Uncharted Waters

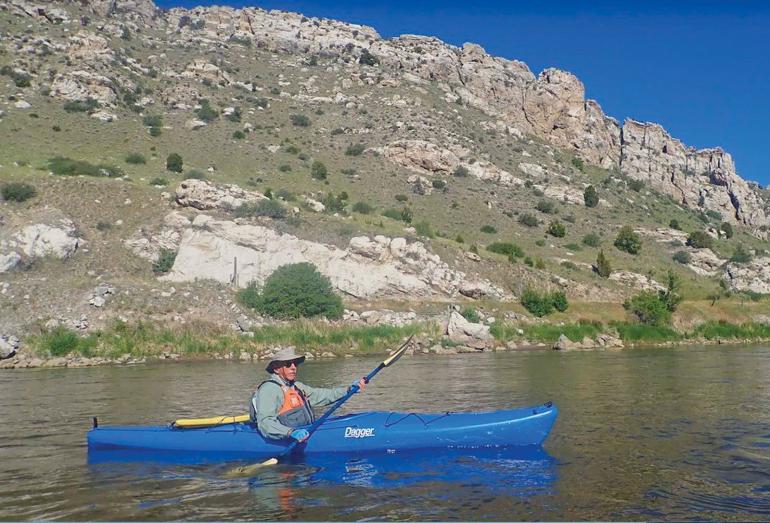

The early days of kayak-touring around southwest Montana, and beyond.

“Would it be possible to paddle a sea kayak on the rivers around here?”

Mike Garcia, the owner of Northern Lights, answered, “Sure. Why not? I’ll order one for you.” This was the early 1980s.

At the time, I’d paddled a canoe a fair amount but had the usual problems. It’s hard to find a partner who’s available, and one who doesn’t worry that canoes have a reputation for being tippy. And I love the look of a kayak. It’s more like a Porsche 911, not the water version of an Oldsmobile 88 that a canoe is. I’d gone whitewater kayaking a few times with a borrowed boat and competent mentor. I’d done it enough to say I’d done it. Although I’d rolled successfully in the combat of whitewater, which is not the same as rolling at the Swim Center, I liked the idea of a kayak for touring.

In addition to several trips down the Smith, through the years we paddled many kayak miles camping on all the local rivers.

I had a friend who owned a Folbot, a fabric-covered sea kayak that could be disassembled and folded up. When our canoe group went out on adventure, that’s the boat he took. Unlike whitewater kayaks, it was designed for touring, and it seemed to be the perfect watercraft. To educate myself, I went to the tobacco and pipe shop on downtown Main Street, which sold magazines on every subject—everything from Soldier of Fortune to Flower-Arranging Quarterly. I found several canoeing magazines that featured hard-sided 17- to 21-plus-foot sea kayaks. Perfect. Mike ordered one for me, and he let me take it for a test drive before I got out my checkbook.

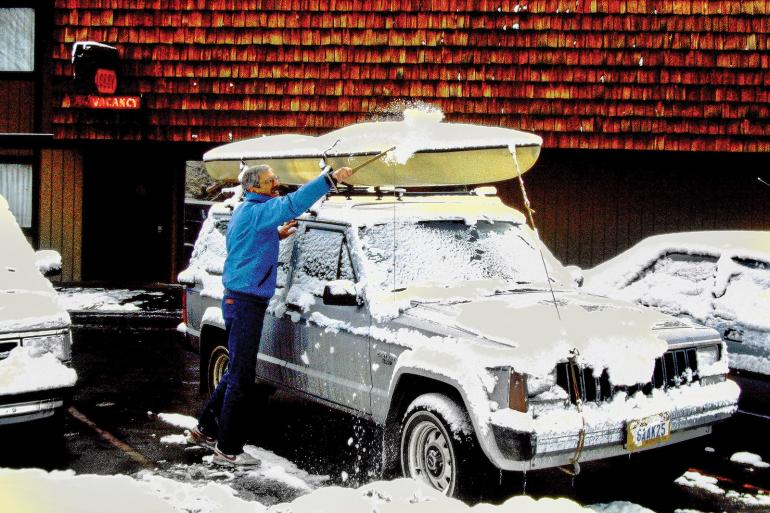

Made of indestructible rotomolded plastic, which boating folks call “Tupperware,” the boat was heavy. I threw the beauty on top of my SUV and headed over to the area that we now know as Bozeman Beach (once a mineral-rich toxic pool, the pond had recently been declared suitable for recreation by humans). I loved the boat from first sight, a sleek red cousin of an Eskimo kayak. It paddled smoothly and I felt comfortable right away. Mike said it’d be hard to tip. It wasn’t that hard for me—I put its stability to the test, leaning this way and that, ever further, and sure enough I splashed and swam. The boat dumped me; I had to buy it.

Each spring my son and I would make multi-day camping trips with our kayaks. The first time was the Smith River, before the time of permits. The river was a little low, and we felt smug as we glided over gravel bars that hung up the big rubber rafts. Those cargo-hauling tubs made us envy their carrying capacity of steak and beer-stocked coolers, but we smiled as we watched the struggling boatmen climb in and out each time they grounded. And smug we were when the temperature dropped and the sleet began, as we were snug in our kayak cocoons, weather unable to reach us under our spray skirts. The river rats in their rafts, meanwhile, looked glum. They couldn’t have been colder or wetter if they’d been clothed in sponge.

As we traveled, we frequently were greeted with, “Hey, lemme see you do an Eskimo roll.” No one on the river had ever seen a touring kayak. They seemed to assume a kayak and whitewater rolling were inseparable. “Can’t do it; we don’t want to spill our coffee,” we lied.

From the road, the section we’d seen that had rocks here and there looked quite different from the cockpit of the kayak. Rocks were bigger, waves much bigger, and gaps were smaller.

In addition to several trips down the Smith, through the years we paddled many kayak miles camping on all the local rivers. At one time or another we paddled segments from Carbella to Billings on the Yellowstone. We camped along the Madison, Jefferson, Snake, and Big Hole. We did several trips through the Missouri Breaks.

The Big Hole had the big plus of dropping to floatable levels early in the season, so we could hop on right when school got out. Using a highway map to plot our travels, we hadn’t scouted the river until we drove along it. We saw the need to portage at the Pump House diversion upstream of the Divide Bridge. We passed some boulder-filled stretches that looked like fun. Buoyed by ignorance and overconfidence, we launched at Sportsman Park and were quickly bobbing along, all smiles. Over the course of the next three days, our smiles of contentment occasionally morphed to adrenaline-pumped smiles as we encountered three challenges to boaters: rocks, mosquitos, and sweepers.

From the road, the section we’d seen that had rocks here and there looked quite different from the cockpit of the kayak. Rocks were bigger, waves much bigger, and gaps were smaller. Once in this rock garden, I remembered a lesson learned long ago in high-school English class from Macbeth: sometimes you just can’t turn back from a bad decision. As it happened, we zigged and zagged and made the run smoothly, feeling exhilaration, not regret, at the end.

We camped at Divide and discovered our lovely campsite had an Alaska-worthy infestation with June mosquitos. When we entered the tent, a mosquito horde flowed through the door, like being sucked in with a vacuum. Intolerable. We grabbed our dinner fixings, fumigated the tent with insect spray, and zipped it shut. We searched for a spot with fewer bugs and ended up dining on concrete, sitting in the center of the Divide Bridge. A little breeze and no foliage meant for minimal mosquitos. Ah, wilderness!

We discovered that few folks fished and floated downstream of Glen. We didn’t know why. We found out. There were stretches of river that braided and braided again, and ascertaining the correct channel was impossible for those, like us, unfamiliar with the route. Sure enough, as we entered a small side channel, we encountered a hazard to navigation. A large tree, fortunately free of many branches, had fallen at a right angle from the right bank and extended about two-thirds of the way to the other bank. Sure enough, about ten yards downstream a mirror image confronted us: a second tree river-left jutted two-thirds across the river. We had time to stop and scout. Our assessment was that in the slow current, one could get around the first log, pivot and do a strong back ferry, which would allow passage around the end of tree number two. Our assessment was incorrect. Joe went first and almost made it, getting flipped and dunked by the tip of the second tree. As soon as he righted and it was apparent that he was okay, I laughed, of course. Like laughing at someone who slips on the ice until you step on the same spot, I figured I could learn from his rookie mistake and apply more effort into my back ferry to make the run successfully. Joe got the laugh that time.

As we got the boats ashore to dump them, we had one of those unexpected special moments that we all go into the wilderness hoping for. Stepping through tall grass, I was about to put my foot down. Whoa, the landing for my foot was a white-spotted clump of red-brown fur. A fawn. What a precious moment. We backtracked and left the little fella alone; he stayed put, not a muscle moved.

As I think about that trip and many others, I marvel at the evolution of the modern recreational kayak. For years, there were only a few options. Whitewater kayaks, short and slippery, required technique for everything from entry to paddling. Once inside, you were essentially wearing the boat. The second option was the sea kayak, long with narrow beam, designed for cruising lakes and oceans. A V-hull is suitable for tracking, but for maneuvering on a river, not so much. I owned a third option, a down-river racing kayak. Lightweight, snug cockpit, longish, and not great for the zig and the zag. Fast, not comfy.

Along come today’s recreational kayaks: 10 to 14 feet long with hull designs that emphasize stability and maneuverability. The cockpits are roomy, even very roomy, and are fitted with seats that are actually comfortable. And we’ve all seen grandmas and five-year-olds scooting along like water spiders. Very forgiving. Clunky wood and metal paddles have been supplanted by affordable lightweight composite ones. The only downside to these new boats is their popularity. River access points can look like a YouTube video of rush hour at an intersection in Pakistan.

The forgiveness of these boats invites carelessness. Wear your life vest. Don’t trail a rope. Respect moving water; you can get pinned against a rock or other obstruction on an “easy” stretch of river. Hit something? Gonna tip? Three rules to prevent capsize: lean downstream, lean downstream, lean downstream. Did you tip? You violated one of the three rules.

Wear sunscreen. Have fun. Bon voyage.