Yellowstone to Yangtze

High on the Tibetan Plateau, the Yangtze River sits at an elevation of 12,000–14,000 feet; surrounding peaks tower at over 18,000 feet. Nomads still roam the region, and remote monasteries are commonplace. The location is so far off the grid that a joint study by the World Bank and the European Commission's Joint Research Centre recently named “the most remote place on earth.”

So when the Big Sky locals Eric and Brandy Ladd approached us about traveling over 8,000 miles to go on a rafting adventure in Tibet, it didn’t take much convincing. The Ladds had a three-week expedition planned for September 2009 to raft the upper section of the Yangtze River—a 200-mile stretch that’s been navigated less than 100 times. Ever. We were in.

But we weren’t raft guides. And we didn’t have big-water rowing experience. Sure, we’d rafted and kayaked before, and we could read basic water. But on the world’s third-longest river? With only five months to train? On the Gallatin, Madison, and Yellowstone? Were we crazy?

May 2009

We set out to begin training. Much to our delight, flood stage on the Yellowstone came early and in full force. While Livingston struggled with roads and residences cut off from the mainland, we took the opportunity to get on the river.

Because we expected the Yangtze descent to be a Class III trip, we figured the Yellowstone would be most similar to what we’d be running—high volume, low gradient, big eddy lines, wide river, lots of debris at flood stage, and dangerous to swim at high levels. We spent days practicing boat positioning, ferrying back and forth, catching eddies, exiting eddies, and avoiding snags and floating debris. All went smoothly, and our confidence on the oars increased. Flood stage wasn’t so bad after all!

June 2009

As springtime ensued, we moved over to the Gallatin. The river was flowing big at around 5,500 cubic feet per second (cfs). Water nearly flushed over House Rock. With it winding so closely to Highway 191, the Gallatin offered an ideal place to perfect scouting lines and water-reading skills. The Mad Mile looked angry, yet lured us in to play.

“If you can cleanly run a river like the Gallatin at higher flows, I believe you can run any river in the world,” Eric urged.

August 2009

The Madison River's Beartrap Canyon is a lovely collection of rocks, drops, and whitewater fun for all. With the expedition only a few weeks away, Eric, who has 24 years of guiding experience, wanted to see how we reacted to some solid Class IV moves. Confident from the summer’s training, we were ready for anything.

As we approached the Kitchen Sink scouting area, we were all slightly surprised—2,500 cfs sure looked a lot bigger than it sounded. Carefully selecting our line through the myriad of holes, it was obvious where we should not go, yet our anticipation heightened as we made our way back to the boats.

Our dreams of running a clean line down the Sink quickly shattered. Punching the first hole jolted the raft, rocking Troy from the oars and sending us into a tailspin. Mike and I tried to help on paddle assist, but it was already too late. We were headed straight toward Camelback—35% of the water was going left, 5% was going over the top, and 60% was going right. We ended up on the 5% “that’ll never happen” line. The water swept the boat sideways, momentarily stalling us on top and giving us just enough time to peer over the ten-foot drop.

Careening over Camelback was a huge wake-up call. The fact that we got to practice swims and rescues may have been a bonus in our training efforts, but the river was chewing us up and spitting us out. Although the raft never flipped, I flew out and took a huge swim. I churned, regurgitated, and flushed through the bottom. Troy also fell out but had time to grab the safety line.

September 6, 2009

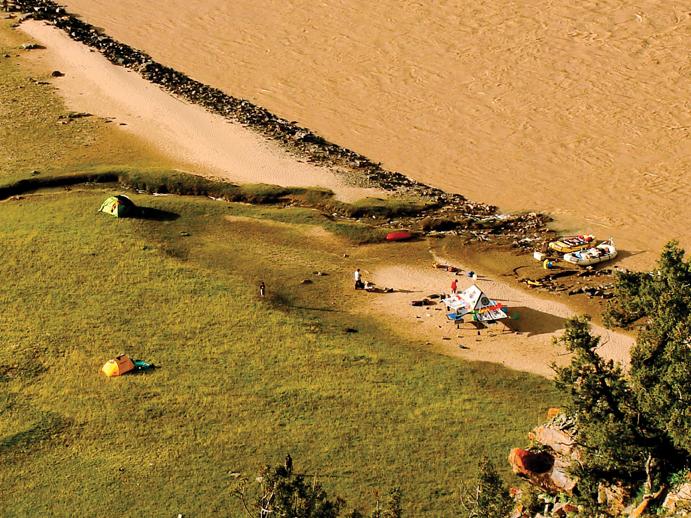

The expedition begins. With three rafts and two safety kayakers, we put in on a tributary to the Yangtze about 1 kilometer upstream. This mere "tributary" was the size of the Yellowstone… at flood stage. It was too late to turn back now.

When we reached the confluence with the Yangtze, we were in awe of the surging water before us. A 50-year monsoon cycle had bombarded the area for the last month, and we were headed straight into the zone. Little did we know our Class III trip was going to turn into a Class IV/V.

September 9, 2009

“Eddy out right!”

The Yangtze’s flow, now exceeding 35,000 cfs, made the ferry across the river excruciating. The small eddy was barely big enough for two boats. Swirling water churned in every direction, thrashing our rafts while 4,000-vertical-foot canyon walls obstructed any view of what lay ahead.

The canyon narrowed from 300 yards wide to 75 yards wide and made a sweeping right turn. As we rounded the corner, a gigantic rock ledge on the left bank had water surging over, through, and around its massive structure. The sea of whitewater in every direction was overwhelming; huge eddy lines and whirlpools were everywhere.

Eric abruptly spun backward, trying to gain more strength at the oars with his backstroke. We did the same. “All back, all back!” everyone yelled.

Lateral waves swept against the rafts, which appeared vertical as we maneuvered through 15- to 20-foot breaking waves. Water surged. With each paddle stroke we dug harder than ever, remembering what Montana's rivers had taught us. Emerging upright and unscathed, cheers of victory rang through the team.

September 12, 2009

We were tantalizingly close to completing our mission. As we scouted a 1-kilometer section of Class IV rapids, two lines were visible through the mass of water. We decided to run two rafts on the left and one on the right, execute, and eddy out. Apprehension mounted as we walked back to the rafts. We had to make our line.

The swiftness of the water was shocking; we had to make our moves faster than expected. On the left, we had to make multiple spin maneuvers and punch three car-sized holes; the line on the right required a big move right to avoid a bus-sized hole, and it was followed by ten-foot waves and a quick left to avoid a ten-foot drop and additional hole.

We pulled it off. Cheers of victory rang from the team. Our expedition still stands as the only successful navigation of the upper section of the Yangtze in the last three years.

May 2010

Watching the chocolate-tinted water of the Yellowstone rising with spring snowmelt, I consider how lucky we were to achieve success on the Yangtze—and how much our local rivers taught us. I realize now that the movement of all rivers is the same: unyielding, unforgiving, and unpredictable. And without the steep, rocky, cold, technical, diverse water we mastered on the rivers of southwest Montana, our story could have been very different. The Gallatin, Madison, and Yellowstone stayed with us as we traveled to the other side of the Earth, through 200 miles of the world’s most powerful waters, unexpected monsoons, and Class IV/V rapids on the mighty Yangtze River.

To learn more about the Yangtze descent, visit yangtzedescent.com.