I Know What You Did Last Ski Run

Andy Rooney nailed a verbal bulls-eye when he said, “Computers make it easier to do a lot of things, but most of the things they make it easier to do don’t need to be done.”

This is especially evident as I approach hour five of sitting at my desk, before two notebook computer screens, gathering ski reports from ski areas I have no plans on skiing at this year.

Getting a mountain report used to require dialing a phone number and then listening to a contrived, cheery voice detail how much new snow fell, how many runs were open and that, without fail, described conditions as “packed powder.”

But according to Greer Schott, the Public Relations and Special Events Coordinator for Big Sky, webcams are fast becoming the prevailing choice for ski condition updates. Locals, Schott told me, champion the live shots for checking snow cover and visibility, while future visitors favor them for heightening anticipation. On average, she added, Big Sky’s webcam receive almost 40,000 hits a month.

It’s an astounding number to grasp until you visit Big Sky’s interactive 360 cam, as I did four hours ago, and realized the attraction.

This camera, located at the base of Big Sky, possesses the addictive qualities of a video game. Through the use of your computer’s mouse you can zoom, tilt, pan and even adjust the camera’s brightness. And because there’s usually a waiting time of three to four minutes, you’re allotted only 45 nerve-anxious seconds to capture and frame your desired shots, heightening its draw-factor.

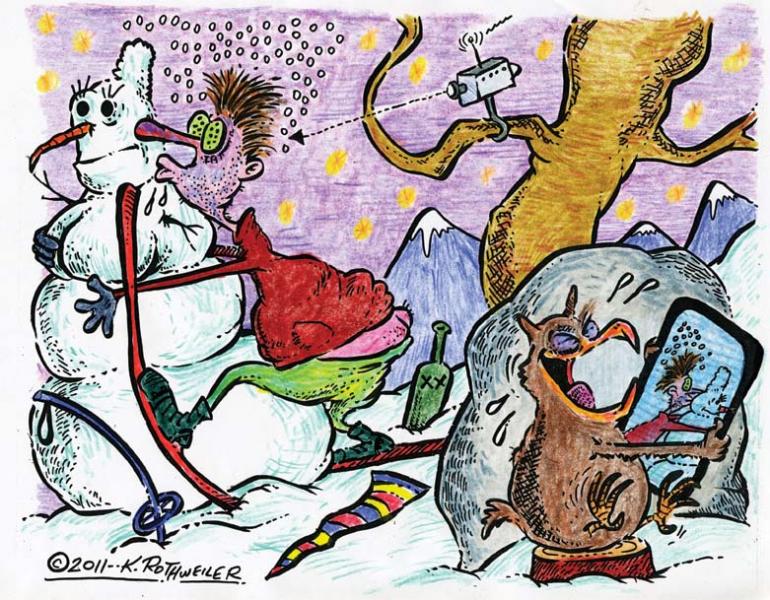

When my turn came to play director my selfishness shocked me. Instead of respecting the camera’s true touristic intentions I adopted the mindset of an art house film director, focusing on a stack of cinder blocks wrapped in cloudy plastic from an adjacent construction site. I then tried to instigate some action-drama by zooming in on the curtained windows of a second-floor hotel room—The Summit, I think—hoping there’d be some guy inside watching, prompting him to storm out the door jacked with rage and menace and heave a complimentary soap bar towards the camera. And then I ended my directorial debut playing investigative reporter by framing a close-up shot of two women and a guy, all victims of horrible hat hair, gobbling sandwiches and drinking dark draft beers at an outdoor patio table directly below me.

Most webcams aren’t as entertaining as Big Sky’s. Takamagahara, in Japan, for instance, features a time-delayed webcam photo, snapped through a crooked window blind’s beige colored slats, overlooking a three-bay garage and a closed ski lift. It’s the ski-area equivalent of Nick Nolte’s mug shot.

Whiteface’s Jump Cam furnishes an impressive view of the ski jump used in the 1980 Lake Placid Winter Olympics. But staring at it is like staring at Mount St. Helens—you keep expecting for something to happen but nothing ever does. Consequently, after four minutes you’re left feeling bored and cheated.

And Vail’s seven webcams all shutdown at 3:55 in the afternoon, leaving you with the same shock and disbelief as discovering a closed Taco Bell drive-thru at midnight.

What Vail officials don’t realize (or maybe they do and are simply trying to cloak trail grooming secrets) is that webcams, especially the interactive ones, are just as entertaining at night.

Killington’s K-1 Cam allows you to zoom in on the illuminated interior of an empty restaurant, fostering the tense illusion of being a night watchman, with thick ankles and a heavy Boston accent, looking for spring break hooligans crazed on Genesee Cream Ale.

And Squaw Valley’s Uber Cam, at 8,200 feet, casts a murky night picture, creating the high-drama sense of operating an extreme-depth oceanic camera, minus, of course, one of those Cousteau boys barking directions.

But as I’m learning now, in my fifth hour of mountain webcam surfing, the original appeal factor of having instant access to unlimited ski information eventually becomes secondary to the euphoric sense of being omnipresent. Not in a deity-type way, like I should be writing parables about mustard seeds. But more like an astronaut, with powerful binoculars, looking down from the space shuttle, while taking a needed break from studying the anti-gravitational effects on argyle socks.

I’m especially reminded of this now as I observe three skiers adjusting their ski pole wrist bands in one of Bear Mountain’s four webcams. As I eagle-eye them, a blizzard of hard questions storm through my brain: Who are these people? Where are they from? And, ultimately, do they harbor any clue that they’re being spied upon by an unshaven rube dressed in green flannel pajama pants and a Santa Cruz Surf Museum t-shirt from two time zones away in a snowbound cabin in the Rocky Mountains?

Probably not. Because if they did they’d wave, make a face, or exhibit some other manner of half-witted acknowledgment. For as a species we are incapable of passing a camera without innately switching into king-fool mode. Football games and the Today Show are high evidence of this. I imagine it’s only a matter of time before every skier and boarder becomes self-consciously aware of mountain webcams and feel compelled to react. I know I will.

Next time I ski I’m going to stand before a webcam and wave twice, just before carving a turn, no doubt, on “packed powder” conditions.

Jeff Wozer (www.jeffwozer.com) works as a nationally touring stand-up comedian based out of a secluded perch in the Rocky Mountains.