Mars Returns

The red planet lives.

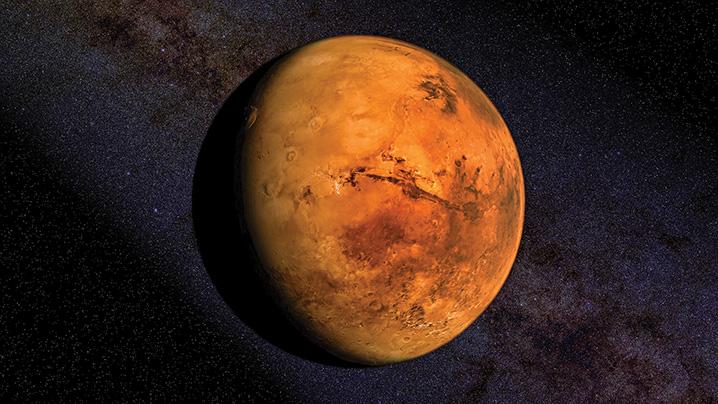

It’s the color. Lurid, baleful red, blazing unblinking in the night sky. Like a burning ember, or a drop of blood. No wonder this “wandering star” in the realm of the gods was associated with grisly characters.

And now it’s back, as it is every two years and two months, shining brightly in the autumn evening sky. Mars returns!

Not as if it wasn’t up there the whole time, but Planet Mars is usually dim and undistinguished because it’s small and far as the planets whirl about the sun. But every two years and two months, our speedier Earth passes the Red Planet in its more distant orbit. That means we’re much closer to it, making Mars look bigger in telescopes and very bright in the sky.

On October 13, the planet lies at “opposition,” opposite the sun in our sky as Earth slips between the two. Mars rises at sunset and is in the sky all night, unmistakable as a brilliant, red untwinkling light in the south among the stars of fall. Thereafter, it’s already in the sky at sunset and will dominate the night through the autumn, briefly outshining everything in the night sky except the moon and Venus.

The planet shines brighter this year than during most oppositions because Mars is just a little past perihelion (its closest point to the sun), so it’s also a little closer to us as well—about 38.5 million miles away. It’s also higher in the sky than it was last opposition in 2018, when a global dust storm obscured all of its telescopic features. If Mars avoids a dust-up this time, it should show some dark features through a good telescope and perhaps a shrinking south polar cap in the midst of southern-hemisphere summer there.

Today we see in the rusty planet a sibling world. But in ages past, when the shifting planets were pegged to gods, the Sumerians attached the Red Planet to Nergal, their deity of war, destruction, and pestilence. The Greeks associated it with Ares, likewise a savage and generally unsavory god of warfare. The Roman counterpart was Mars, though the militaristic empire rehabilitated his reputation a bit and made him guardian of Rome, a strong and somewhat fatherly figure who gardened on the side. March was named for him, and of course, the planet.

For all our modern regard, the rusty world can’t quite escape its notorious past. Once telescopes began studying the planet and found it to be the most Earth-like in appearance, we populated it with a dying, thirsty, warlike race jealous of watery Earth. H.G. Wells had the Martians invade us at the very end of the 19th century in his novel The War of the Worlds, when our bacterial forces infected them and won the day. Science fiction, radio, TV, and movies have carried on this tradition ever since. In point of fact, we’ve become the invaders by hurling various spacecraft its way.

Periods of opposition, when we’re passing Mars, are the best and most efficient times to launch spacecraft to the Red Planet, and this year, an entire fleet is going. At the end of July, United Arab Emirates launched an orbiter; China an orbiter, lander and rover; and the US a rover as well. The American Perseverance, if it lands successfully next February, will deploy a small reconnoitering helicopter, search for evidence of ancient microbial life, and cache soil samples for future return to Earth.

But always, it’s the color that draws us—like a burning coal from a mountain campfire against the chill of an autumn night. Rusty, mysterious, possibly a cradle of simple life in its wetter and warmer youth, it waits for us and for our emissaries, lurid and luring all at once. So bundle up as the leaves turn ruddy, and go out and find the ruddy planet in the night sky. Mars returns!