The Great Grizzly of the Sky

Ah, spring! The season when Tennyson said a young man’s fancy “lightly turns to thoughts of love.” But for the region’s grizzly bears, newly roused from their winter’s fast, love can wait. It’s all about getting a good meal.

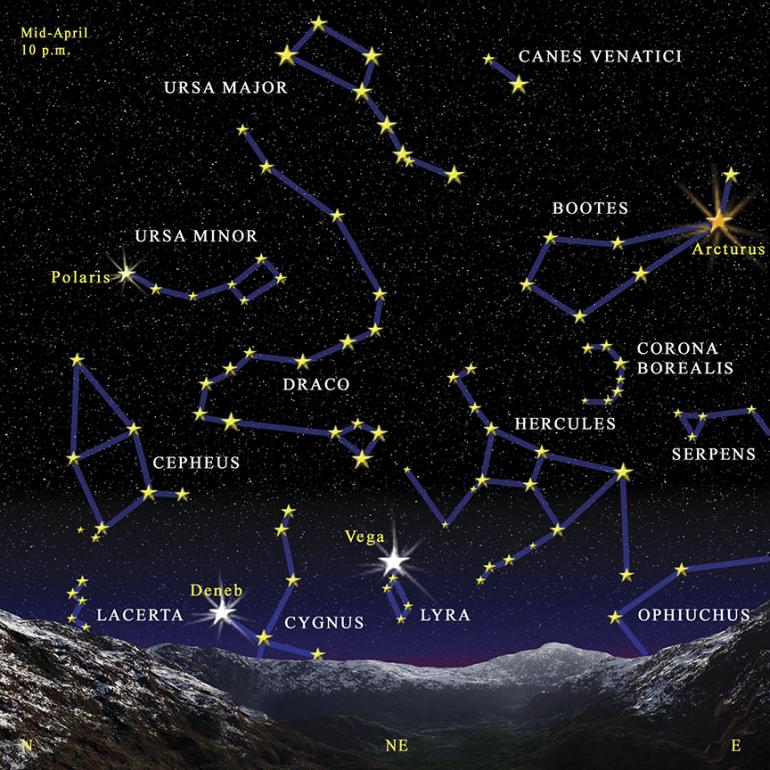

It seems fitting then, with bears once again abroad in the wilderness, that the Great Grizzly of the sky—in the guise of the Big Dipper—should also be roaming at its highest on the warming eves of spring. This is the time when the Dipper can be found arching just north of overhead in the middle evening, the four stars of the bowl and the three of the handle unmistakable in the heavens. The bowl forms the bear’s back, the handle its tail. Fainter strings of stars issuing from the bowl’s bottom form the legs, and a faint triangle of stars ahead of the bowl makes a head for the bear. Altogether these stars form Ursa Major, the Great Bear.

It doesn’t take much study of the bear’s gross anatomy to note something odd about its nether regions, and there are plenty of tall tales to explain the bear’s long tail. The classic Greek tale relates that the Great Bear was once a great-looking maid named Callisto, an attendant of Artemis, goddess of the hunt. Callisto was sufficiently attractive; in fact, she attracted the attention of Zeus, king of the gods, who rather forcibly seduced her one day in the woods. It wasn’t long before Zeus’ dalliance became noticeable in her figure and produced a son named Arcas. As a result, she was banished from the virgin Artemis’ presence, and Zeus’ wife, Hera, was none too pleased either. Hera exacted her revenge upon the hapless Callisto (which was easier than exacting it upon her husband) by turning her into a bear.

And so Callisto wandered, until one day years later when she came upon Arcas in the woods, all grown up and a fine hunter besides. She lumbered toward him, but all Arcas saw was a future bearskin rug for his hut. As he drew back his bow, Zeus intervened; he turned Arcas into a bear as well, and tossed them both into the sky by their tails where we see them today—Callisto as Ursa Major, and Arcas as Ursa Minor (the small bear) or the Little Dipper, with the North Star (Polaris) marking the tip of his tail. Of course, that was quite a windup and throw even for a god, and in the process, the bears’ tails stretched.

The Mikmak Indians from the East also find a bear in the Big Dipper, but only in the bowl. The handle stars designate three hunters chasing the bear, and the brighter stars of nearby Bootes (the Greek herdsman), including bright Arcturus, make an arc of four more. The hunters—all of them birds of various sorts—start the chase in the spring and continue as the seasons change. In the autumn, when the pattern is seen dipping close to the Earth in the north in the early evening, they shoot and kill the bear, its blood staining the trees in their lurid colors.

Thereafter, through winter, only the bear’s skeleton remains, rising high into the sky. By the next spring, a new bear, rousing from its winter’s sleep, emerges from its sky den (the circular pattern of nearby Corona Borealis—the Greek Crown) to take its place in the bowl pattern. And the hunt begins again, matching the cycling seasons and the circle of life, death, and rebirth in the crucible of spring.

It’s a story for the ages. Just look northeast on the warming nights of spring, in the midevening, and you’ll see them all: the den of Corona Borealis, the kite-shaped Bootes with its hunter stars, the Little Dipper anchoring the North, and the high-arching stars of the Big Dipper, signaling the eternal cycles of Earth and sky. Ah, spring!