Joint Venture

All about the ACL.

Kevin was excited, and if he was honest with himself, more than a little nervous. This was his first time. All of his friends had done it, some of them more than once. He wasn’t positive about Ben, who said he’d done it with a girlfriend from Canada when none of the gang was around, but everyone else gave pretty solid accounts; a couple even caught the act on video. Kevin took a deep breath, looked down, and decided to give it a go. He dropped in smoothly off the lip and turned toward Flippers for the first time.

The first huck was about a 10-footer, but he went just a little too big, and landed flat. Kevin’s left binding released but the right one didn’t. He felt a pop in his right knee. He took a physical inventory, went to stand up, but couldn’t bear weight. As he sat in the snow and waited for ski patrol to help him down, he thought that maybe ditching skiing and hooking up with his girlfriend—as she had suggested—might have been a little safer.

Kevin experienced what many skiers do: an acute ACL injury. During the ski season, we will see this sequence over and over: fall, pop, inability to ski down, and swelling in the knee over the next 24-48 hours. ACL injuries are extremely common in the U.S., occurring approximately 200,000 times a year and leading to 140,000 surgical reconstructions.

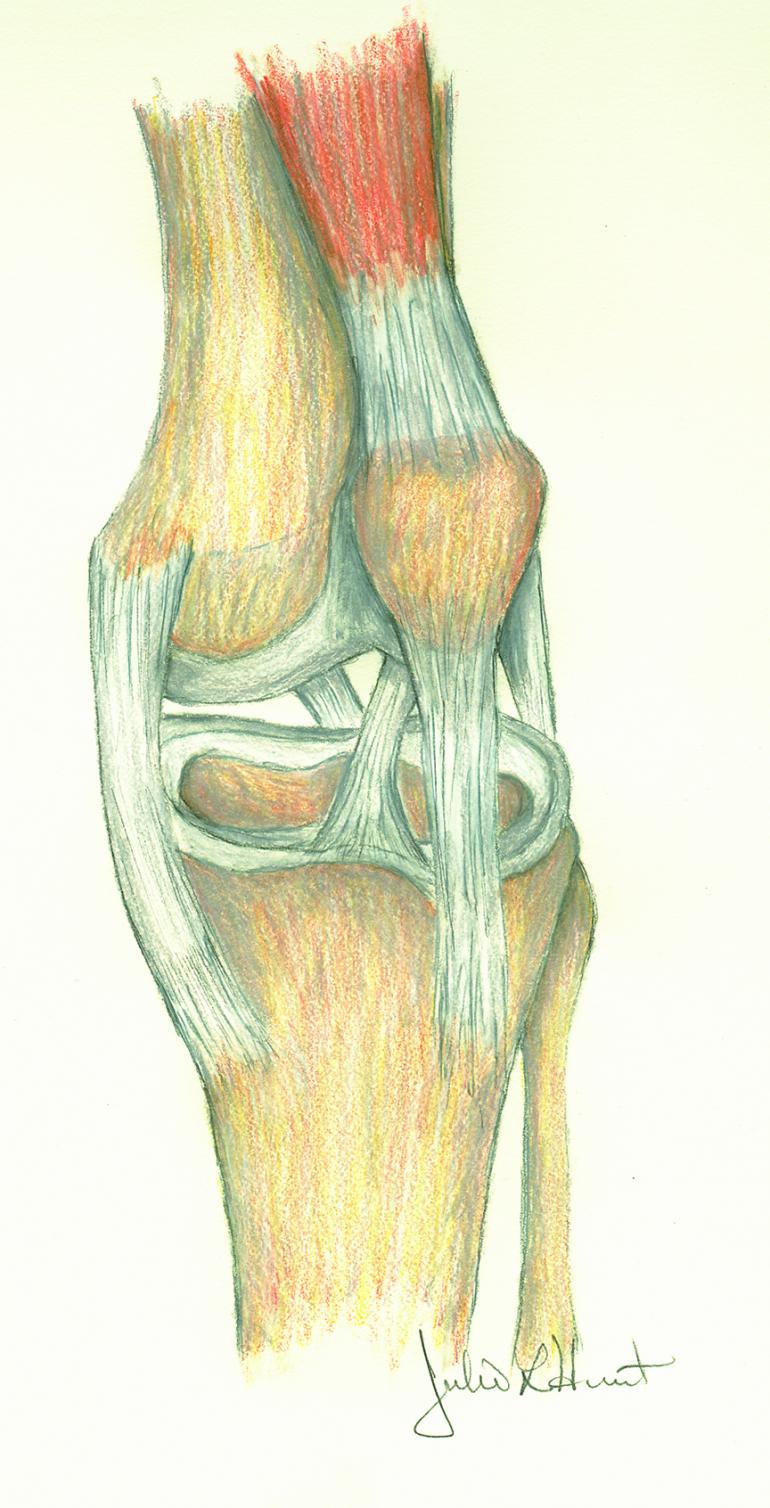

The ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) is one of the main stabilizing ligaments in the knee, controlling both translation and rotation. Unfortunately, the ACL has essentially no potential for healing and once torn, won’t regenerate. When the ACL is injured, other structures (most commonly the menisci) are injured around 30% of the time.

An experienced orthopedic surgeon can usually diagnosis an ACL injury based on patient history, a physical exam, and (normal) x-rays. In difficult cases, or instances of further structural damaged, an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) can help confirm the diagnosis. Physical therapy is most likely your next step toward regaining motion and resolving any swelling.

Patients can manage ACL injuries either by toning down their physical activity, or with surgery. Non-operative treatment consists of therapy to improve balance and strength, in addition to avoiding high-risk activities. For some patients, an ACL-substituting brace can provide enough stability to resume their typical activities.

Generally, the older and less active a patient, the more likely non-operative treatment is to be successful. When your goal is to be able to sit on a barstool, drink beer, and watch golf—as one of my patients once stated—successful non-operative treatment is almost assured. With younger, more active patients, we recommend surgery. With successful surgery, a patient is more likely to resume all activities, including higher-risk activities such as aggressive skiing, biking, climbing, and running.

Despite the high success rates of surgery, the holy grail of sports medicine remains ACL injury prevention. A disproportionate number of ski-related ACL injuries occur later in the day when legs are presumably tired. Although there is little hard data to support it, a prudent ACL prevention program would be to enter the ski season in good shape and avoid skiing late into the day when quads are burnt out.

As ski season approaches, it’s great to be excited but even better to be smart. Get yourself and your gear in good shape and make good decisions on the hill. I hope you all have wonderful seasons without injury—but if things do go wrong, see your orthopedic surgeon and together, make a plan to get back to all the fun things Bozeman offers.

Alex LeGrand is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon, fellowship-trained in Sports Medicine. He is an active US ski and snowboard physician and is the head team physician for MSU. He practices at Bridger Orthopedics and Sports Medicine.