Tree Talk

How to identify different trees in southwest Montana.

“Learn character from trees, values from roots, and change from leaves.” —Tasneem Hameed

We Montanans are lucky. While lots of other folks peer out their windows at concrete and steel, we’re surrounded by nature’s skyscrapers—trees. We string up hammocks between them, ski lines through them, lean against them on summer hikes, and rely on them for color, cover, and clean air. They’re playgrounds for mountain lions, scratching posts for bears, and crucial homes for birds, bugs, and just about everything in between. But how well do we really know our woody neighbors? Let’s break it down.

DECIDUOUS TREES

These are your leaf-droppers. They shut things down for winter, dropping broad leaves to conserve water and survive the cold months. Most live 50 to 500 years, depending on the species—and they put on one heck of a show come fall.

Quaking Aspen

Found between 4,500 and 10,000 feet, aspens thrive on moist mountain slopes and in valley bottoms. They’re known for their white bark, fluttering leaves, and golden fall colors. Aspens grow fast and spread via root suckers, forming massive clonal groves (a whole stand might technically be one tree). Fire suppression—or more precisely, a lack of small, natural fires—and hungry elk are their biggest threats.

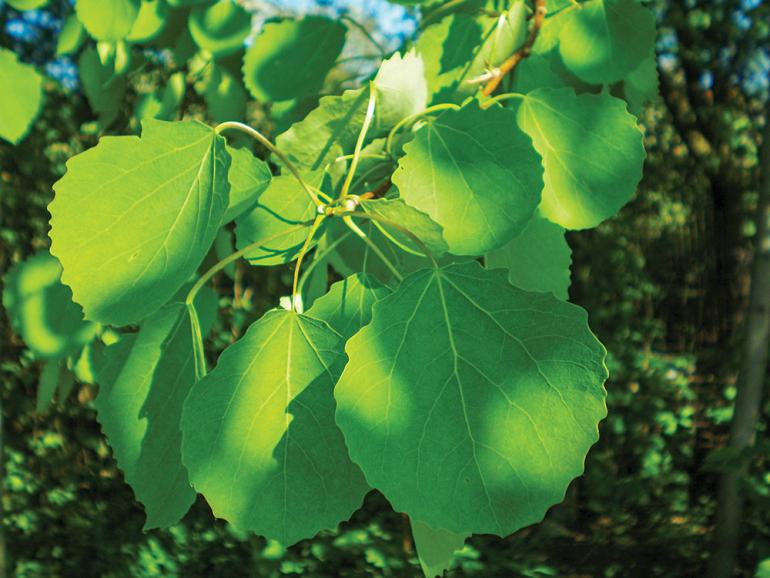

Cottonwoods (Black & Plains)

Montana’s riverside giants. You’ll spot them in riparian zones along rivers and floodplains. These towering trees stabilize banks and give beavers, eagles, and other birds plenty of shelter. Look for broad leaves and deeply furrowed bark. Their fluffy seeds ride the wind, but need exposed, wet soil to take root—usually post-flood. Habitat loss, invasive species, and wildfires threaten these trees.

Rocky Mountain Maple

A relative of the more famous sugar maple, this species grows in shady spots along streams and canyons, usually between 5,000 and 12,000 feet. These shrubs or small trees have simple lobed leaves and red stems. They’re loved by elk and deer for food and cover, and like other deciduous trees, fire suppression and drought aren’t doing them any favors.

EVERGREEN TREES

Unlike their deciduous cousins, evergreens keep their foliage year-round. Most are conifers: needle-bearing, cone-producing, cold-hardy champions of the high country and dry slopes.

Douglas Fir

Don’t let the name fool you—it’s not a true fir. These trees are all over Montana, thriving from valley bottoms up to 7,500 feet in southern parts of the state. Key ID features include soft, sweet-smelling needles, thick bark, and cones with three-pointed bracts (a.k.a., “mouse tails”). The trees are fire-tolerant and common in mixed conifer forests.

Lodgepole Pine

The comeback kid after fire. Lodgepoles grow tall and narrow, often in dense stands. Their needles come in pairs, and their cones only open with heat—making them the poster child for fire adaptation. They’re found at higher elevations, especially in areas where fire has swept through in the past.

Ponderosa Pine

Poderosas are the scent of summer hikes, and are Montana’s state tree. They’re found lower in elevation (3,500-5,500 feet), often on dry, south-facing hills. Their needles grow in bundles of three. Mature trees have thick, orange bark that smells vaguely of vanilla. Their deep roots and thick bark help them shrug off fire.

WHITEBARK VS. LIMBER PINES

These two pine species are icons of the Greater Yellowstone landscape, but they can be challenging to tell apart thanks to their similar statures, coloration, and needle patterns. Pay close attention to their cones (and their elevation), though, and you might be able to tell them apart.

Whitebark

Whitebark pines are the endangered symbol of the high alpine. These twisted, gnarled trees feed grizzlies and birds alike, and their seeds are tucked away by Clark’s nutcrackers, helping regenerate forests. They’re relatively short, often with multiple trunks growing in a single clump. Unfortunately, the trees are threatened by blister rust, beetles, and climate change. Over 50 percent of whitebark forests have already died off in some areas.

Limber

Flexible, drought-tolerant, and found from valley to summit, limber pines have soft, five-needle clusters and a gray bark. Like whitebarks, they rely on birds to spread their seeds. Old-timers over a thousand years old still stand in places like the Beartooths and the Gallatin Range. They stabilize soil on rocky slopes and outcompete just about anything else in harsh conditions.

Key Differences

During the growing season, whitebark cones are roundish, purplish, and point upward. Limber cones are longer, green, and hang down. Elevation’s a clue, too—whitebarks tend to live higher up.

Next time you’re out wandering Montana’s woods, take a closer look. Those trees aren’t just background scenery—they’re locals, too. Ancient, resilient, quiet locals—the best kind.