash over the residual ringing in my ears left by a hectic week. The silence softened and eroded that sound, just like water did to the soil in the marshland under my feet. I discovered one of the greatest gifts of solitude: space to think.

I began to climb up the pillar too far left and realized my mistake too late. I continued anyway, the only thought in my mind being the necessity of reaching the top. There was no discussion, no panicked conversation; just move up.

After a short break for water and time to take in the view, I transitioned from the spongey wetland to the slow work of scrambling up loose rocks, snow, and ice toward the ridge. Crazy Peak is by no means an unattainable or exceptionally risky climb, and yet, my adrenaline rose with the altitude. I knew there was no one around if I fell or triggered a rockslide. I was on my own. The climb to the ridgeline felt never-ending. Each step was precarious, and I could hear the deep tones and feel the subtle shifts in the scree. But the only way forward was up, and one step after another, I eventually crested the ridgeline and got a breathtaking view of black mountains, green valleys, and ice-blue glacial lakes.

Relieved to have finished the terrifying scramble, I made my way across the ridge. I felt I had come a long way, but knew that the most threatening part was ahead: an 80-foot downclimb. All other thoughts ceased as I climbed down and stopped on a small ledge to admire a looming couloir I had come upon, its size augmenting how small I felt. I continued on around a second pillar just before the final scramble to the top.

I began to climb up the pillar too far left and realized my mistake too late. I continued anyway, the only thought in my mind being the necessity of reaching the top. There was no discussion, no panicked conversation; just move up. I rolled over on top, again realizing that if I had fallen, there would have been nothing stopping my plunge—a risk analyzed before and reflected on after, but certainly not contemplated during. Allowing danger close is one fool-proof way to force oneself to be entirely and completely grounded, thinking only of exactly the present, an art that loses footing in a more comfort-driven environment.

Sitting on top, knowing that my trip was only halfway over, I still felt a sense of accomplishment—the doubts of others had not discouraged me, my own mistakes hadn’t forced me to give up.

Sitting on top, knowing that my trip was only halfway over, I still felt a sense of accomplishment—the doubts of others had not discouraged me, my own mistakes hadn’t forced me to give up. I was learning that you don’t always need a spotter or someone there to catch you if you fall. Sometimes the threat of the fall focuses your concentration, actually increasing safety. It also accentuates the beauty of a place all the more. I watched birds circle, riding on the currents of the wind. It was a flawless day and without the distraction of companionship, I didn’t miss one bit of it. The deep blue of the sky above faded into a lighter blue until it hit the horizon with a dash of orange and the faint white of distant clouds. After a while, enjoying the view before me and the feeling of being small and insignificant, I made my way down.

I was on edge because of the shifty ground, but I knew the base would come eventually. Then I quit thinking; there was nothing else to think. It just was. And eventually I did reach the base of the immense wall. This time, though, sunlight permeated every corner of the canyon. The peat-like ground underfoot felt smoother than water, in contrast to the hard rocky terrain I had just stepped from. I reveled in a journey that was all mine; no one else saw that view with the sun at that angle, at that time, on that day. I reached the lake and realized that in all the excitement and methodical climbing, it had been hours since I’d eaten anything. So, I found a place in the sun, took my shoes off, let the water run over my feet, felt the sun on my face, and ate peanut butter. Because what else would you ever eat in the mountains?