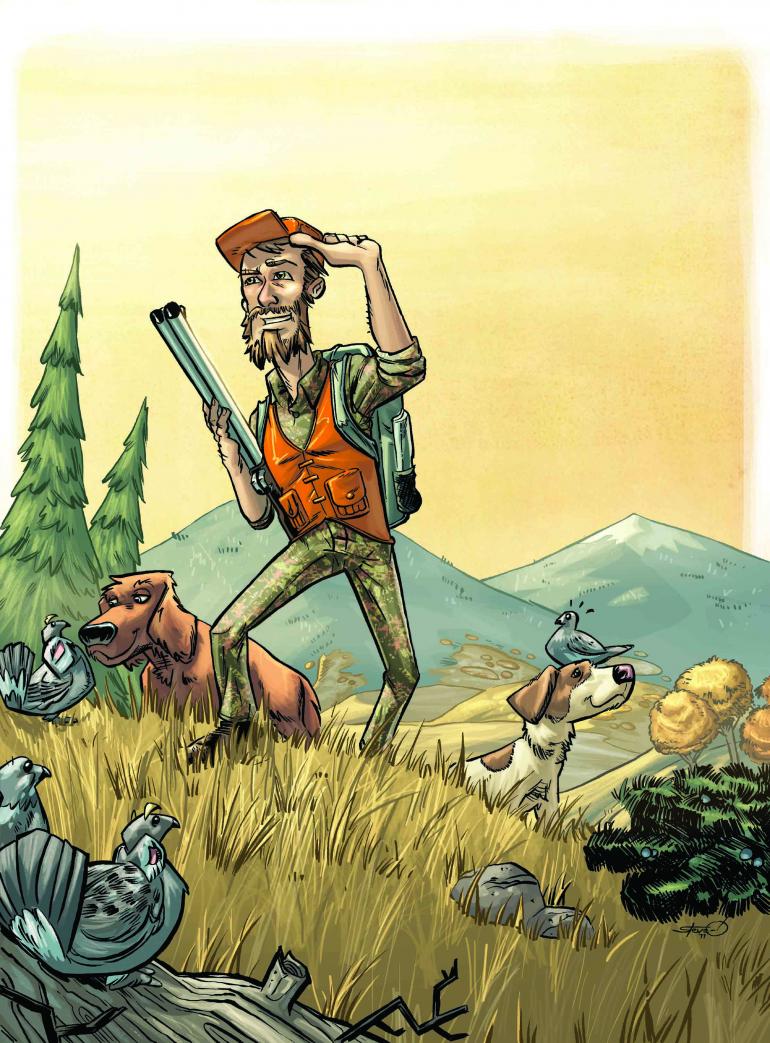

Grouse of a Different Color

The best-tasting, least hunted gamebird in Montana.

The dog, Powder, found the brood in an open meadow at 6,500 feet in elevation—1,500 painful feet higher than where we’d left my truck. They had scattered out below a lonely and ancient Douglas fir, where they’d undoubtedly spent the morning looking for grasshoppers. Powder pointed, and when the first bird flushed from under my friend John’s feet, it promptly flew into a tree.

Blue grouse do that. Not always, but often enough that if there’s a tree around, you can be reasonably sure they’ll make a run for it. That bird was followed by another, then another, until—like chickens in a row—there were six or seven of them sitting on a limb 30 feet above our heads. Powder, who has been (somewhat) trained to be steady (most of the time), managed to stand her ground—but just barely. The birds clucked to themselves and watched her. Powder’s amber eyes bulged.

There are two ways to dislodge a sitting grouse: shoot it, or throw a stick at it and then shoot it. Tree-flushing grouse almost always fly downhill, and because I’d been through this before but my buddy hadn’t, I generously offered to stand downhill and shoot at any birds he dislodged. I even offered to find him a stick.

Turns out John doesn’t have much of a throwing arm. By the time he actually got one of the birds to move, he’d pretty much cleared the area of lumber and had to resort to breaking the lower limbs off the tree. Finally, as yet another of John’s sticks flew wide of the mark, one of the birds craned its neck for a look, sidled forward a few inches, and launched itself into the wild blue Montana yonder. I shot, and the bird tumbled downhill 75 yards and rolled gently to a stop. This was noteworthy primarily because I would not make a similarly good shot for a long, long time. In fact, it had been a long, long time since I’d made a good shot prior to that one. You can’t say I’m not consistent.

Bow hunters take far more grouse each fall than shotgun hunters do. Besides being shish-kebabed by arrows, they’re whacked with 30-06s and dispatched with .22 pistols. Only rarely are they pursued with bird dogs and honest-to-God shotguns—which suits me just fine. Last time I counted grouse hunters, I couldn’t get past the fingers on one hand. When you consider the millions of acres of public forests in the state, the competition is spread pretty thin.

The main reason is that hunting blue grouse is hard work. Not hard in the sense of being hard to find—their habitat isn’t difficult to recognize—but hard in the sense of being difficult to get to. The suicidally trusting road birds, of which there are considerable numbers early on, don’t last much past the first week of the season. After that, you’ll have to go looking for them. And no matter how far up you drive before you start, the grouse will always be above you. Way above you.

A big blue shows its true colors

For the last few years I’ve kept not-particularly-scientific tabs on where I flushed birds, and I have found, courtesy of my GPS, that I start seeing them at about 6,500 feet. Yes, I’ve found them at lower and higher elevations—one ridgeline I hunt is above 8,000 feet—but between 6,500 and 7,500 feet seems to be prime, at least in southwestern Montana. Although the birds spend their summers in the foothills, they apparently move up into the mountains quickly around the end of August. One friend of mine—a guide who knows what he’s talking about—finds blues in the foothills early in the season, but that’s never happened to me.

An indicator that you’re at the right elevation—you’ll have to excuse my skimpy botanical background here—is a kind of low-growing juniper that usually encircles the base of old-growth conifers like wreaths. The shrubs don’t seem to play a part in the bird’s ecology, but they do seem to grow at the same elevations where I find grouse. Once I have either of those indicators—a reading on my GPS of 6,500 feet or the low-growing junipers—I begin looking for specific habitat. Open meadows surrounded by old-growth conifers are prime. Over the years, I’ve heard theories that grouse like the south sides of east-west running ridgelines, and they do—but they also like the other sides, too. In my experience, the way the slope faces doesn’t have much bearing on whether I find birds. Locate a meadow with snowberry bushes and grasshoppers, and you’ll be in grouse country.

In fact, I spent several years hunting nothing but open meadows and ridgelines, my dogs and I walking logging roads from one opening to the next. Then, a couple seasons ago, I discovered clear-cuts. I don’t know why it took me so long to figure them out; clear-cuts, after all, are man-made meadows, and many grow snowberries, green forbs, Oregon grape, and the other tasty things blue grouse love. Older clear-cuts surrounded by mature timber are best; look for the birds either along the edges of the old growth or, conversely, near patches of regenerating pine saplings. And keep your wits about you. A blue grouse flushing through dense, head-high saplings is every bit as difficult to hit as its more storied cousin, the ruffed grouse.

Because I hunt grouse exclusively with dogs, I like to be in the mountains first thing in the morning, when it’s cool and the dogs have a better chance of scenting a brood of feeding birds. I also know of people who hunt late in the afternoon and do pretty well, too. But I like to pull my dogs out of the woods around 10am or so, before it really starts warming up. Running up and down hills and hurtling over deadfalls is brutally hard work for any dog, and even temperatures of 60 degrees are warmer than I’d like. Needless to say, your dog should be in good condition before the season begins. Don’t count on ”hunting” your dog into shape; my dogs—who are typically in good to excellent condition by the grouse opener—have pulled muscles, torn up pads, and nearly collapsed from hypoglycemia as a result of hunting in that vertical country.

Most of my hunts are two or three hours long, but at least some of that time is used up getting to where I want to go. A few years ago, John and I spent about an hour hiking to a ridgeline, a trip we make two or three times every season. The place is worth the walk. We follow a logging road that rises gently on the way in, and by the time we reach the base of the ridge, it’s just a few hundred yards of climbing to get to the top.

It’s perfect grouse habitat. Meadows and glades are strung together like pearls on a string, and one side of the ridge drops off sharply into dense, black timber. Typically, the birds perch on the edge of the drop-off or venture a few dozen yards into the meadows, then bail over the side after they flush. That day grouse were everywhere.

My dogs pointed a few of them on the ground, but most were sitting in treetops watching us walk by. Invariably, they’d explode out of the limbs 60 feet above us and hurtle toward the valley below, careening through the trees like little blue jets, complete with sound effects. We sent them on their way with a fusillade of pointless shots. After flushing around 18 or 20 birds, Scarlet, my setter, finally stuck a single on the edge of a meadow above us, and the startled grouse flew over her head and directly back toward John and me. It was too much for my little setter, who had been stopping in her tracks at the sound of flushing grouse all morning. She took off after it, and when it was a few yards from John, she had almost closed the gap.

The bird flew so close to John’s head that he actually had to back away from it, but he brought his gun up as the bird passed, Scarlet much too close for comfort. Then, in a moment of clear-headedness I’ll always be thankful for, he pulled up his gun and the shot rattled harmlessly into the trees. No grouse is worth the life of a dog.

The birds can be a bit unsettling for an inexperienced dog, however. Despite the moderately thin cover of most meadows, blue grouse often make little attempt to hide, and may tiptoe around in front of your pooch like a clutch of nervous chickens. It takes a dog with nerves of steel not to break and take out the lot of them.

Blue grouse hunting is not a sport for the marginally enthusiastic. I know of no place—and there are a lot of places I hunt—where I can simply step out of my car and begin hunting. The few grouse I manage to kill each year are rarely near roads, although even I get lucky once in a while. A few ago I got a call from the Chronicle. Seems the outdoor editor wanted some photos of bird hunters, and I was the bird hunter he happened to know. I gave him my usual spiel about making sure he sent somebody who could keep up, wouldn’t complain about climbing mountains, blah blah blah. The photographer he sent, a woman, was a former member of the MSU track team and a long-distance runner, with maybe—I’m guessing here—six percent body fat. She looked like she could run up a mountain backwards.

By the end of the day, she had. After explaining to her that it was a long hike into one of my favorite ridgelines, and allowing as how we probably wouldn’t see many birds, grouse are just that way, etc., we drove to my usual parking spot. I pulled to a stop, and suddenly there were birds everywhere.

The first flew across my windshield while I sat behind the wheel gaping in astonishment. I gathered my wits enough to bail out and run to the back of the truck, where John and I began throwing on vests, yanking guns out of cases, and loosing the dogs. A minute later we marched down toward where we’d seen the grouse go, only to put up several more birds on the way. Grouse were flushing everywhere, most of them before Powder could establish a point. The photographer, meanwhile, was back-pedaling furiously ahead of us, snapping photos. Half a dozen shots later, we’d yet to cut a feather.

By the end of the morning, we’d put up 16 birds in singles, pairs, and broods, and in keeping with long-standing personal tradition, I had missed every shot I’d taken. John and I finally—finally—scored on birds a few minutes apart as we trudged, footsore and deflated, back to the truck. The photographer snapped Powder’s picture with the grouse in her mouth, and a few days later she was splashed across the sports section of the Chronicle in living color.

Days like that do not in the least diminish my enthusiasm for hunting blues. Standing on top of a mountain with no one else within miles gives me hope for a sport that will never be subject to bidding wars over leased land. It’s mine—all of it—as far as I can see. All I’ve got to do is find the birds. I’ll work on my shooting later.

Author Dave Carty is a dedicated blue-grouse hunter and spends most of the month of September chasing them. This story first appeared in Montana Sporting Journal.

Grouse Guidelines

Taking your gun for a hike, as many experienced grouse hunters call it, is one of the great pleasures of a Montana fall—whether you see a bird or not, you still had a nice hike through the autumn woods. Mountain grouse season—which includes blue, spruce, and ruffed grouse—generally begins September 1 and ends January 1. Bag limit is three per day. While you can certainly bag a few birds on your own, it’s best to bring some sort of canine assistance along, even it if it’s not a trained hunter—the dog’s energy and nasal power alone will allow you cover exponentially more ground and get way more birds in the air. —Mike England