Passing the Pulaski

Fighting wildfire from one generation to the next.

My kids grew up in a house where at any time they might awake to a pile of stinky fire gear in the garage and mom sound asleep after returning from a 21-day assignment. Over the years, the flames have intricately framed our lives together, bringing us closer in ways I never could have foreseen.

I started with the U.S. Forest Service in Wyoming in 1984. Fire remained a large part of the job throughout my 31-year career at the Forest Service, and through my kids’ childhoods.

Despite hearing stories of narrow misses from falling snags, or about one night spent on a rocky ridge as fire burned all around my crew, my son Zach joined a Forest Service engine while in college. To my delight, we ended up on a fire together. After graduating, he went a different direction, and now it is my other son Chris who has joined the Forest Service in Colorado as a fisheries biologist and resource advisor on the fireline. Though the tactics and tools between our times have changed, the heart and soul of firefighting have remained much the same.

The Early Days

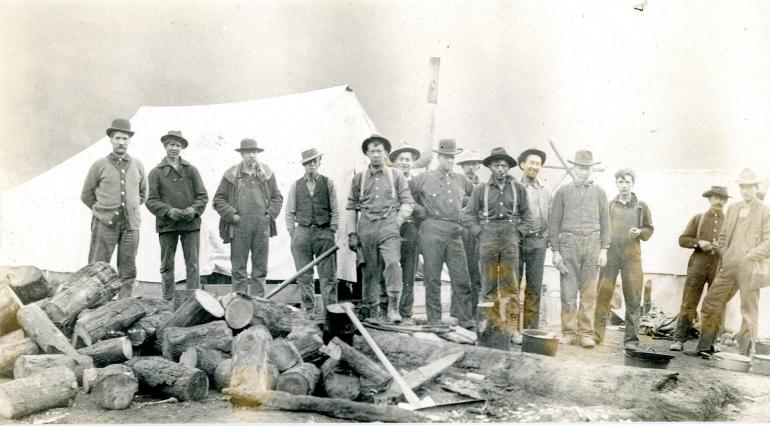

Although many think of today’s early fire seasons as unprecedented, the history of firefighting has roots in similarly brutal years. During the Big Burn of 1910, when wildfires burned roughly three million acres of Idaho, Montana, and Washington forest, the need for firefighters was severe. The rangers of the five-year-old, lightly-staffed Forest Service set up recruiting stations for men (just men, at the time).

Nearly 10,000 were recruited; anyone with a pulse was considered fit enough. As Elers Koch wrote in Forty Years a Forester in 1998, “The modern Forest Service has things pretty well organized, so that it is usually possible to get competent fire crews from logging camps, mines, and the like. But in the earlier days, we had to gather together such men as we could get from the streets, the saloons, and off the freight train. As a result, there was almost as much misery from handling the men as with fighting the forest fire.”

Without all the computerization and real-time communication that supports fire suppression these days, fire assignments in the ’80s were not nearly as efficient.

It took a strong will to command a fire crew in those days. In perhaps the most famous example, Forest Ranger Ed Pulaski saved all but five of his 45-man crew by leading them into an Idaho mine tunnel and threatening to shoot any man who left. And yet, 86 less fortunate souls still perished in the Big Burn, rattling the new agency and providing it with a sense of purpose: extinguish all wildfires.

My Time on the Line

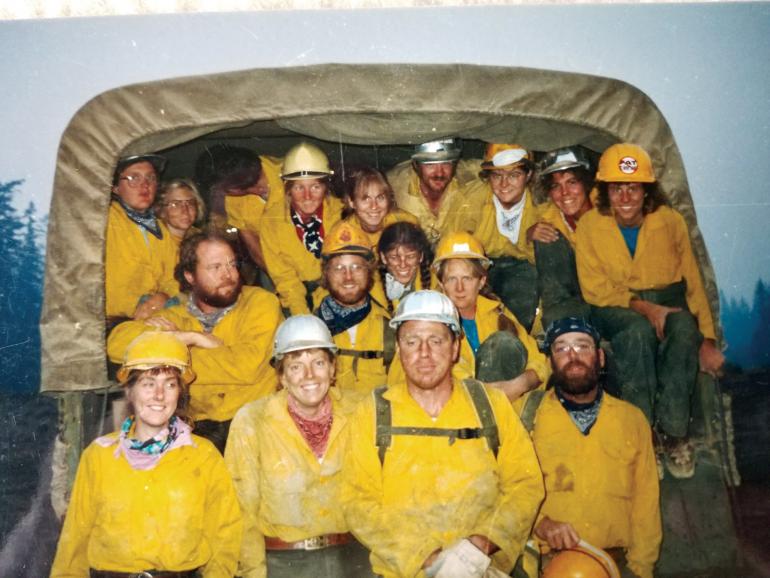

The summer of 1985 was my first season. We were a put-together crew of foresters, hydrologists, engineers, and archeologists—there were no dedicated recreation staff yet. It was an improvement from those recruiting stations a few decades prior. By then, we also had to earn “red cards,” required to go out on fire assignments, by passing a five-minute step test in which one stepped up and down a 16-inch box (13 inches for women) for five minutes at a rate of 22.5 steps per minute (there was a metronome). Later, after 1998, a firefighter would have to pass a more rigorous test—carry a 45-pound pack for three miles in 45 minutes.

We worked without “line gear”—backpacks later developed specifically for working on the fireline. Instead, we rigged up systems to carry everything but our Pulaskis on our belts—and worked hard to keep our pants up! We had canvas holsters for plastic canteens with loops that snapped over our belts, and lunches in plastic bags long enough to loop around the belts. Our headlamps were connected by cords to battery packs we carried on our belts. We had newly developed fire shelters, in narrow, bright-orange pouches with the belts built in. Our fire-resistant Nomex shirts had recently changed from bright orange to yellow—still visible to pilots, but not the same hue as the flames, as too many firefighters had been doused with slurry drops from helicopter pilots who thought the shirts were active fires.

Without all the computerization and real-time communication that supports fire suppression these days, fire assignments in the ’80s were not nearly as efficient. “Hurry up and wait” was a common refrain, and during the down times, while waiting to be picked up at checkpoints (by deuce-and-a-half military-style crew carriers, for example), the sound of harmonicas was common, or maybe the shouts of a hackysack game. The ability to sleep anywhere was a useful skill (and still is). One of my crewmates could even sleep in a rolling cargo truck.

Cameras were still film, and too valuable to carry on the fireline. I’m glad there are no Instagram posts of my soot-blackened face at the end of a day—just memories of all the laughter that the sight provoked. Every now and then, though, we got to wash up in a makeshift shower or bath of some sort. One night, after three days straight of digging line, we descended a very steep slope in the dark (night shifts were routine business then), using fire hoses devised into a belay system. At the bottom, our fire boss got us permission from a local rancher to wash up in a nearby stock tank, powered by an old Chicago Aermotor windmill. Again, no photos, just memories.

Fires Grow

Even by the time I started fighting fire, the Forest Service’s efforts were effective enough that I thought a 10,000-acre fire was huge. The contrast with my son’s present-day experiences is striking. Chris saw 40,000-acre days on the Cameron Peak Fire in Colorado in 2020.

The scale of the Cameron Peak Fires approached that of the Yellowstone Fires of 1988, when 150,000 acres burned on one fateful day in late August, subsequently known as “Black Saturday.” The Yellowstone fires were the first instance of drifting smoke affecting folks beyond small mountain towns. They were the first fires to catch my generation’s attention. In response, an industry started to build around firefighting.

My son's fire experience has been defined by watching simultaneous plumes from the 209,000-acre Cameron Peak Fire, 194,000-acre East Troublesome Fire, and 177,000-acre Mullen Fire from a single lookout tower in the fall of 2020.

One of the most popular improvements to arrive in fire camp was the communications tent, where a bank of telephones was brought in for firefighters to call home. However, it could be supremely disappointing if no one was at home to answer your attempted call after standing in line for half an hour. That prompted me to use one of my early fire checks to go home and buy an answering machine.

We also saw the advent of shower units and food trucks. While my lunches might have been provided by local restaurants when available, there was always the chance that we’d get nearly inedible military MRE’s or even older military C-rations. My son’s lunches now include fresh fruit and vegetables—oh my

Significant changes have been driven by the benefits of—and dependence on—digital devices. My fire crews were handed paper shift plans at 5am briefings. These included maps with crew assignments; locations of heli-pads, drop points, mobile water pumps, and medical clinics; and a list of radio frequencies for each division of the fire.

Nowadays, crews travel with devices for downloading and plotting perimeter maps, forecasting fire behavior, using drones, or crew timekeeping. Where our Incident Command Posts (ICP) used to be close to the fire, with “spike” and coyote camps on the fireline, they’ve now migrated so far down valley to be close to necessary infrastructure that there’s a newly added layer of camp: the Forward Operating Base (FOB). The prolific use of three-letter acronyms, however, has clearly remained, despite new technologies.

Critical life skills learned in the mountains and on the fireline have been extended to other family ventures, and to being part of any team or community.

Then there’s the changing climate. While I could look forward to “termination dust” (snow) by mid-September back in the ’80s, the 2020 Cameron Peak Fire that my son worked on wasn’t declared contained until December 2. Since fire “season” is now year-long, there is much less reliance on “militia” crews, made up of employees for whom firefighting is a collateral duty, as it was for me. The Forest Service today also has a lot more balls to juggle. While the focus of current suppression efforts is on the front-country and threatened structures, my son also has to respond to ignitions in the backcountry. With most forest ecosystems so far out of alignment from historic fire regimes, Chris is aware of just how quickly remote fire starts can threaten front-country communities.

Chris’s fire experience has been defined by watching simultaneous plumes from the 209,000-acre Cameron Peak Fire, 194,000-acre East Troublesome Fire, and 177,000-acre Mullen Fire from a single lookout tower in the fall of 2020. It’s one thing to watch ginormous California fires on the news, but it’s quite another to have your favorite trout stream turned into a temporary thermal feature. In his words, “That event radicalized me,” clarifying for him both a sense of purpose and urgency. He wonders if the agency isn’t feeling an existential crisis akin to the period following the 1910 fires.

Continuum of Firefighters

In the end, there are some basics that haven’t changed in many decades, like using a Pulaski tool to dig line, or the reliance on protocols to keep us safe. Everyone these days is coming to terms with climate change, and while some have seemingly been more insulated from the impacts, firefighters have confronted them directly. While we continue to work out how to live with catastrophic fire and its impacts on the ecosystems which we are part of, for those that fight fire, whether for a few seasons or a lifetime, there’s a sense of being part of a continuum of folks dedicated to each other and their communities.

My own family is part of that generational continuum. We share an understanding of the challenges of losing a cherished landscape (or more), and realize just how fragile the wishful paradigm of a static environment—or even a Forest Service—really is. But in addition, we have all the questions that come with family. What did my absences on fire assignments mean for my kids, when dad and family stepped up? Did my young kids benefit from the sense of confidence that firefighting bestowed on their mother?

Critical life skills learned in the mountains and on the fireline have been extended to other family ventures, and to being part of any team or community: situational awareness, communication, looking out for each other, and providing safe zones. My sons observed and learned that a sense of camaraderie earned on fire crews carries over to teamwork of another kind: the day-to-day business of forest management that is anything but routine. This style of respectful engagement is of immense value to my kids. I see them seeking and doing the work to maintain it throughout all aspects of their own lives, and we will always have each others’ backs, on or off the line.

Changing Demographics on the Fireline

Although I served as a squad boss for an all-female crew and worked on another crew that was mostly women in the ’80s, I saw this demographic change by the 2010s—with fewer women on fire crews. A 2023 BLM report confirmed that only 12 percent of regularly-employed wildland firefighters in the federal land-management agencies are women. On the other hand, I now see female Operations Section Chiefs, Incident Commanders, and Regional Directors of Fire & Aviation; so there are women who have stayed and worked their way into the top fire jobs.

A tribal presence was also a part of my fire experience. The first organized Indian crew, an Apache crew called the Red Hats, formed in 1948; and by 1954 had so distinguished themselves as fire warriors that they earned the Department of Interior’s top honor for meritorious service. Tribal leaders considered their work a positive reflection on the tribes; and Hopi, Navajo, and Pueblo Indian crews soon followed, including a crew called the Zuni Thunderbirds. Fire assignments were, and still are, a way for tribal members—both men and women—to earn good money when reservation jobs are scarce. I particularly loved hearing ceremonial drums in a separate part of camp after a long shift on the fireline, pairing up with these folks for pranks on crewmates, receiving the gift of a carving, or noting leather fire gloves personalized with art inked during down time.

Traute Parrie stays engaged in the backcountry through skiing, bikepacking, and restoration work on fire-lookout-towers—as often as possible with her kids, grandkids, and husband Don.