Big Bird in the Sky

Swan on the wing.

Of all the fowl that soar the skies or glide the waters of the Rocky Mountain West, none is larger—or more elegant—than the trumpeter swan, the biggest native North American bird there is. You can see them on the rivers of Yellowstone National Park or other venues about the region. But failing that, you can always look to the sky, where a copy of this “Big Bird” sails across the summer night in the midst of another river: the Milky Way.

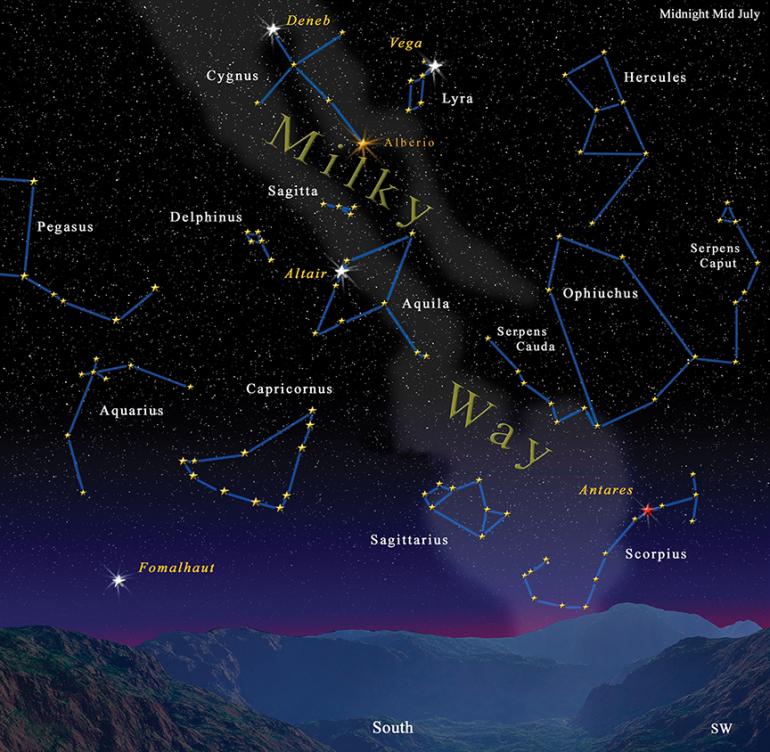

To find the swan, look first for the Summer Triangle of bright stars made up of Vega, Altair, and Deneb, dominating the eastern sky by the late evening (around 11pm local time) in mid-June. Deneb, the faintest and easternmost of the three, marks the very top of a cross-shape of stars that lies in the glowing river of stars that forms the edge-on view of our galaxy. This shape in fact marks the Northern Cross, an alternate name for Cygnus the swan. Deneb marks the swan’s tail, and Albireo—the star at the bottom of the cross (and a lovely gold and blue double star in telescopes)—marks the head at the end of a long neck; the crossbar outlines the outstretched wings. Wait a few hours and the swan will fly right over your head with the turning of the earth (and thus the sky); by mid-August, Cygnus is already overhead by 11pm.

There are big stories about this big bird. The Greeks sometimes said this was Zeus in the guise he took when he snuck into the boudoir of Leda, Queen of Sparta. The dalliance produced a pair of eggs: from one emerged the Gemini brothers, Castor and Pollux, and from the other, Helen of Troy and her “femme fatale” sister, Clytemnestra. These four players set off some of the biggest soap operas in Greek mythology, including the Trojan War.

Another tale says that Cygnus was originally the buddy of Phaethon, the son of Helios who drove the sun chariot across the sky each day. On one particular day, Phaethon convinced Daddy to let him take the chariot out for a cruise himself—with incendiary results. Unable to control the horses pulling the chariot, Phaethon lurched out of control and threatened to immolate the entire Earth. Zeus ended the joyride with a well-aimed thunderbolt, and poor Phaethon fell to Earth and into the river Eridanus.

The grieving Cygnus took it upon himself to retrieve the remains of the late Phaethon from the river, and he so reminded the gods of a diving swan that Zeus turned him into one. He flew up into the heavens and remains there today against the glow of the Milky Way—the trail of burning cinders Phaethon left behind in his ill-fated rush across the sky. Wakinu himself is seen in the cross-shape that also makes Cygnus.

The Shoshone of Idaho also link Cygnus to the Milky Way, but as a great gray grizzly bear named Wakinu. Wakinu was banished for trying to steal a brother bear’s meal, and he wandered into the snow country. There he spied a trail in the sky, hopped up and shook the snow from his coat as he journeyed along it. Wakinu had found the Bridge of Souls, and the sparkling snow shaken from his coat now illuminates it as the trail we call the Milky Way.

Big Bird or Big Bear, Cygnus sails the night sky every summer, and more than human eyes have been watching it. For four years ending in 2013, NASA’s Kepler spacecraft stared at one of Cygnus’s wing tips, observing 100,000 stars in the space between Deneb and Vega, watching for tiny, periodic stellar brightness drops that betray the presence of planets transiting across the faces of their parent stars.

Planets are still being identified in its treasure trove of data, including smaller and smaller ones. The swan is revealing at last the near Earth-sized planets astronomers are hunting for among the stars, and that is big news to trumpet indeed!

Jim Manning, formerly the executive director of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific in San Francisco, lived outside Bozeman for many years and visits regularly.