Written in Snow

Pondering the fleeting mysteries of nature.

November clouds ripe with winter had settled solidly over the Beartooths, showing no intention of departing until May. Yet the stubblefields of the Stillwater Valley held little snow. Flocks of geese sat amid the remnant grain, alternating between eating and warily scanning the southern skyline, as if assessing the difficult 12,000-foot climb ahead. Deer grazed along paddock edges, keeping close to the safety of creek bottoms and willow thickets. Although no ice had formed on the Stillwater, the water already ran with the slow, inky blackness of a winter river.

A coyote, its fur thick and clean, trotted along the road, carrying a dead partridge in its mouth. When a car approached and slowed, the coyote broke into a lope toward the river. The coyote threw two cautious glances over its shoulder before pausing at the edge of the cottonwoods to watch a couple step out from their car. For a moment, the three watched each other, all minds focused on the meaning of the partridge, until the coyote turned again and disappeared into the trees.

The people returned to the car, rubbing their goose-bumped arms. They drove on, leaving the Stillwater to follow the Rosebud. Miles later, high in the foothills, ice crept along the river’s edge. They left the Rosebud Valley at Roscoe, where the road turned east toward Red Lodge. The country they crossed—all soft, rolling hills—looked golden, raw, and prime for winter. Few cars passed. Fewer homes displayed the telltale chimney smoke that signaled holiday gatherings. With little snow on Red Lodge Mountain this year, many Thanksgiving feasts would be held in the Yellowstone Valley—much as the Crow had moved to the warmer lowlands in winter.

The country they crossed—all soft, rolling hills—looked golden, raw, and prime for winter. Few cars passed. Fewer homes displayed the telltale chimney smoke that signaled holiday gatherings.

Red Lodge, indeed, felt empty. The couple took a room, then walked through the quiet town as night fell. The breeze brought a damp chill, heightened by snowfall that melted as it hit the ground. Christmas lights reflected off the wetness on Main Street.

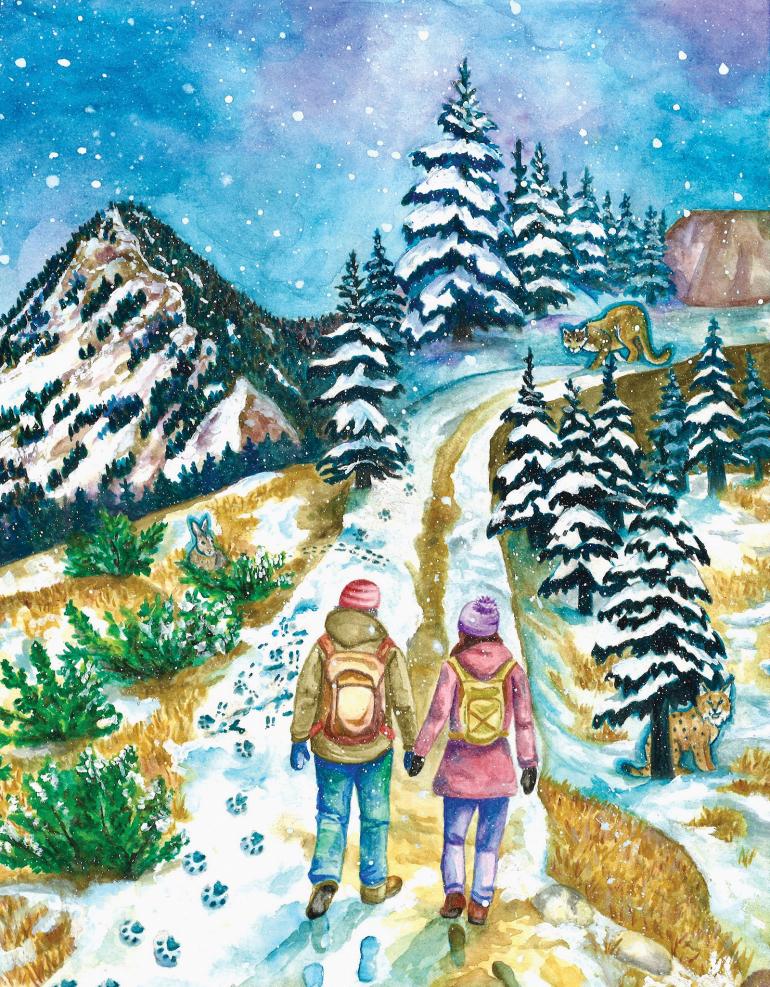

On Thanksgiving morning, dark clouds continued to hover over the Beartooths. The couple strained to see through their frosted windshield as they drove into the mountains. While blocks and folds of ice covered much of Rock Creek, cascades and rough water ran clear and open. Snow showed only in the shadows of trees and sagebrush. The couple left their ski gear in the car, opting instead for worn hiking boots and daypacks. With no children, their yearly celebration of thanks came not with joyful voices marveling at giant floats on TV, but with the grace of good, wild country.

The trail led to Silver Run Plateau, named during the unsuccessful mineral exploration efforts of the first half of the 20th century. The true riches were in the quiet of the forest, and the beauty of the deep-cut canyons. The 3,000-foot elevation gain along Rock Creek to the plateau promised to be a cold hike, but as the couple moved up the trail, they shed their gloves and coats. The pale sun warmed the trail on the open hillside.

They climbed steadily, intermittently through forest, rounding switchbacks until the car below seemed distant and detached. A thousand feet up, new snow began to show, slipping from the pines and scattering over their hot faces like a fine mist. Three inches had fallen the preceding evening. In the forest, snow covered previously bare trail, though the open areas remained clear. The snow squeaked pleasantly underfoot like the white sands of a North Queensland beach, holding the imprint of a boot perfectly.

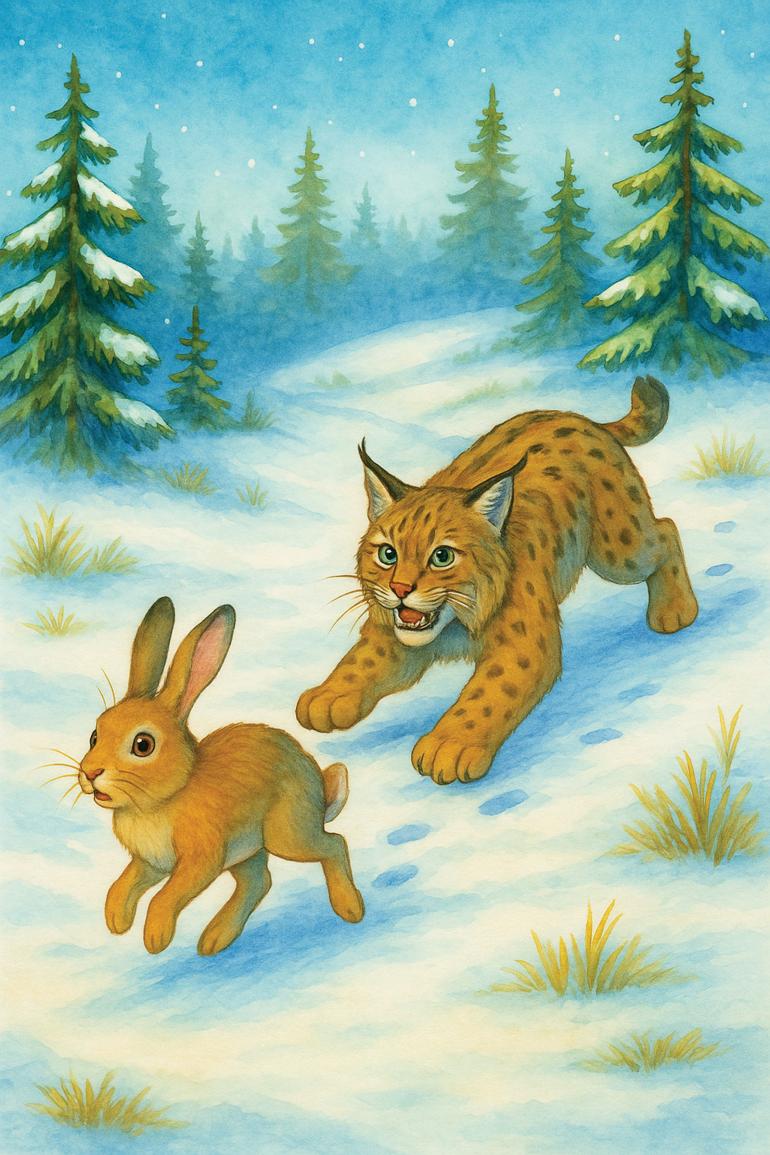

Surveying the scene, the couple could almost see the fear in the hare’s eye as it realized its peril, hear the cat’s screech in the fight, and smell the blood of the kill.

Just past the intersection of the trail and a stream, a delicate set of bobcat tracks emerged, each toe pad discernable. The tracks descended the mountain, equidistant and unhurried. Fifty yards up, the snow broke in a roughshod, chaotic tumble of bare dirt, jumbled tracks, body imprints, and scratched earth. Above it sat four feet of unbroken snow, interrupted only by two sets of hurried tracks and divots clawed into fresh dirt and snow scattered from the trail—a clear sign of a frenzied tussle.

To the left and down into the trees, the even, unbroken path of a snowshoe hare led directly into the area of the first scuffle. Fifteen feet higher, the hiking trail slipped over a small knoll, and doubled back on itself. Bobcat tracks, as even and unhurried as those before, rounded the switchback. Just before the knoll, however, they changed from meandering to tightly spaced and taught. Next came a rectangular pattern of four deep marks in the snow, with a shallow chest imprint in its center. From there only three bounding track sets showed in the 15 feet between the crouch and the first encounter.

Surveying the scene, the couple could almost see the fear in the hare’s eye as it realized its peril, hear the cat’s screech in the fight, and smell the blood of the kill. They walked back and forth, careful not to trample the story unfolding before them.

“This must have happened today,” the women said, wide-eyed.

Time and time again, they pointed to scenes in the battle: the approach of the unsuspecting quarry; the bobcat’s stalk; the place it hid below the knoll; the bounding charge; the initial battle; the escape and second terrifying entanglement. But then they noticed something else—the absence of blood and fur. A closer inspection showed another surprising detail: hare tracks fleeing the lower scuffle area, heading pell-mell down into the forest. No bobcat tracks followed. Instead, the unsuccessful cat had departed down the trail, through continuous snow, before peeling off and heading downslope.

The couple walked on, enthralled. They rounded the switchback and began to climb. Out of the woods, little snow held on the trail and the bobcat’s tracks disappeared in the dirt. But a few steps later, the couple reentered the forest above the skirmishes. Continuous snow covered the trail again. Continuous, that is, except for the tracks of another cat. Like the bobcat’s, these tracks showed the perfect imprints of each pad, with no claws evident. But they were easily three or four times as large as those of the bobcat.

They realized witnessing the stories the tracks tell demands but a single requirement: to be present, both in body and in spirit.

“Mountain lion,” the man whispered. The couple stood up and looked into the forest.

The tracks were moving downhill. The couple continued up, walking along the trail’s edge to avoid destroying the story of the lion’s passage. Intermittently, a long, snake-like swoosh marked the snow between the tracks.

“Its tail,” the man said quietly, pointing and smiling.

“That is so cool!” the woman whispered back.

The couple walked for 15 more minutes, rounding several more switchbacks. The trail frequently turned bare on exposed hillsides. But when the snow returned, the lion’s unhurried tracks were always there, showing that it had followed the trail down much of the mountain. Finally, on a switchback in the trees, the tracks broke away from the trail, climbing toward a rock outcrop that showed through broken forest.

They pushed on up the trail, snow—new and old—deepening as they climbed. Wind howled along a ridgetop above the Lake Fork, freezing their sweat, but the trail quickly ducked into the safety of the forest again. Hours along, and the couple passed through calf-deep snow.

Finally, they broke out of the forest onto a rocky knob, buffeted by an icy wind. The Silver Run Plateau stood before them, looking as cold, barren, and empty as the Arctic tundra. Deep creeks cut wedges in the flat table of the plateau, starting with rock gardens before gathering dense forests as they dropped to the Rock Creek Valley. No animals stirred on the open expanse. The only movements came from snow racing across the plateau, paralleled by cold, fast-moving clouds 500 feet overhead.

The frigid wind soon drove the couple off the knob. Back in the forest, and heading back along the trail, their thoughts returned to the tracks farther down the mountain. Could the mountain lion have interrupted the battle between the bobcat and the hare? No lion tracks appeared at the point of the struggle, but they last showed a short distance above, with a clear view of the skirmish sites below. Is it possible that the bobcat and the hare, in the heat of battle, would even have noticed an approaching lion? Could the lion have inadvertently saved the hare? Had it interrupted the battle, only to pursue the hare itself? If it had, where did the lion tracks go? And the seemingly unperturbed steps of the bobcat below the second skirmish… upon the appearance of the lion, wouldn’t the bobcat have run for its life? No, perhaps the lion had come along later in the morning, just after the hunt, but just before the couple. Perhaps the approaching lion—a single switchback above—had slipped silently into the forest while the couple marveled over the story of the tracks.

The couple would look, they decided, for more clues when they returned to scene.

An hour down the trail they shed additional layers, warmed by the hike, the still air, and the increasing sun. Soon even their mid-layers had been tucked into the packs. As they lost elevation, the trees began to shed snow in clumps. Droplets slipped from pine needles and splattered on rotten logs. Small rivulets formed in the trail.

Tracks, like all of life, are transient, ephemeral, short-lived. The story of the hare’s escape existed for only a few fleeting heartbeats.

Farther down still, the trail squished underfoot. The soft, fresh snow of the morning had turned to wet slush. It was now more translucent than white. They passed the switchback where the lion had first emerged onto the trail. Its tracks were now thin, almost indecipherable, in the diminishing snow. In places, the trail showed like a photographic negative: the toepads had completely melted into the dirt track, and the gaps between the pads showed as remnant ridges in the slush. The swooshing tail marks were gone.

By the time the couple reached the final switchback above the hunt, the mountain-lion tracks had disappeared. Stretches of the trail ran wet and muddy. The knoll above the battle of the bobcat and the hare revealed no sign of the stealthy hunt, no sign of the pounce. The scraped dirt still signaled two encounters, yet told so much less without the presence of tracks.

The couple walked on, unable to build on the story they had already witnessed and mentally embellished. Below the second skirmish, the trail gave no hint of the bobcat’s passing that morning.

Crossing the small trickle where they’d first spotted the bobcat tracks, the couple met a second couple coming up the trail, fresh with excitement over their afternoon hike. The four greeted each other with a “Happy Thanksgiving,” and then remarked on the warm November sun. Soon the other hikers departed.

Stretches of the trail ran wet and muddy. The knoll above the battle of the bobcat and the hare revealed no sign of the stealthy hunt, no sign of the pounce.

The couple started out again. A few steps on the man said, “They’ll never know about the bobcat and the hare, or the mountain lion.” The woman looked back, nodding in thoughtful agreement.

They walked on silently, thankfully. In that moment, both of them realized they would be the only people on Earth who would witness the story of the tracks. Tracks, like all of life, are transient, ephemeral, short-lived. The story of the hare’s escape existed for only a few fleeting heartbeats. To witness the stories tracks tell, they realized, demands but a single requirement: to be present, both in body and in spirit.

Then they realized that the story was not for them, but rather held significance in and of itself, speaking to the value of wild country and of creatures free to live out age-old patterns. While the couple knew their discovery had been one of luck, they viewed it more importantly as one of privilege, one worthy of true thanksgiving.