Denim Diaries

Before skiing was a scene, people skied in jeans.

The man who taught me how to ski was a child of the Rockies himself, born in the shadow of 14,000-foot peaks, helping his family scratch a living from serving the whims of the few tourists who could afford a vacation during the Great Depression.

His ski hill lay just outside town, a one-run affair with a rope-tow through the alpine fir where he learned the art of the tele-turn long before it was called that. He thought he was pretty cool on those long wooden skis, strapped to his feet by what he called “bear-trap” leather bindings. Those skis now hang up in my office as wall decorations, an ode to the Rockies, to my dad, and another era.

In the 1950s, he was drafted into the Korean conflict, but fortunately ended up working as an eye doctor in a hospital in Germany, the same hospital where a decade before, General George Patton died. There he skied the legendary runs where Germany, Italy, and Austria mash together as the Alps.

By the time he was brave enough to take me and my brother skiing, he was back in the Rockies with an optometry practice, a home in the pines, minutes from the ski slopes. Every weekend we piled into our 1958 Chevrolet Apache, one of the country’s very first mass-produced four-wheel drives—and drove to the ski hill. The slopes were not a lot different from those of Dad’s days, just a few long runs in the timber, a T-bar lift, and a lodge that smelled of woodsmoke, burger grease, and wet wool. Everyone knew everybody, and in fact, my best friend’s dad managed the ski slope.

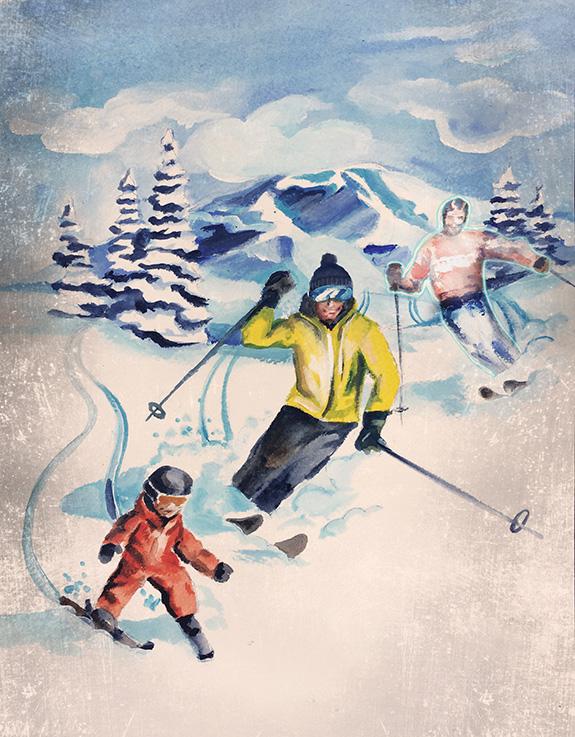

When you are four or five, everything has a different angle to it. The runs are steeper, the skis longer, the teachers taller. My dad had a quiet way about him, a patient teacher to a petulant student who fell often and found words that few young children know, much less utter. I wore a snowsuit of some kind and for good reason, for I was often covered from top to bottom with snow. There were no leashes for Dad to slow the student, no helmets, no safety harnesses. Instead it was strap-it-down-and-go, demonstrate a few moves, turn it loose. The skis were wooden with metal edges honed by a file, the boots leather.

Viewed through the long backward lens of time, I am pretty damned certain I was a little shit and a piss-poor student. But eventually, after many trips to the ski slope, after peer pressure—my buddy whose dad ran the hill had no choice but to ski every weekend—I began to look forward to it. By the mid-1970s, we’d upgraded the vehicle to an International Travelall—a bright-yellow gas-hog that Dad called the “Corn Binder”—and upgraded the skis to fiberglass.

We took on bigger hills too, like Lone Mountain. The lodges still smelled of wet wool and burger-splatter, but the runs were longer and somehow colder. Still, Dad hung in there and taught us a few moves and we learned how to stem christie like Dad did, swooping long runs that were graceful and a thing of beauty. He had upgraded out of the bear-trap bindings, but still rode ridiculously long skis well up over 200 centimeters in length and narrow as a butter knife. They were red and white and some kind of lacquered wood-fiberglass composite.

I’m not exactly sure when skiing became a “scene.” But for a long time, it was just about families and fun. Most of the cars in the parking lot were American gas-guzzlers with rear-wheel drive and tire chains in the trunk. Skis also went in the trunk, or were jammed inside with the passengers.

On the slopes, it wasn’t a show, it was about getting as many runs in as you could while the sun was up. Learning was by doing and there was much less thought about safety. There were no helmets still and the bindings were supposed to be quick-release if you fell, but they hardly ever did. I skied in jeans and wore a sheepskin-lined Levi’s jacket. I felt pretty cool. By this time, I had pretty much ditched Dad, who was content skiing with friends his own age.

When I was finally able to get on the mountain by myself, it was with all my high-school buddies crammed into my 1969 Camaro. We prided ourselves on being the first on the lift and last off the mountain. We still skied in jeans and our skis were still long. Long skis were in vogue and some runs even had length restrictions. Snowboards had not even been invented and tele-turners were rare.

Occasionally, I still skied with Dad. Skiing was at its peak in the late 1970s and early 1980s and I skied all the time. Although I went to college in the desert, I brought pals home by the truckload for Christmas and spring breaks. Dad and I got out a few times too, but mostly, he was content to stay home. When I dropped out of school to be a ski bum in Jackson one winter—a fortuitous move that coincided with the heaviest snowfall the Rockies had ever seen before or since—he was livid and we argued. But eventually I went back to college and all was forgiven.

These days, I find myself on the slopes with my daughter, giving lessons just like my Dad did. I hope I’m as gentle and patient as he was; it’s a worthy goal. She, certainly, is a much kinder student than I was. I head for those quaint family places around Montana that remind me of Dad. They are found on mountain ranges in the Big Belts or the Pioneers, places where the lodges smell of wet wool and burger grease. She wears a helmet and goes down what she calls “the rabbit slopes” and up the magic-carpet lift and back down again. There’s barely enough slope to get going, but she has fun and laughs a lot. We get in as many runs as we can. Sometimes, I see someone wearing blue jeans.

Tom Reed is the author of several books, including Blue Lines, A Fishing Life. He lives with his family on a small ranch outside Pony.