Pining for Rock

Geology along the Pine Creek trail.

Numerous hikes are just outside the door, but a combination of alpine views steeped in multiple layers of geologic time is hard to beat. Perfect for a daylong activity with a friend, Pine Creek is also great for priming your summer trail legs. Gaining 3,400 feet elevation in just four miles (creek crossings to boot), this hike is more than just a simple walk, so be prepared! Grab plenty of water, snacks, a good map, and proper attire for that summer afternoon thunderstorm. Also: pack it in, pack it out.

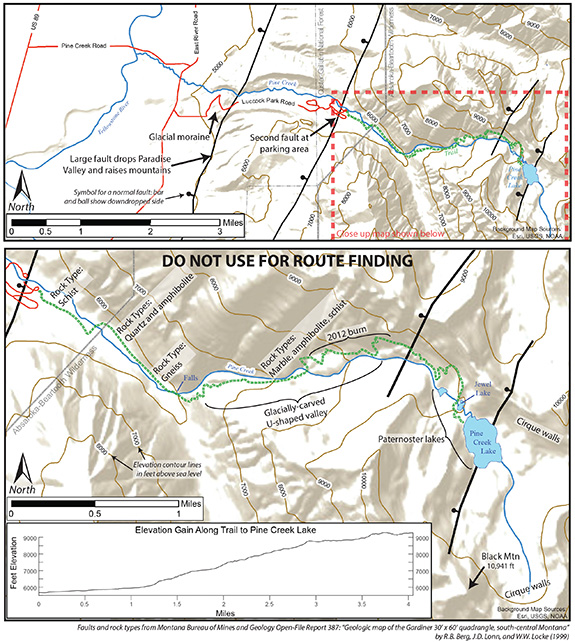

Your geologic story begins before the trail. Driving up Luccock Park Rd., you pass around a large hill. This is a moraine, where a glacier from high up the Pine Creek drainage stopped in its tracks and piled up sediment like a bulldozer. From here, you leave the valley behind and enter the mountains. This sharp change in topography all along the mountain front is caused by faults that down-dropped Paradise Valley and uplifted the mountains. Another fault lies beneath your feet in the parking area. The valley floor has dropped over 10,000 feet relative to the mountains, and based on scarps near Yankee Jim Canyon, they are no stranger to recent earthquake-forming rupture.

Thanks to these faults, though, you have access to very old rocks. The resistant (difficult to erode) outcrops exposed along your hike are over 2.5 billion years old—over half the age of the Earth! The trail starts in schist, a dark rock rich in the mineral biotite (dark mica), and flaky in appearance. Once you hit the waterfall, you are standing in quartzite and amphibolite. Quartzite is light and rich in quartz; amphibolite is dark. The first switchbacks are in gneiss, a lighter-colored rock with a striped or banded appearance. Past the switchbacks, you are in a suite of rocks comprised of marble, amphibolite, and schist. You will be in this suite for the remainder of your hike, though slivers of quartzite are present, and you will also see boulders of gneiss eroded from the surrounding mountainsides.

These ancient rocks first arched up 74 million years ago from compression during a mountain-building event called the Laramide orogeny. Where you stand now forms a continuous range to Red Lodge: the Beartooth Mountains, though this part is commonly called the Absarokas among southwest Montanans. Geologists typically reserve “Absaroka” for volcanic mountains that formed after the Laramide, but long before Yellowstone. These volcanoes erupted rock all over the region, and make up Emigrant and Electric peaks. The Beartooths, partly covered by these volcanics, once continued toward Norris, but faulting since five million years ago has dissected the landscape into multiple ranges and exposed their deep interiors.

On the way up, you pass through the 2012 burn that destroyed homes in Paradise Valley. Years later, new vegetation is growing. Though common in the West, larger fires driven by consistently higher temperatures are beginning to threaten alpine flora and fauna. As fires burn old growth away, vegetation from lower elevations reclaim higher positions. It will be interesting to see what plants take root, and what animals are pushed to extinction. Pika are at risk due to their high-elevation lifestyle. Though somber, this shows we must remain vigilant for our wild landscapes.

Many vantage points offer views up and down the drainage. Notice its U-shaped character, the result of glaciers that carved these drainages over 10,000 years ago. In comparison, mountain valleys formed by rivers are V-shaped. You can use these simple criteria in virtually any high-mountain drainage to answer the question: water or ice? Before Jewel Lake, note the lake at the bottom of the cliff. Pine Creek Lake to Jewel Lake to this little lake forms a stair-stepping succession. Some call these paternoster lakes, like a succession of rosary beads. This type of geomorphology (landscape feature) is again evidence of past glaciers.

Arriving at Pine Creek Lake, note the semi-circle of cliffs surrounding you. These are known as cirque walls. Twelve thousand years ago, snowfall was accumulating here, but not melting seasonally. It then froze, compressed, and recrystallized, forming the glacier that flowed downstream. The tall peak is Black Mountain (10,941 feet), sculpted from the same suite of rocks with gneiss around its southern edges. Views from its top show the glacially carved range continuing to the southeast and Paradise Valley’s abrupt fault-dropped nature to the west.

Be sure to leave yourself plenty of daylight to get back to the trailhead and to note the geology once more. Indeed, this hike offers many glimpses into Earth’s history—recent and ancient—and a sense of appreciation for the tectonic and glacial processes responsible for the scenery.

Jacob Thacker is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of New Mexico.