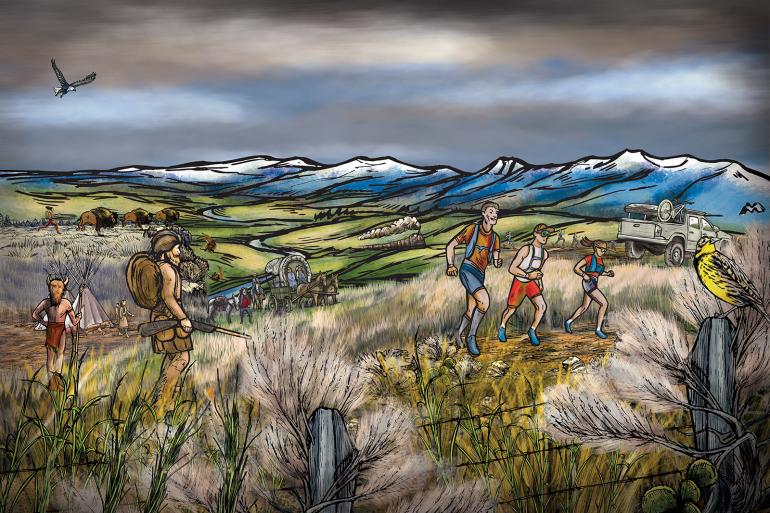

Montana Migrations

Traversing Big Sky Country through the millenia.

Humans have been drawn to the Bozeman area for thousands of years. Natives, pioneers, mountain men, stagecoaches, railways, and roads all followed travel routes that have been in existence for a long time. Where did these passageways for human migrations come from, and why? Let’s peek back through history.

Human Migration in North America

As far back as 15,000 years ago, people began migrating on foot across Beringia, a landmass spanning what is now the Bering Strait. Following animal migrations, they left northern Asia, crossing Alaska and Canada to turn south along the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains into what is now the contiguous United States, forming what we know as the Old North Trail. They eventually expanded throughout the Americas, all the way to the southern tip of Patagonia. These early inhabitants are now known as the Clovis people, who followed mammoths and left traces of their stone spear tips along the way. The remains of a young boy found in Wilsall prove that humans have been in southwest Montana for at least 12,600 years.

Later, the Sioux, Blackfeet, Crow, Hidatsa, Shoshone, Lakota, Dakota, Nez Perce, Bannock, Arapaho, Salish, Cheyenne, Gros Ventre, Cree, and Assiniboine would all use an area along the Old North Trail near Three Forks as seasonal hunting grounds. The Madison Pushkin (buffalo jump) was used for a period of 2,000 years, by the Shoshone and others, to harvest “Bo-shoen,” the lifeblood of the plains Indians.

Individuals with an adventurous spirit, physical grit, and determination to see a journey to its end have always punctuated the area now known as Montana. These standouts through time continue to inspire outdoor adventurers hoping to capture some of the rugged, wild experience of those who charted the way. Although things have changed since the inaugural inspirational events, we can still have wild experiences in our modern physical endeavors.

Madison Buffalo Jump: 1,750-2,000 Years Ago

In the age before the horse, hunters pursued the great bison herds on foot. Although we don’t know the names of the prehistoric hunters, archeological digs reveal the extent of bison harvesting in previous times.

Before the mass extermination of North American bison by Caucasian buffalo hunters in the late 1800s, who sent the pelts East on the railway, bison filled the entire landscape. It’s estimated that as many as 30 million roamed North America at the time of the Lewis & Clark expedition.

Tribes used every part of the bison for food, shelter, and supplies. The animals were sacred. They performed a ceremony to thank Bo-shoen for its sacrifice. This was the way of life for many generations.

Chosen young braves, with the right fitness and skills, fulfilled the great honor and responsibility of a buffalo runner. The whole community set the stage for the runners to bring home the bacon. Dressed as wolves or calf bison to not alarm the herd, hunters gathered around the grazing area, gradually coaxing the herd into cairn-marked drive lines. At a crucial position and moment, the costumed hunters, who waved animal skins and made loud noises, spooked the herd to trigger a stampede.

Now it was the runners’ turn to complete the kill by leading the stampeding herd to the edge of the cliff at a full sprint. Guiding the rushing herd, the runners would duck away at the last moment in a cleft in the cliff while the herd careened over the top of the pishkun, which means “deep blood kettle.”

It was a dangerous but necessary task. One can only imagine how a young brave would prepare for such a task—sprinting full-speed, navigating obstacles, running alongside massive animals, and jumping the precipice at the exact predefined crevice, as the bison charged overhead. This must have required incredible focus and timing.

Madison Buffalo Jump: Now

Though the purposes of these experiences were crucial for the survival of ancient Montanans and weren’t seen as recreation, there is something innately human about exploring what is unknown and pushing past the edge of the familiar, past physical limits of strength and endurance.

Today, you can visit the Madison Buffalo Jump on foot, bike, or horseback. Hike the series of trails up, over, and around the historical site. It’s also great for shoulder-season mountain biking. Although there is no longer the danger of being stampeded by a herd of bison, look out for rattlesnakes and prickly pear cactus. Be mindful of the limestone cliff exposures and the hot dry conditions in the summer. Pack more water than you think you’ll need.

Lewis & Clark: 1806

One of President Thomas Jefferson’s primary goals for the Corps of Discovery was to find a water route between the Missouri and Columbia rivers with a minimal Rocky Mountain portage. Lewis and Clark had not achieved this on their westward journey to the Pacific.

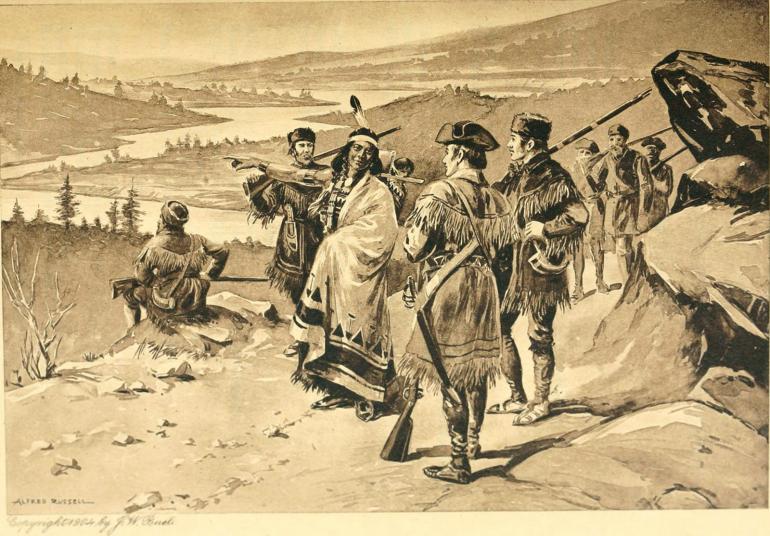

On the return trip, the expedition split at Three Forks. Lewis went north on the Missouri to explore the extent of the Marias River, while Clark, guided by Sacagawea (carrying baby Pomp) went with a group of 10 men and 49 horses into the Gallatin Valley. Clark mapped the journey, reuniting with Lewis a month later at the junction of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers in western North Dakota.

Navigating east along the Gallatin River and following the snow-capped Bridger Mountains, they spent the first night camped along this “beautiful navigable stream” east of Logan—ironically, the site of our current landfill. By comparison to many challenging stretches of the expedition, this portion was fairly uneventful, with historians proclaiming it as “Clark’s interlude of pure enjoyment.”

Animals were plentiful in the valley, including beavers, which made a significant impact on the flow of the river. Avoiding swampy ground and bogs not suitable for horse travel, the Corps found old bison paths, well-known by Sacagawea and other indigenous people, through what is now Manhattan and Belgrade. They were able to travel this stretch with little complaint.

Moving along the East Gallatin River, they moved south to avoid more beaver construction near the present-day fairgrounds. They crossed over Sourdough Creek along what is now Kagy Blvd., making their second camp in a meadow along Kelly Canyon Rd. They continued up Kelly Creek to Jackson Creek, past Green Mountain northeast of Chestnut, then to Billman Creek before connecting to the Yellowstone River. This section is slightly north of current-day Bozeman Pass.

Sacagawea had advised the group to cross this gap south of the Bridgers to exit the valley. They found trees large enough to carve two dugout canoes near present-day Livingston for their journey down the Yellowstone River.

Lewis & Clark: Today

Most of the footpaths along the Gallatin Valley were converted to stagecoach trails, then highways. These days we can’t travel most of the historic routes on horseback, as large sections are now where I-90 runs. These modern-day migration routes are basically the same paths ancient bison herds created as they migrated through the area.

Colter’s Run: 1808

The legend of John Colter’s escape from a large group of young Blackfeet braves has inspired books, films, and a trail race.

Colter’s fitness and survival skills were first developed in his years working as a guide in the Kentucky frontier, where his ranger skills impressed Lewis and Clark enough for him to be hired on to the Corps of Discovery. He served as a navigator, hunter, and negotiator between the various tribes along the route to the Pacific and back to St. Louis.

Itching to get back to the land rich with beaver, Colter was honorably discharged from the expedition a few months before its culmination.

Individuals with an adventurous spirit, physical grit, and determination to see a journey to its end have always punctuated the area now known as Montana.

He joined a group of trappers heading to Three Forks in pursuit of lucrative beaver pelts. This expedition disbanded, but not before Colter first set foot in uncharted valleys. He was intrigued and continued exploring what are now Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks, making a 500-mile loop in the dead of winter through Idaho and back by Yellowstone Lake to present-day Cody, Wyoming. Colter witnessed curiosities such as boiling mud pots, geysers, and steaming waters. Returning to Fort Raymond after his journey, he told tales of the exotic lands, only to be met with ridicule. The area was mockingly named “Colter’s Hell.”

Undeterred by previous hostile encounters with the Blackfeet, Colter led a group of 800 Crow and Shoshone back to Three Forks to negotiate trade. On the journey back to Fort Raymond, 1,500 hundred Blackfeet warriors attacked the party. Colter’s groups eventually pushed back the Blackfeet, with Colter sustaining a leg injury in the process. He recovered at Fort Raymond.

As soon as he healed from the battle injury, Colter returned again to Three Forks via the Jefferson River in canoes, with partner John Potts. Before reaching Three Forks, they encountered a group of several hundred Blackfeet along the riverbanks. They motioned Colter and Potts to come ashore. Colter complied and was promptly disarmed and stripped nude. Potts refused, and shot and killed an Indian on the shore. He was immediately riddled with bullets and arrows, then dragged to shore and chopped to pieces. This practice ensured that he wouldn’t be able to seek retribution in the afterlife.

A council was held to decide what to do with Colter. Convincing them he was a slow runner, he was told to flee on foot. Many young braves began to chase Colter across the landscape where he ran for his life. After a few miles at full speed—barefoot, nude, exhausted, and bleeding from the nose—Colter had separated from most of his assailants, with one brave trailing a few dozen yards behind. Worried about being speared in the back, Colter abruptly stopped and turned to face the brave with his arms outstretched. Startled by Colter’s appearance, the brave tripped while attempting to launch his spear, thrusting the tip into the ground and breaking off the head. Colter overcame the brave and used the spearhead against him. Taking the fallen brave’s blanket, Colter resumed flight. After running about five miles from the starting point, he found a beaver lodge on the Madison and hid inside. At nightfall, once the coast was clear, Colter walked for 11 days to a trader’s post 250 miles away at the Bighorn River, surviving along the way on roots and berries.

It is possible that the plan was to terrify Colter and let him survive, so that his harrowing tale would scare off other trappers. The beaver was a sacred animal to the Blackfeet.

Read more about John Colter’s life and legendary explorations in John Colter: His Years in the Rockies by Burton Harris.

Colter’s Run: Now

Colter’s athletic prowess, running speed, endurance, and cunning saved his life that day and inspired the John Colter Run, hosted by the Big Sky Wind Drinkers running group. The course is set at the Missouri Headwaters location of Colter’s naked run, following 7.5 miles of rugged trails. The rough terrain, which includes two river crossings, looks much as it did over 100 years ago when Colter inspired the route.

Enjoy the thrill of the chase with 300 other trail runners as you imagine Colter’s extreme motivation on your way to the finish line.

The Bozeman Trail: 1864-68

By the mid-1800s, the Oregon Trail was bustling with pioneers, many of whom had decided to take a journey north into Montana upon the discovery of gold in Bannock, Virginia City, and Alder Gulch. After leaving Bannock and returning east just as Alder Gulch took off, John Bozeman vowed to return in haste, taking a shortcut back to the gold lands from St. Louis. Along the way, he veered off the Oregon Trail, leading several covered wagons northward along the east side of the Bighorn Mountains in Wyoming. Ignoring the request of the Sioux, who had won hunting rights to the Powder River Basin in prior tribal wars, Bozeman continued north while many in the party heeded the warning and turned back south.

Meanwhile, famous mountain man Jim Bridger guided covered wagons along the west side of the Bighorns. Bozeman, after getting lost and heading toward Billings, corrected course and rejoined Bridger’s route westward along the current I-90 route through Livingston. Bridger followed the Shields Valley northwest, crossing into Bridger Canyon to reach current-day Bozeman, whereas Bozeman crossed more directly over Bozeman Pass into the Gallatin Valley.

Bozeman’s route became known as the Bozeman Trail, where subsequent forts were established as military outposts to protect wagon trains from Indian raids. After a few years of conflict, the Oglala leader Red Cloud won a treaty securing the greater Powder River Basin and lands along the Yellowstone as his hunting grounds, if there was a viable livelihood to be made from traditional hunting of elk and bison.

In 1868, Red Cloud signed a treaty with the U.S. government that guaranteed closing the forts along the Bozeman Trail, including Fort Ellis outside of Bozeman. Indians promptly burned the forts, ending the Bozeman Trail’s tenure and temporarily stalling the transportation route. By the late 1880s, bison had been nearly hunted to extinction for their skins and tongues, as well as their bones which were used as fertilizer back east. A winter expedition across the newly-formed Yellowstone National Park led an animal count, including the remaining bison population. Poachers were caught and tried, and laws were established to protect the game in the Park. But the damage had been done and the nomadic way of life for the plains Indians had come to an end, resulting in the establishment of the Crow and Rocky Boy’s reservations.

The Northern Pacific Railroad reached Bozeman by the 1880s, digging through Bozeman pass and driving the last spike in 1883 near Gold Creek, Montana. Read more at outsidebozeman.com/trains-and-the-treasure-state.

The Bozeman Trail: Now

The dominant animal and human migration routes throughout western America’s history have been north-south, along the eastern side of the continental divide and Rocky Mountains. Lewis and Clark were tasked with finding an east-west connection to promote trade across the United States. These routes charted the way for our modern-day transportation routes on roads and railways.

US Hwy. 10 was built in 1926 and replaced by I-90 in 1986. This interstate highway, connecting Seattle to Boston today, serves as the major transportation route through the Gallatin Valley, running past the airport in Belgrade, which is the busiest in the state.

Montana’s history is filled with boom-and-bust cycles, bringing people and development into the state. While the gold towns are now ghost towns, the flowing creeks persist. Spring snowmelt gives rise to summer flowers and the never-ending parade of wildlife passing through.

Navigating east along the Gallatin River and following the snow-capped Bridger Mountains, they spent the first night camped along this “beautiful navigable stream” east of Logan—ironically, the site of our current landfill.

Now it seems the latest gold-rush is the land itself. Renowned recreation abounds for outdoor enthusiasts and sportsmen alike. With tourism now rivaling the agriculture industry, it is obvious that we are drawn back to these wild places connected by the big skies of the American West. Dreams of a better life drew migrations from millennia ago and continue to do so today.

Though there is no modern comparison to the intensity of a buffalo jump, we are drawn to action sports in nature that give the rush of speed in a natural environment, thriving on the collective engagement and support of the communities around these modern-day “extreme” events, such as Colter’s Run, the Ridge Run, and the Rut, to name a few of the largest and best-known. Dozens of other events, including bike-racing, climbing, and skiing, reflect the same ongoing affinity for challenge, competition, and community.

It hasn’t been without struggle and conflict, but these wild places continue to draw migrations for a better way of life in nature’s bounty under big skies.

To see O/B's timeline of southwest Montana history click here.

Born in Bozeman, Bryan Schaeffer owns the creative studio SINTR. When he’s not outside, you can find him writing, illustrating, and animating his book series The Last Best Trails. He would like to thank Rachel Phillips from the Gallatin History Museum for gathering countless magazine articles, newspaper clippings, and stacks of books to help focus his research for this article, as well as Dr. Shane Doyle (an Apsáalooke educational and cultural consultant who hails from Crow Agency) for hours of conversation about human migration in southwest Montana and the historical practices of indigenous people in the area.