Dogs' Years

Osteoarthritis in canines.

Most Bozeman dogs lead an active lifestyle, taking part in all the outdoor activities the rest of us enjoy. For both people and pets, as we age and recover from injury, we’re sometimes confronted with discomfort associated with osteoarthritis (OA). OA can be a debilitating condition, limiting mobility, function, and quality of life. It’s often assumed that, like us, our canine companions suffer from arthritis as a natural consequence of aging, and that little can be done other than treatment with medications. This is often not the case. In order to understand OA in our dogs, it’s helpful to explain how arthritis develops in dogs and how that differs from its development in humans.

OA can be divided into two basic categories: primary and secondary. Primary OA is what we are most familiar with, the gradual and chronic inflammation in a joint from years of wear and tear. While common in people, this form of OA is actually rare in dogs. The development of OA in dogs is generally secondary to some other condition or underlying cause such as a congenital, developmental, or degenerative problem, or a traumatic injury.

Treatment of secondary OA with medications such as anti-inflammatories can be beneficial in lowering inflammation and improving comfort. However, the most effective treatment is addressing the primary condition.

The place to start is a thorough orthopedic exam. This can focus the problem to a specific joint and, in the hands of a seasoned practitioner, provide a definitive diagnosis. X-rays and more advanced imaging such as ultrasound, CT scan, MRI, and arthroscopy can be helpful in more difficult cases.

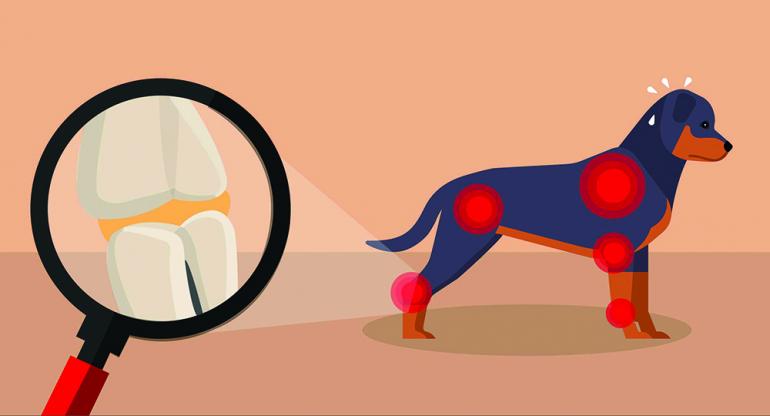

OA can affect any joint, but a few are more heavily represented in dogs. OA in the elbow and knee, and hip in the rear, is common. When OA develops in the hips and elbows, it’s usually from a congenital cause such as hip or elbow dysplasia. Even though the dysplasia has been present from very early in life, lameness may not present until a dog is older. In the knee, the most common cause of OA is from instability associated with tearing or degeneration of the cranial cruciate ligament (CCL). This is similar to an ACL injury in a person.

The instability associated with a CCL tear is generally more uncomfortable than the secondary OA. Surgical procedures can stabilize the knee and return dogs to normal function. Elbow and hip dysplasia can manifest in a multitude of ways. Treatment for these conditions varies with your pet’s stage of development, age, and severity of condition.

Historically, once OA progressed to degenerative joint disease resulting from cartilage erosion and bone-on-bone contact, little could be done other than symptomatic treatment with anti-inflammatory medication. This was especially true in the elbow, but fortunately is no longer the case. Total hip replacements (THR) for the treatment of end-stage OA in the hip as well as Canine Unicompartmental Elbow (CUE) resurfacing procedures now exist. In the past, these joint and partial-joint replacement techniques were either not readily available or were considered extravagant for many canine patients. Now these procedures are routine. THRs, CUEs, and many other procedures have been developed to return an active dog back to a high level of function and most importantly, comfort.

Pets are important members of our family. They are our recreational companions, co-workers, and friends. Nowhere is that more evident than here in Bozeman. Our dogs do everything with us, so if OA and what has been assumed to be “old age” is slowing your dog down, there may be options. A trip to your veterinarian is a good place to start.

Dr. Jason Wheeler is a veterinarian with the Gallatin Veterinary Hospital in Bozeman.