The High Life

One man’s 40-year quest to bag Greater Yellowstone’s highest peaks.

Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you like sunshine into trees. —John Muir

It’s late July and I’m perched atop Mount Fitzpatrick, 10,907 feet high in the Wyoming sky. I’m filled with gratitude, wonder, relief, and joy, for I have just completed the most challenging project of my life. Fitzpatrick, like many of the mountains I have climbed, is the highpoint of an entire mountain range—in this case the Salt Rivers. It’s the last stop on a long peak-bagging journey that began in 1982.

Peak-bagging is nothing new. There are lots of challenging high-point lists: all the 4,000-footers in New England or the Adirondacks; all the 14,000-foot peaks in Colorado; the high points of the 50 states; the Seven Summits of the continents; or all the 8,000-meter peaks in the world.

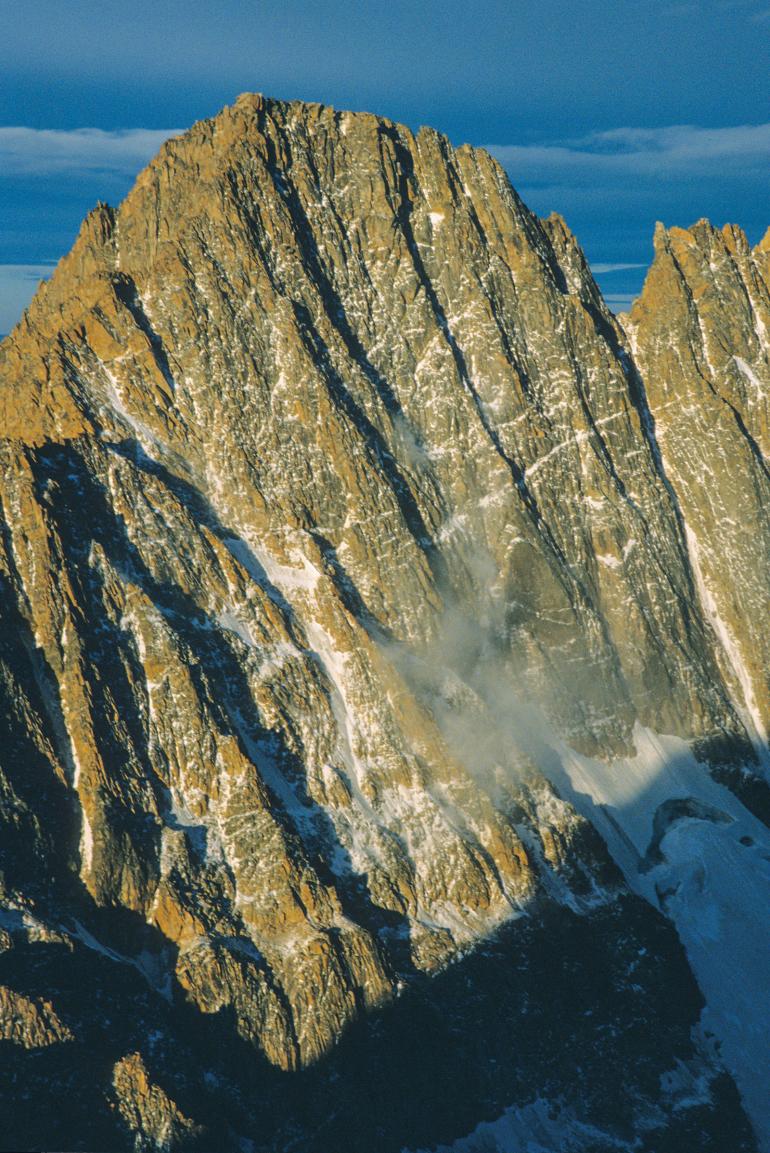

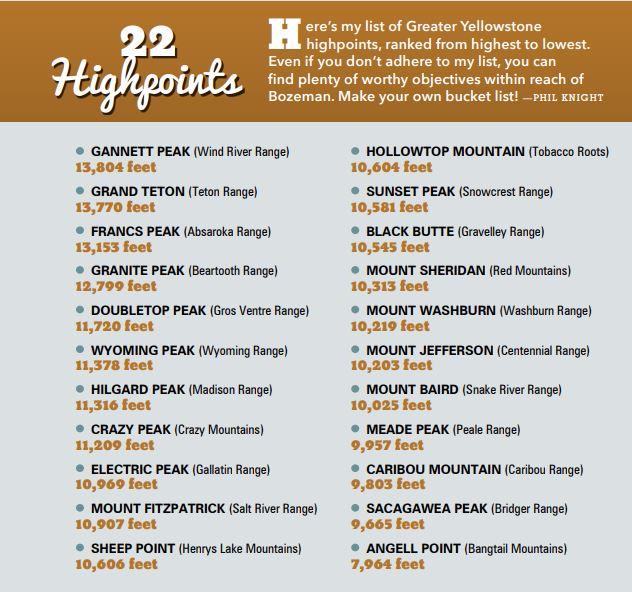

I made my own list. In the summer of 2010, I set a goal to climb the highest mountain in each of the 22 ranges of Greater Yellowstone. No one had done it before, to my knowledge. And at the time, I was already more than halfway there. I had just summited one of the hardest—and certainly the highest—peaks in all of Greater Yellowstone. Gannett Peak, the Wind River Range’s apex at 13,804 feet, required a five-day trip with a 20-mile approach and roped climbing on glaciers. It was the only peak in the Rockies that I climbed with a guided group.

The rewards of mountaineering, however, are immense. You develop your body, your skills, and your self-confidence.

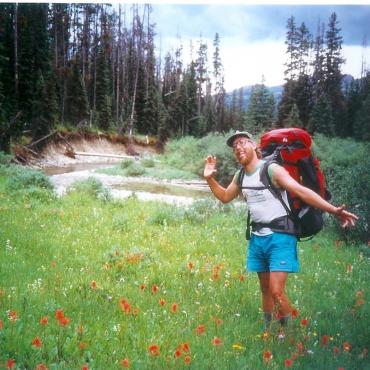

The northern Rocky Mountains are not to be underestimated. Greater Yellowstone mountains are formidable and some of the peaks, like Gannett, are quite remote. The surrounding countryside is populated with mythically ferocious beasts like wolverines, moose, mountain lions, and grizzly bears. The terrain is convoluted, confusing, and at times impassable. During a Yellowstone mountain adventure, you may have to cross raging creeks, bushwhack though dense blowdown, scramble on chossy cliffs, dodge lightning storms, lose your bearings, pick the wrong way down, bivouac in an exposed location, be charged by a moose, or run out of food. If you go at it solo, as I often have, you enter another realm of independence and challenge.

The rewards of mountaineering, however, are immense. You develop your body, your skills, and your self-confidence. You amass a trove of campfire stories. You are literally getting the lay of the land. You are engaging in an age-old human pursuit of exploring under your own power, using your wits and your strength. You are learning what exactly to bring and what not to bring. And that post-climb beer never tasted so good.

I owe much of the inspiration for my Greater Yellowstone highpoints project to a classic book called Select Peaks of Greater Yellowstone by Thomas Turiano. Select Peaks lists 107 mountains in 15 ranges or sub-ranges across the Yellowstone Ecosystem, describing climbing routes, history, first ascents, ski descents, and other factoids along with sharp black-and-white images of the mountains. Turiano is a true mountaineer, much more accomplished than I, and has climbed every mountain in his book!

For my own list, I added several outlying mountain ranges to Turiano’s list, resulting in 22 peaks in 22 ranges. But make your own list. Climb as many mountains as you like. Do it for the sheer hell of it—because you can. These are my most memorable:

Electric Peak

My first highpoint was Electric Peak, at 10,969 feet. It’s the apex of the Gallatin Range, and I climbed it during my first summer out West, 1982, having no clue that this would become a bit of an obsession later in life—I didn’t even realize that Electric is the high point of the Gallatin Range.

Electric is a must-do for any Yellowstone backpacker. Named by three surveyors who climbed the peak in 1872 and were nearly struck by—you guessed it, lightning—Electric is a class act. Viewed from Gardiner, it rises 6,000 feet to a classic pointed summit with a steep, complex northeast face split by rugged ridges.

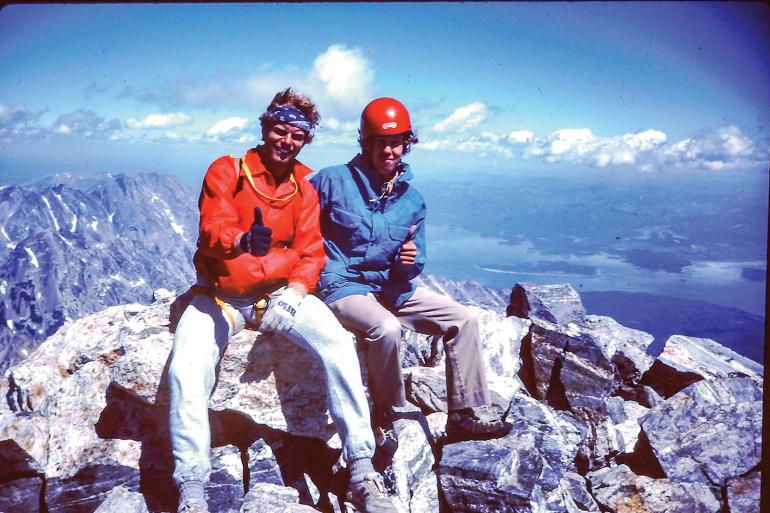

Grand Teton

I tagged one of the hardest and highest summits on my list in 1982 also—a real plum prize, the Grand Teton. At 13,770 feet, this iconic spire is the second-highest peak in Greater Yellowstone and the apex of Grand Teton National Park. This mountain draws climbers from all over the world, and most use ropes for protection and descent. I climbed this incredible peak with Robert McDermott, a friend from Kentucky. We tackled the exposed ridge of the Upper Exum route. As the more-experienced rock climber, I led the whole climb. We stupidly brought only one rope and had to team up with another party for the long rappel off the summit.

Sacagawea Peak

You don’t have to venture more than a few hours from Bozeman to reach a lot of the highpoints. Any Bozeman hiker worth his or her salt has hiked Sacagawea, queen of the Bridger Range at 9,665 feet. She can be reached via a five-mile round-trip hike from Fairy Lake. Try tagging Hardscrabble, two peaks to the north, while you’re at it.

Hollowtop Mountain

A little further afield, but still visible from Bozeman, is Hollowtop Mountain at 10,604 feet in the Tobacco Roots. It’s a wonderful, friendly summit, climbable from Skytop Lake or from the South Boulder River. When my nephew Torin climbed it, he was surprised to meet a school group of five-year-olds on top! I have climbed it three times and skied off the summit down the obvious snowfield—the “hollow top”—and into a steep couloir below that.

Crazy Peak

Crazy Peak, at 11,209 feet, is a challenging one. Climbing the endless talus from Blue Lake, you eventually find yourself on a false summit. To reach the actual peak you must then descend a steep gully, and work your way around two prominent rock towers before climbing the summit block to the top. Then you must reverse all those moves.

Crazy Peak also has the awkward distinction of a privately-owned summit. That’s right, you may be trespassing if you tag the summit. It’s probably possible to get permission to climb it, but I’ll leave that up to you.

Granite Peak

The most stubborn peak on my list was the infamous Granite, Montana’s apex at 12,799 feet. The lofty top of the Beartooth Mountains, Granite is a major objective for any Montana mountaineer and for climbers from around the country. It’s considered to be one of the most difficult state highpoints, after Alaska’s Denali but equally hard as Gannett Peak in Wyoming or Mount Rainier in Washington. Remote and storm-raked, steep and intimidating, Granite demands skill, planning, and respect. And in my case, persistence.

I first tried Granite in 1993 with friends from work. We started from West Rosebud Trailhead and hammered out the endless switchbacks to the Froze to Death Plateau. Then it was another five miles with big packs, higher and higher up the plateau until we could see the summit of Granite peeking over the shoulder of Tempest Mountain. Finally we set our tents at about 11,700 feet on the windswept, exposed tundra.

Unfortunately, the weather gods were not with us. We woke to an August snowstorm coating everything with wet snow and rime ice. We threw everything in our packs and turned tail for home.

1994 brought similar results when I went with a different group of friends. This time we started from East Rosebud via the Phantom Creek Trail, a slightly less steep approach. The mountain goats were glad to see us—they hang out near camping areas and wait for people to pee so they can lick up the salt.

Again, we were hit with an August snowstorm overnight, and Granite Peak was out of the question. This time we did manage to tag the summit of Tempest Mountain, catching glimpses of a very wintry-looking Granite Peak. Would I ever get up there?

Finally, the fates were kind to me on my third attempt on Granite, in 1995. Brian “Bird” Morris and I trekked in via the Phantom Creek Trail and on up to Froze to Death. With good weather I led three short, fun pitches of rock climbing on the way up the East Ridge. By mid-morning we had topped out on the wide, flat summit rocks and high-fived on the top of Montana.

Black Butte

Well within reach of Bozeman for a summer day-trip is the top of the Gravelly Range—Black Butte. At 10,545 feet, it’s no slouch, but a scenic drive makes it quite accessible. Start in Ennis and drive the north end of the Gravelly Range Road 38 miles to near Black Butte. Park along the dirt road, make the two-mile hike, and scramble to Black Butte’s rocky summit for a vast view across the Gravelly, Snowcrest, Tobacco Root, and Centennial ranges. Camp atop the Gravellys or make your way back to Ennis for dinner. Or do as I did and drive home to Bozeman, happy in your highpoint euphoria.

Mount Washburn

On the bucket list for any Yellowstone hiker, Mount Washburn at 10,219 feet is the highpoint of the mountain range by the same name. Washburn is probably the easiest 10,000-foot peak in the entire Yellowstone ecosystem. The trail is three miles long and climbs about 1,200 feet from a choice of two different trailheads.

I climbed Washburn for the first time in 1982, on a June day. Much of the trail was covered in huge drifts of hard-packed snow. On top is a fire lookout tower. The lower two floors are open to hikers, providing a welcome refuge from bad weather and the constant winds.

Washburn is located in the north-central part of the Park and provides sweeping panoramic views across the Beartooth and Absaroka ranges, the Tetons, the Red Mountains, Yellowstone Lake, and the Gallatin Range.

Hilgard Peak

One of Montana’s most spectacular mountain ranges, and its second highest, is the Madison Range. The Taylor-Hilgard peaks in the southern part of the Madisons are world-class wilderness with a rugged jumble of steep, colorful limestone mountains and darker, more foreboding igneous peaks sprinkled with jewel-like lakes and rushing creeks.

Topping the range is Hilgard Peak at 11,316 feet. It’s a stunning, remote double summit. I had admired Hilgard and lusted for its summit ever since my first trip into the Hilgard Basin in 1986.

Hilgard Peak was not climbed until 1948, when Dave Wessel climbed it in one day, for a solo first ascent of a major Montana summit. My mountain-man friend Joe Gutkoski was the first to climb Hilgard in winter, in 1977 with climbing pioneer Barry Frost.

In 2011, with my friends Todd and Ted, I drove to the Potomageton Park trailhead at the south end of the Madison Range. We headed up the trail toward Blue Danube Lake, then peeled off to Avalanche Lake. It was Labor Day weekend and the weather was clear and cool. At Avalanche, we had to find a way to reach the base of Hilgard, to the north.

At 10,500 feet we bivouacked near a small tarn. Hilgard Peak’s spire rose just above us in an intimidating 700-foot-high wall of steep, loose rock, with no obvious route.

We woke at dawn to find our sleeping bags covered with thick frost. It was a fairly short climb, but tricky, and very steep. We persevered and soon found ourselves on the summit ridge. We made the summit by 8:30am in true alpine style, and snapped some photos. We took in the wide sweeping views of the rugged ranges around us. Damn. Ear-to-ear grins split our faces. Top of the Madisons!