Fathers, Sons & Ski Days

It’s late November. It’s dumping—the first good snow of the season. I’m standing on my porch watching the white flakes fall seamlessly out of the darkness above, letting them gather in my hair, on my jacket, on my eyelashes. My girl sits inside, watching TV with our boy—a week overdue and the size of a bowling ball—still in her belly. Only one thing is supposed to be on my mind: at any moment, I could be a father. But a lingering thought of a life almost entirely gone by still flutters like the snowflakes on the wind: powder day tomorrow.

“We’ll have the kiddo up on the ridge by the time he’s two weeks old.” That’s what my brother had told us.

My girl scowled at him. “You absolutely won’t.”

“Sure, we’ll get him one of those backpacks. He’ll love it.”

“He won’t even be able to hold his head up at two weeks.”

I surveyed my brother. He hadn’t thought of this. “Maybe we’ll wait a month then,” he said.

My brother stands up on the ridge, waist deep, with only a shovel and a snack in his backpack. I’m standing in Bozeman Deaconess, supporting the neck of my newborn son who sleeps quietly in my arms, looking out the big window at the fresh blanket of snow on the Bridgers. A part of me feels at ease, contented, like a conquering hero, a man. Another part of me feels like a caged bird, like a polar bear tentatively walking over thin ice 20 miles from shore. And I feel ashamed.

There is a fine line between being a good father and a good skier. We hadn’t expected to get pregnant. I came home from work and took one step inside the door. Instantly upon seeing my girl tying up the garbage to take it out, I asked what was wrong. Just as instantly, she responded that she was pregnant. I remember staring into the darkness at the silhouette of the Bridger range cutting north into the night, trying to take hold of the reality. I remember trying to think of how to react, my mind being too flustered to simply do so on its own.

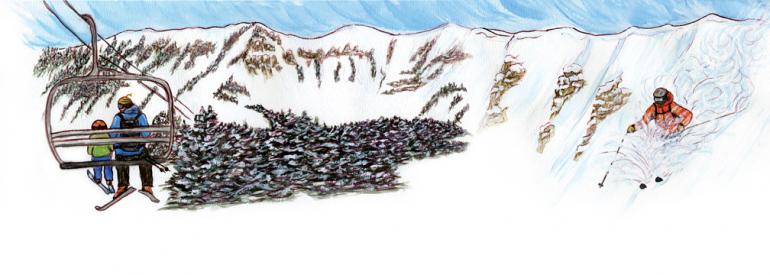

I remember smoking a Pall Mall, staring at the burning ember at the end knowing it was going to have to be one of my last. And then a feeling of calm washed over me. I remember peaceful warmth. I realized where I was, how I had enviously declared to every native Bozemanite I had met in my four years since moving here from the East how much I wish I could have grown up here. And now I was going to able to raise a child here—the next best thing to growing up here myself. I thought of sharing powder turns with my boy, showing him around the ridge, where the good hits are in the A’s and taking him on the long hike out to Z-chute. I thought of watching him progress, watching him grow into his own style—powder hound or park junky. I thought of the slow chair rides on warm spring days, lecturing him on the good ol’ days of trackless powder fields and ski clothes that didn’t resemble clown outfits. I thought of the whole gambit of conversations to enjoy and turns made before that Pall Mall burned to the filter.

But there are the in-between times—when he can’t hold his head up or wipe his own ass. Times when powder days have to be passed by so he can lie in my arms all day because mom needs to sleep—for the love of God let mom sleep. There’re the times when twenty-dollar day at Big Sky has to be missed because the little bugger’s got his sixth checkup in as many weeks and the appointment is right smack dab in the middle of your only day off. It’s in these moments that a man needs to ask himself whether he can be both a good father and a good skier.

How many missed powder days before a man loses the feel of bottomless snow beneath his feet? Or how many missed birthdays to ski before the boy begins to feel neglected? How many seasons of five days out before a man loses his edge? Or how many missed good-night stories before the kiddo stops asking for good-night stories? The little bugger needs diapers. And I don’t mean he has a few left and we can get by for a week. I mean the diapers he’s wearing now are a size too big and every time he takes a piss we have to steam-wash the couch. But, as it always goes, my bindings are beginning to crack; they’re bound to break any turn now. There’s only enough money in the bank to remedy one situation. And of course, it’s 7am, dark out, zero degrees on the nose, and I’m headed to Smith’s to find the right-sized diapers. But as I drive the lonely streets, I can’t help but wonder, can’t help but dread, that when the day comes, the day of daydreams, will my boy be ditching me to go ski some line on the ridge I have somewhere between now and then lost the nerve, the ability, or the edge to ski? Will I be too out of shape and beer-bellied to hike? Will he get sick of waiting up top while all the other hikers trudge past his lumbering dad and take his powder turns?

Well, you needed diapers.

Is that what I’m going to tell him?

I had to sit on the couch holding you all day so mom could get some sleep.

Is he going to give a damn about that? Or will he say, as I’m sure I would have told my pop (had he stuck around long enough to hear it): you should have fixed your bindings and kept on steaming the couch Dad. Or maybe, if he’s at all like his uncle: you should have just bought one of those backpacks and made me sleep in that all day while you got your turns. Will I be stuck riding Alpine Lift alone all day, telling my boy to meet me in the lodge when he needs a ride home? Good Lord, the idea alone is frightening.

I love my son ferociously. I want him to have everything. I want to protect him from even the smallest of life’s woes. For example, when his old diapers were giving him diaper rash, I didn’t want to just change brands—I wanted to go to the Pampers factory and burn it to the ground for harming my boy. But what is this love creating? By loving, nurturing, and hopefully creating your perception of a good man, do you have to accept the reality that when the job is done, you’ll be too washed up to keep up with him? God, that’s a miserably terrifying thought.

There is a fine line between being a good father and a good skier. I don’t yet know which I am better at, but as I drive home from Smith’s through the gathering snow with a car-full of diapers and a ski with a broken binding (which I’m going to have to get into the shop one of these days), and, leaning against the wall in the basement, I have a pretty good idea. And I’m fine with that.