Ducks in a Row

The history behind the federal duck stamp.

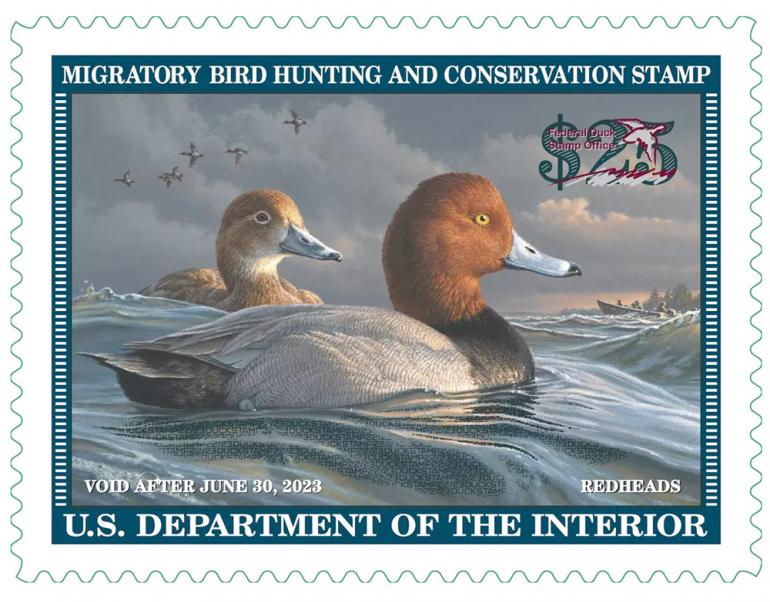

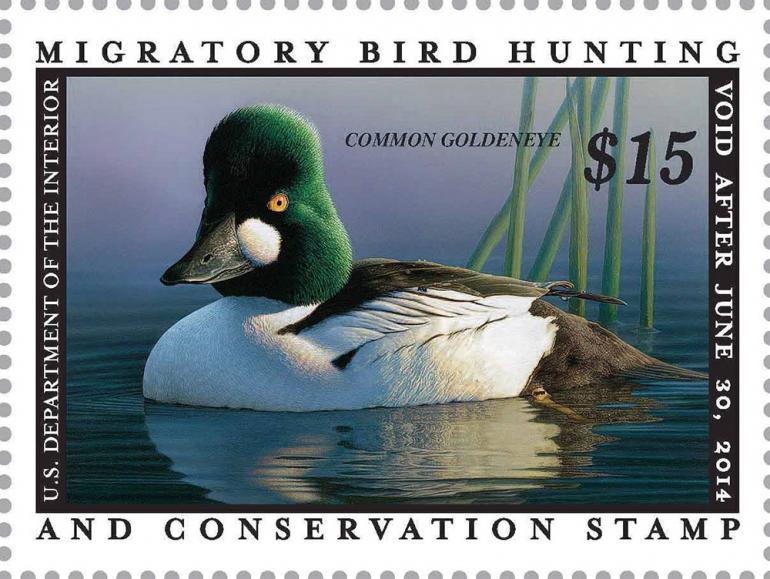

The Duck Stamp Act, more formally coined the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act, requires waterfowl hunters 16 years old and older to buy and carry a federal stamp every year when hunting migratory waterfowl—such as northern pintails, mallards, Canadian geese, and snow geese. It serves as a hunting license, but also a ticket into any national wildlife refuge requiring an entry fee. While mandatory for hunters, the stamp is also available to anyone interested in contributing to conservation efforts.

In the early 1900s, excessive development for both agriculture and urbanization purposes were destroying wetlands and threatening numerous bird populations. To combat the destruction, the Duck Stamp Act was established in 1934, and since has been used to fund the conservation and acquisition of wetland habitats essential for migratory birds.

The money raised from stamp sales has gone toward the acquisition of over six million acres of upland and wetland habitats across the country.

In today’s economy, the stamp costs 29 bucks ($25 dollars for the stamp itself, and a $4 processing fee). Ninety-eight percent of the revenue assists in purchasing conservation easements for the National Wildlife Refuge System, and helping to acquire and preserve wetland habitat. Wetlands purchased with the funding contribute to the improvement of outdoor recreation opportunities, water purification, and flood control; and reduce the risk of soil and sediment erosion. The money raised from stamp sales has gone toward the acquisition of over six million acres of upland and wetland habitats across the country. During migration, these lands are vital locations for waterfowl and other wildlife to nest, feed, and rest.

Originally intended to be a simple conservation tool, the Duck Stamp Act has expanded over time to become a comprehensive environmental program. The stamp provides safeguards for the National Wildlife Refuge System’s funding, and has grown into an international partnership by contributing to initiatives in conjunction with Mexico and Canada.

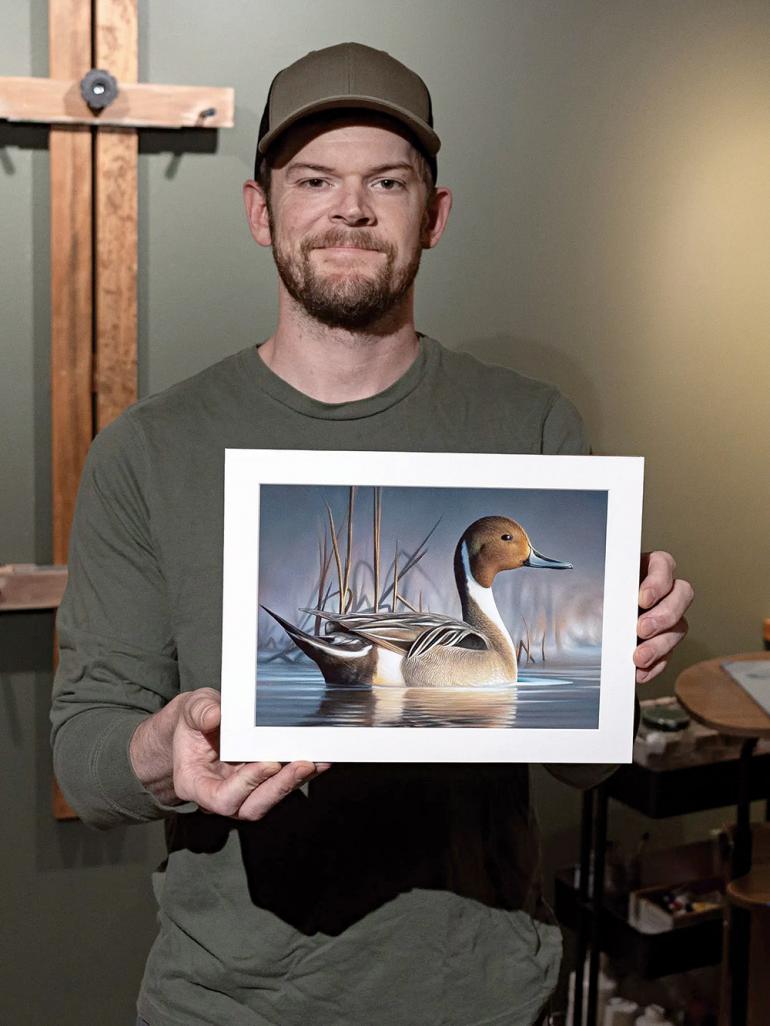

As for who designs the stamps, an annual art competition is conducted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (which happens to be the only federally-sponsored, juried art competition in America). Any artist at least 18 years old is eligible to enter, and the winner gets his or her creation on the Federal Duck Stamp for the upcoming year. Belgrade-based artist, Chuck Black, won the 2023 contest with his oil painting of a drake pintail—his entry being one of 198. His work can be seen on the 2024-2025 duck stamp. The state of Montana has a separate art competition for a state waterfowl stamp, which comes with the purchase of a state hunting license.

Since its enactment 90 years ago, the Duck Stamp Act has played a pivotal role in wildlife preservation, serving as an example of how targeted conservation and policy efforts can be used to upkeep environmental stewardship. What began as a simple policy has now developed into a complex program with wide-ranging benefits—and hopefully will continue to do so for many generations to come. After all, it’s up to us to protect the creatures who cannot speak up for themselves.

Editor's Note: Put the Lead to Bed

In 1991, the federal government banned the use of lead shot for waterfowl hunting. This restriction has been a huge help for our aquatic ecosystems, so why not expand it to all shotgun hunting? The status quo is that it’s acceptable for hunters to spray lead shot into meadows and hillsides harboring grouse, pheasant, and turkeys, but not okay to shoot the stuff at ducks and geese just down the hill at water’s edge. What’s the distinction? Where’s the line? Lead is lead, and it’s toxic to animals no matter where it’s discharged. This fall and winter, keep our local waterways and hills clean by switching to steel or other lead-free shot. It’s readily available, equally as effective, and only slightly more expensive. What are you waiting for?