Easy Livin'

Lassoing the summer sun.

Summertime… the season when the livin’ is easy, according to Clara in Porgy and Bess, who sang the famous song to her baby in the George Gershwin opera. I’ll grant her that the fish may be jumpin’ now even in Montana, but the high cotton in her lyrics is nonexistent at this latitude—though the winter wheat should be doing nicely.

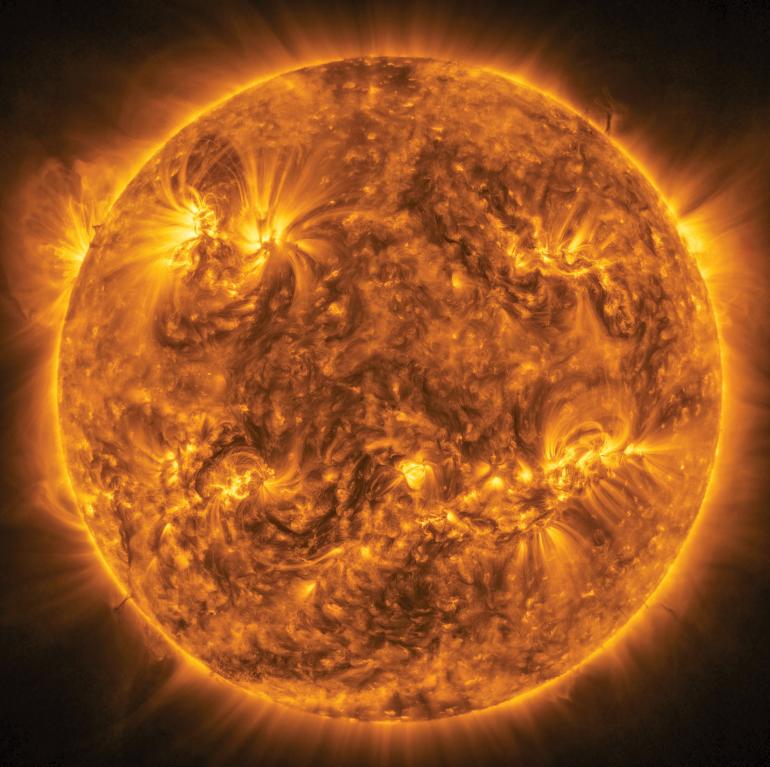

What is high now is the sun, its brilliant, desiccating orb shining down on our semi-arid landscape from a maximum altitude of 68 degrees at solar noon in Bozeman on the June 20 solstice, just 22 degrees south of overhead. It will maintain a midday maximum altitude of more than 60 degrees through July and into early August as its daily arc across the sky slowly loses height as summer passes.

No matter how busy your summer may be, take a cue from Maui and lasso some time to slow down and enjoy the long, lazy days while the sun rides high.

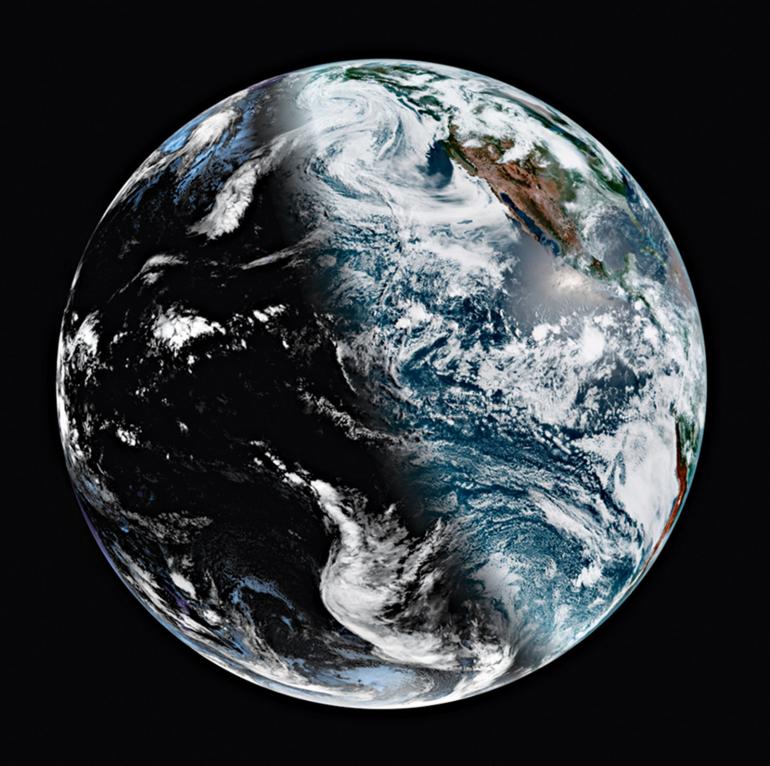

And yet, early summer is the time when the Earth is actually farthest from our star. This year, our planet reaches aphelion—the farthest point from the sun in its slightly elliptical orbit—around 2pm on July 3, just as we’re buying our civilian (and presumed legal) fireworks for the Fourth. Earth will then be 94.5 million miles from the sun, about 1.5 million miles farther than the average of 93 million miles. (It was at perihelion—its closest to the sun—last January 4, just as we kicked the Christmas tree to the curb and settled in for winter. At that time, we were 91.4 million miles from the sun, about 1.6 million miles closer than average.)

This may seem confounding, but the difference in distance is negligible compared to a much bigger effect in the politics of the seasons: tilt. Not right or left, but toward and away.

Our planet is tilted 23.5 degrees from vertical with respect to its orbit around the sun, which means that on one side of Earth’s orbit, the northern hemisphere will be tilted 23.5 degrees toward the sun (marking our summer solstice), and on the opposite side, it will be tilted away (marking our winter solstice). When our hemisphere is tilted toward it, the sun rides high in the sky during the day. It shines down more directly, heats our hemisphere more efficiently, and produces the easy-livin’, fish-jumpin’, high-cotton summertime Clara sings about. When we’re tilted away and the sun rides low across the sky, it heats us less efficiently, we cool off, and we get winter. (The southern hemisphere, whose tilt is opposite to ours, has opposite seasons.)

Earlier cultures came up with their own ideas about the sun’s behavior and effects. We may take summertime heat for granted these days, but Native American folklore tells a story of a time when an endless winter buried the land and its animal occupants in snow. Raven, who back then had rainbow-colored feathers and (like Clara) a good voice, agreed to fly up to the abode of Creator to ask for fire from the sun. He sang so sweetly that Creator poked a stick into the hot sun and gave it to Raven as a gift, and Raven flew back down to Earth with the burning brand. The animals used the fire to melt the snow and warm up—but on the journey back to Earth, it burned Raven’s feathers black and the smoke hoarsened his voice, giving us the raven we know today.

In Polynesian myth, summers didn’t used to be so lazy, because the sun traveled too quickly across the sky and the days were short. So the folk hero Maui fashioned fiber ropes and lassoed the sun, making it promise to travel more slowly before he let it go. It’s said that sunbeams shining through clouds in the morning or evening are Maui’s ropes still dangling from the sun.

No matter how busy your summer may be, take a cue from Maui and lasso some time to slow down and enjoy the long, lazy days while the sun rides high. All too soon we’ll be buried again in snow and looking for where Raven stashed his fiery stick.

Jim Manning is the former executive director of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. He lives in Bozeman.