The Celestial Outhouse

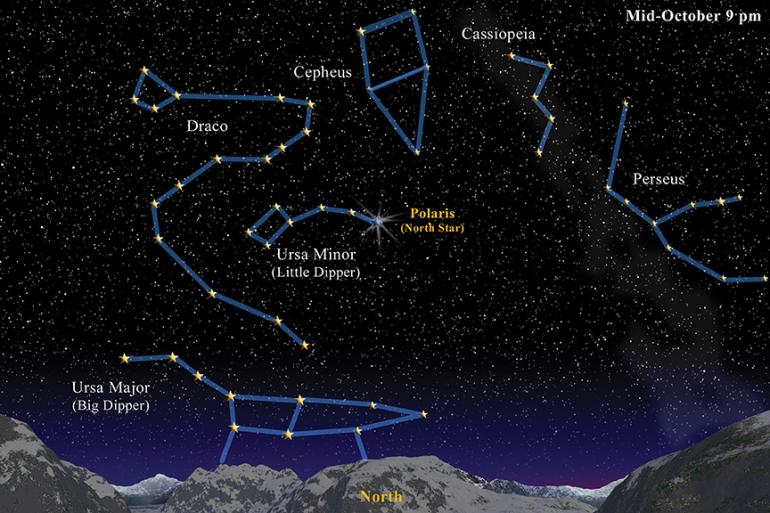

Fall's starry sky.

The storied Western homestead, out on the windswept prairie or tucked into a rocky canyon, might variously have corrals, barns, or sheds clustered about the ranch house. But the one outbuilding—always “out back”—that one could count on seeing was the peaked-roof “outhouse,” to use the vernacular. Westerners were, after all, a practical people.

The sky’s a pretty practical place, too, and if you look hard, you can find one of these accouterments to daily living in the sky as well, right alongside the North Star for everyone to see—if you know where to look.

The Celestial Outhouse can be challenging to find (never a good thing for those in need of one), but it helps to start with the Big Dipper, swinging low in the north on fall evenings. Follow the Pointers (the two stars of the bowl farthest from the handle) up to the North Star (Polaris) and trace a little beyond, and you’ll pass by a star that’s about one magnitude (two-and-a-half times) fainter than Polaris. This is the star that marks the peak of the outhouse roof, the similarly bright four stars outlining the building stretched out beyond. (To the right-hand side of the outhouse lies the brighter “W” pattern of Cassiopeia, as a check.)

The Greeks gussied up this pattern by making the “throne” a royal one—for this constellation is more politely known as that of Cepheus the king. There are two Cepheuses in Greek mythology—one sailed with Jason as an Argonaut in search of the Golden Fleece, fathered numerous children, and died gloriously in battle. That’s not this guy. This guy had just one child and his family got him into lots of trouble.

The Cepheus of the sky was king of legendary Ethiopia (not the current country, but a stretch of coastline along the Mediterranean), and married to the aforementioned Cassiopiea. The queen was as vain as she was beautiful, and boasted that she was more ravishing than the nymphs of the sea. This got back to the nymphs, who were not amused, and they tattled to their father Poseidon, god of the sea, who was not amused either. He ravaged Ethiopia’s coast, ultimately demanding the sacrifice of the couple’s only child, the princess Andromeda, to the sea monster Cetus whom he would send to snack on the hapless girl.

Andromeda was shackled to a rock by the sea to await her fate, but who should come along at just the right moment, as Cetus rose from the waves smacking his monster lips, then the timely hero Perseus. Some versions of the story have him arriving via winged sandals, others on the back of Pegasus the flying horse, but arrive he did, fresh from his slaying of the Gorgon Medusa, whose snake-haired stare turned living creatures into stone. Perseus popped her severed head out of his satchel, displayed it before Cetus who obligingly turned instantly into rock, and freed Andromeda as Cetus sank, well, like a stone. Of course they were married and lived happily ever after mostly, but Cepheus and his wife did not fare quite so well.

All of the major players in the story—Cepheus, Cassiopeia, Andromeda, Perseus, Cetus, and the sometimes-appearing Pegasus—are splayed across the north and east of the sky on autumn evenings. But the king and queen have the dubious honor of circling the Pole Star, which means they spend half their time upside down, the blood rushing to their royal heads. And Cepheus has the additional fate of being shaped rather like another sort of head from the days of the rural West, as he sits upon his throne and wonders how he got there.

Jim Manning, formerly the executive director of the Astronomical Society for the Pacific in San Francisco, lived outside Bozeman for many years and visits regularly.