She’s a Butte

Developing an urban trail system on Montana’s richest hill.

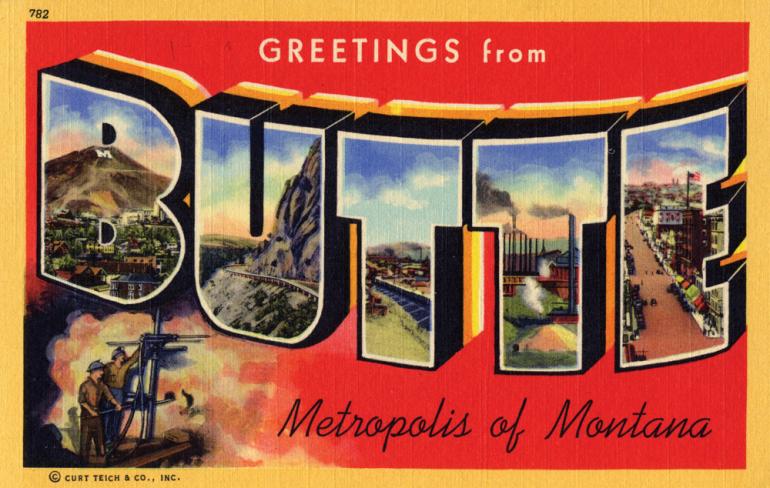

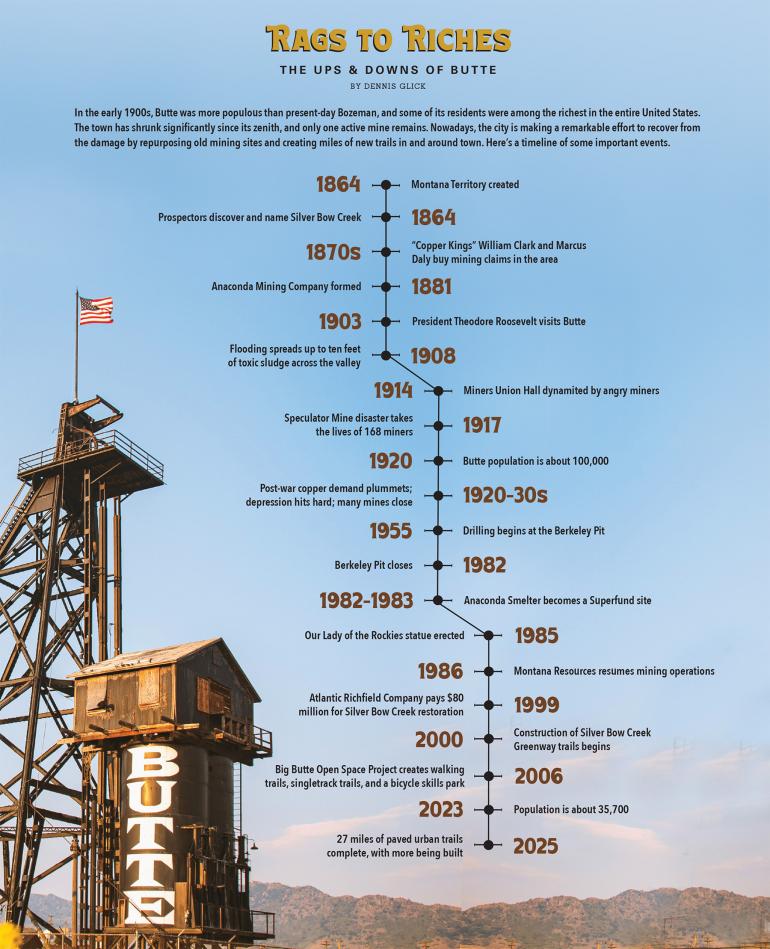

It wasn’t long ago that when Butte came up in conversation, common catchphrases included less-than-flattering words such as, “Berkely Pit,” “superfund,” and “shuttered storefronts.” And of course, Evel Knievel would be mentioned—sometimes as a positive influence, but oftentimes not so much. Today, however, reactions to mention of the Mining City might still include, “Berkely Pit,” but they are more apt to focus on accolades like, “Montana Folk Festival,” stirring history, cool neighborhoods,” and, of course, “Touchdown Tommy Melott.” And if you lived in, or spent time in Butte, you might very well add, “awesome trails” to that list. This is the remarkable story of Butte’s recovery from polluted mining town to a trail-lover’s haven.

Back to the Future

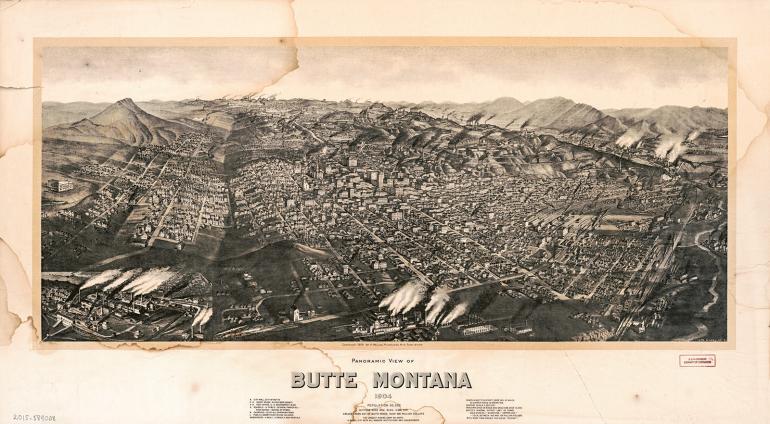

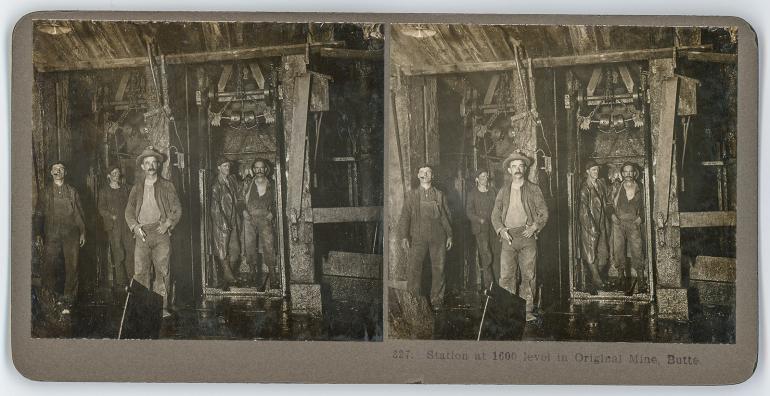

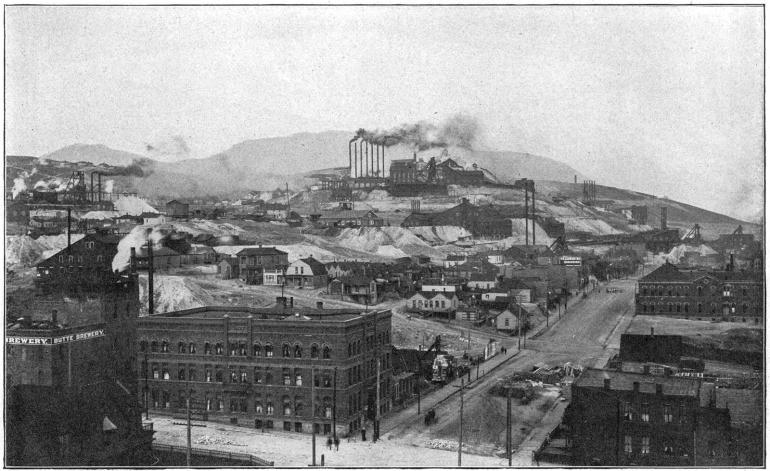

Through an interesting set of circumstances—which, as per usual, involved a partner moving for a job—I found myself living in Butte in the early 1980s. Mining had all but ceased (though some open-pit mining did resume in 1986), the city was depopulating, and historic buildings were burning on a regular basis. There was even talk of knocking down the iconic headframes that had once lowered copper miners as deep as a mile underground.

At that time, I was (and still am) an outspoken advocate for wilderness and wildlife. Suddenly finding myself in the middle of one of the most environmentally degraded landscapes in the West, I felt marooned. But not for long.

I soon realized that if there was such a thing as an “industrial wilderness,” this was it. Being a lover of history, it sunk in that I was in the epicenter of one of the most historic places on the planet—at least when it came to industrial history. Falling in with a cadre of historic-preservation aficionados furthered that realization.

Yes, mining had wrought unimaginable ecological destruction and had untold effects on human health—not to mention swallowing up entire neighborhoods. However, obliterating any evidence that it had occurred seemed short-sighted. It seemed like an affront to the tens of thousands who had labored in the mines and associated operations.

Despite their turbulent history, Buttians never lost faith in the city. Since the day that gold was discovered at Silver Bow Creek through the booms, busts, mining disasters, labor disputes, political intrigue, and martial law, they’ve seen it all.

Gobs of ideas were batted around related to historic preservation and interpretation. It was clear that the city needed some sort of vision and plan for achieving its long-term goals. Thus, the creation of the Butte-Anaconda Historical Park System Master Plan in 1985. While I didn’t know much about historic preservation, I did know how to write park-management plans, and was hired to play that role in the project.

Our vision was ambitious: a series of interconnected historical units including the remaining Butte mineyards and smelter-related sites in Anaconda. Some would be restored, some mothballed but left standing, and some, through environmental remediation, turned into parks and greenways.

It was an exciting plan. But in the end, just a plan. In 1993 it inspired the drafting of a related document, “The Regional Historic Preservation Plan,” but like many community-development blueprints, both could have easily been relegated to gathering dust on a shelf. Miraculously, though (well, actually thanks to the hard work, creativity, and tenacity of a dedicated group of people who loved Butte), many of the projects proposed in those two plans have since become realities.

Dori Skrukrud is one of these hometown heroes. Dori is the Butte Community Development Coordinator and has been shepherding the effort for the past quarter-century. Her stories about related challenges and opportunities are mind-boggling. Nothing is easy or straightforward when it comes to environmental remediation. Of special interest to Dori and others was the cleanup of Silver Bow Creek and the creation of a trail system along it. Dori recounts how when she first engaged in “the largest stream-replacement project ever undertaken,” a century of underground and open-pit mining had turned it into a dead zone. Nevertheless, Dori and her colleagues were not just satisfied with reclamation. They wanted to see restoration. Talk about raising the bar. And raise it they did. “Now when I go down there,” Dori says, “I see beavers, bald eagles, deer, all kinds of wildlife.”

Nothing is easy or straightforward when it comes to environmental remediation.

She also wanted to see humans safely enjoying these once-despoiled landscapes, and set about refining plans for trails, parks, and interpretation. That’s when the really hard work began. It included negotiating easements, buying properties, and the complicated process of coordinating outdoor-recreation developments with the reclamation efforts of myriad agencies. But as benefits of these initiatives became clear, so did Dori and her colleagues resolve to bring more projects to fruition.

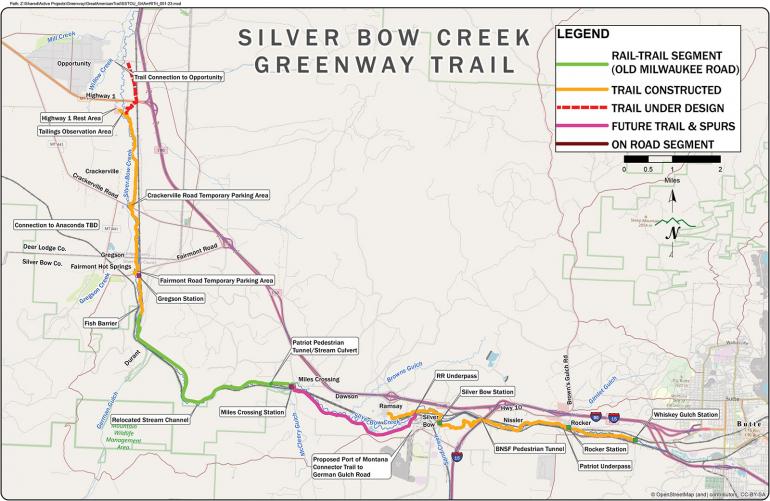

And voila! The Silver Bow Greenway Trail now includes about 13 miles of completed paved trail, with more construction underway, for a total of about 30 miles. It also connects with other existing trails, linking the top of the Butte Hill to the Greenway. Eventually it will extend all the way to the Opportunity Ponds, northwest of Anaconda. Much of it is already paved and in place, including bridges, benches, tunnels, interpretive signs and even restrooms. There are several other urban trails, completed and in the works, all open to nonmotorized use. And that use is ever increasing by the year.

A Ride into History

I like to celebrate my birthday by doing something outdoors, and memorable. So last year, when the weather forecast for my special occasion indicated a bluebird autumn day, I decided to throw my bike in the back of the truck and head to Butte. There was no question that I was going to ride the Greenway and other trails. But should I begin at the top of the Butte Hill and ride downhill? Or start along Silver Bow Creek, and ride uphill? In defiance of the number of candles on my birthday cake, I headed up.

There is an interactive map on the Butte Silver Bow Parks & Recreation website where you can explore many of the town’s outdoor-recreation options and facilities. I started at the Rocker Station trailhead just off I-90. There, the Greenway Trail follows Silver Bow Creek in two directions, back towards Butte, but also west all the way to the little community of Ramsay where the paved trail currently ends. It picks up again some six miles further west and continues all the way to Hwy. 1, which links Anaconda to the interstate. Efforts to connect this last gap in the trail system are ongoing.

I rode in the opposite direction toward Uptown. While the trail along Silver Bow Creek is paved, I opted to save that for later in the day and started up the BA&P rails-to-trails section. This spur trail is the abandoned Butte Anaconda and Pacific Rail Line that once tied together several of the mineyards and was critical infrastructure for mining and smelting operations. The first section is unpaved, but fine for walking or any type of bike. The trail passes through a tunnel underneath I-90, and soon after arrives at the World Museum of Mining next to the campus of Montana Tech. This funky but lovable museum includes eclectic mining artifacts and a recreated early-day Butte mining camp, complete with all manner of shops and businesses—from churches to brothels. There’s an actual mineyard and headframe on site.

Perhaps the most poignant stop is the end of the trail at the Granite Mountain Speculator Mine Memorial—site of one of the world’s deadliest hardrock-mining disasters, that claimed the lives of 168 men.

The trail is paved after that, and continues to switchback up the hill, passing through Butte’s historic neighborhoods with an amazing diversity of housing styles. It also skirts other headframes and mineyards. Interpretive signs recount their colorful histories. The best preserved—the Anselmo Mine—is open to visitors during the summer.

Some interpretative signs even focus on things that no longer exist, like entire neighborhoods that were sacrificed to expanding mining operations. But perhaps the most poignant stop is the end of the trail at the Granite Mountain Speculator Mine Memorial—site of one of the world’s deadliest hardrock-mining disasters, that claimed the lives of 168 men. It is well-interpreted with testimonials of survivors, recorded stories, maps, and beautiful metalwork. It also offers an expansive view of the open-pit mining operations that will blow your mind.

I retraced my route back toward Montana Tech, but then cut through historic uptown on streets, alleys, and sidewalks, all the way down to the Silver Bow Greenway Whiskey Gulch Station. There, the character of the ride switched abruptly from industrial and urban to a much more natural, almost wild setting. Signage also changed with a focus on ecological restoration. Replanted willows and other vegetation along Silver Bow Creek provide habitat for a variety of species. And, astonishingly, native trout have begun to re-emerge in the waterway.

Eventually I arrived where I started, at the Rocker station and my vehicle. If I’d had the time, I would have grabbed a cold beverage at the Bluebird Bar near the trailhead, but that’ll have to wait for my next birthday.

Butte Reincarnated

Despite their turbulent history, Buttians never lost faith in the city. Since the day that gold was discovered at Silver Bow Creek through the booms, busts, mining disasters, labor disputes, political intrigue, and martial law, they’ve seen it all. If anything, that history has cultivated a tenacity that has become an integral part of the famous Butte character.

That tenacity is visible today in the herculean clean-up efforts still underway. Check out the town, and maybe you too will marvel at humankind’s ability to turn a mountain inside out, and then try to put it back together. And, while in that process, create recreation opportunities that are singular in America. It will elicit a wild range of emotions. But if you have a love of Montana history, and an adventurous spirit, I think you’ll dig it.