Bearable Bear Canyon

The history of an early downhill-ski area.

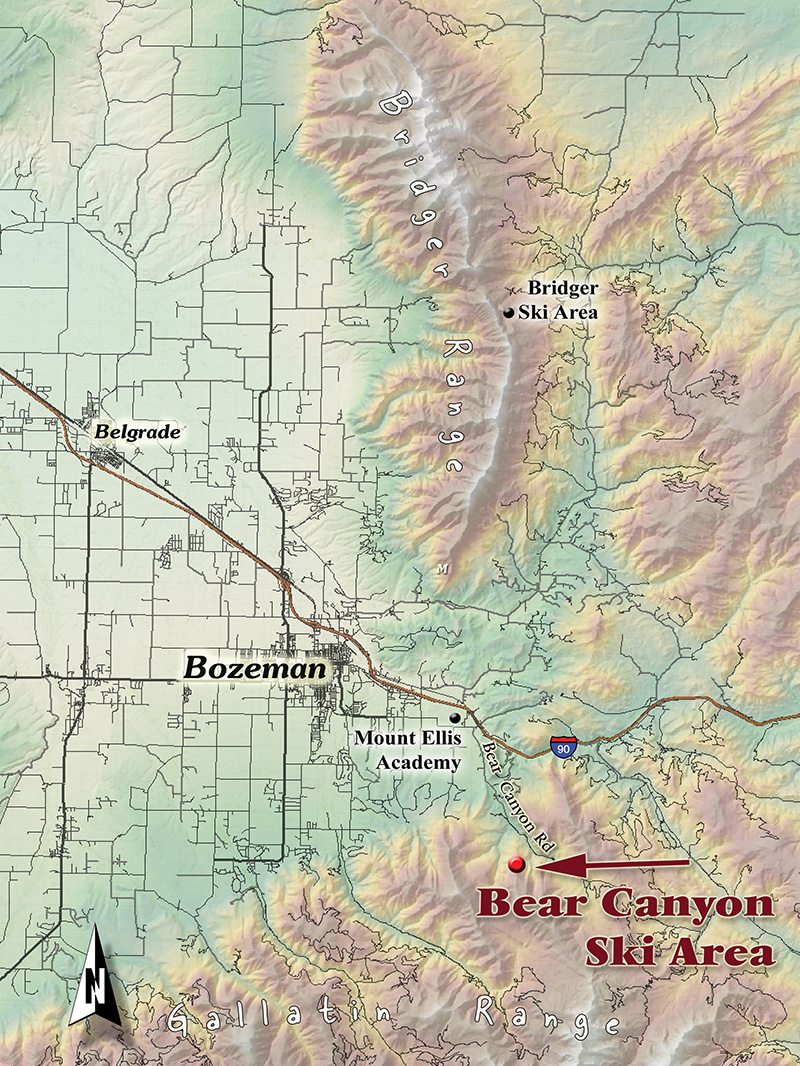

Bear Canyon is one of Bozeman’s greatest treasures. Home to one of the area’s first ski hills, Bear Canyon is now one of the most convenient recreation sites around Bozeman. A mere eight miles from downtown, Bear Canyon offers large tracts of state and Forest Service land, miles of hiking trails, and a thriving wildlife population. Bear Canyon Road travels along an old flume path and runs into state land just three and a half miles up. Within those three and a half miles are just over 60 residences on privately owned plots and state-leased land.

In the late 1800s Bear Canyon was booming. The Cooper Saw Mill was located up Bear Canyon Road near Bear Lake in a town called Commissary. Gwen Rankin, a previous resident of Bear Canyon, wrote of the saw mill, “Senator Clark, who played a big role in the political and financial development of the state, had built a reservoir and log flume to carry logs on contract for ties down to the railroad. He put a man named Cooper in charge... 600 people lived up there in a small company town with its own church and school.”

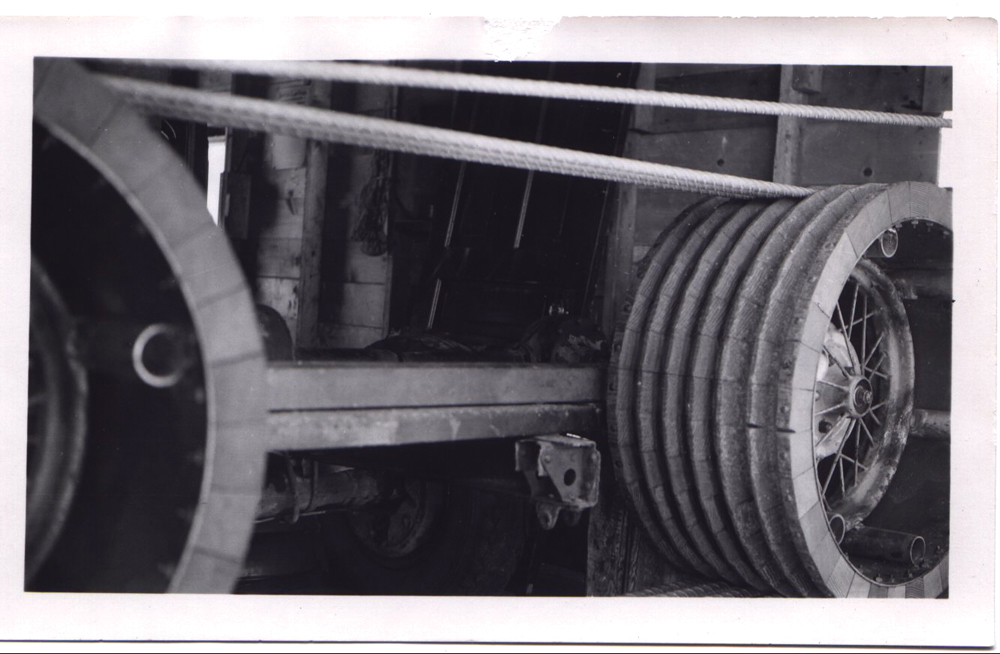

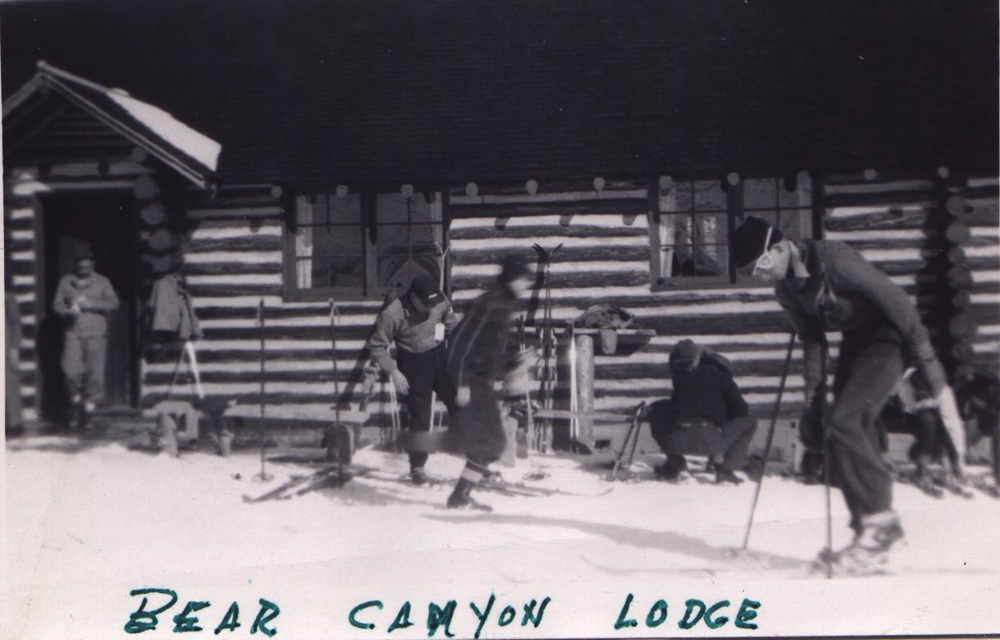

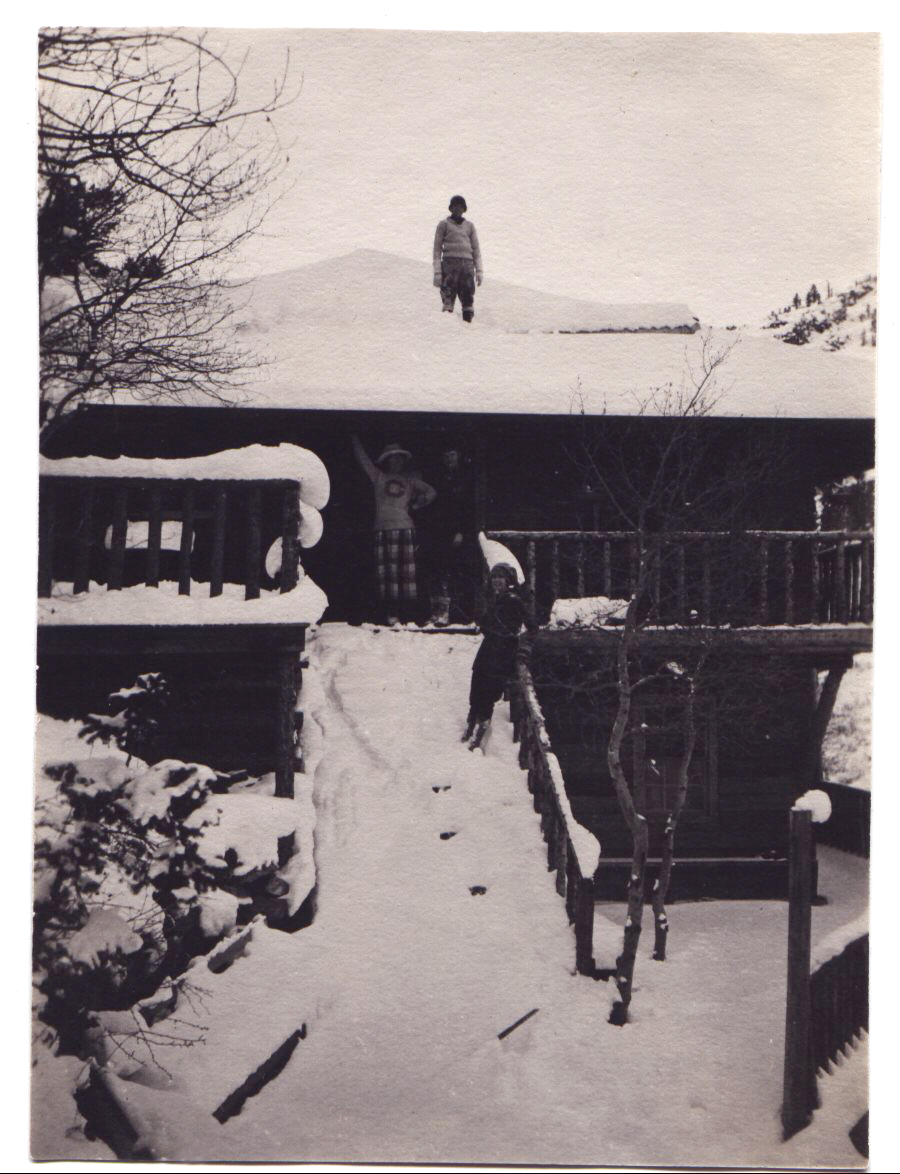

In 1897, Bessie Alice Williams’ family homesteaded the area with a one-room cabin. In 1899 Bessie married Orlando Lawrence and they later built another cabin about a mile and a half up the road. Years later, Bessie and her son built an updated cabin in which Bessie would spend the remaining years of her life. (That cabin is now owned and operated by Mary Sadowski and Tom Skeele as the Bear Canyon Guest Cabin.) While the Cooper Saw Mill kept folks busy logging and producing railroad ties, many young men were off to World War II. For those back at home, Gallatin County was introducing one of its first ski areas. A downhill run was developed, and using an old car motor donated by Adolph Peterson, local skiers built a rope tow. Next, using funds from the Works Progress Administration, they constructed a warming cabin.

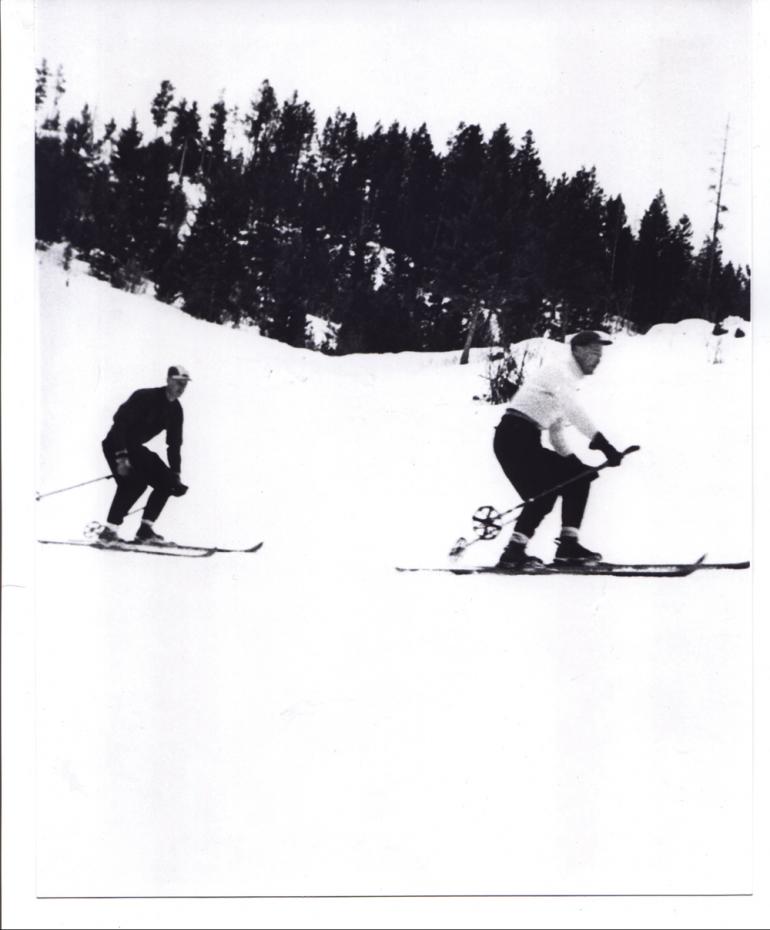

In 1941, a time when scarlet fever took lives across the nation and Hitler and the Nazis dominated the headlines, Bozemanite Kay Widmer was writing a weekly column for the Chronicle entitled “Dope on the Slope.” The column told the tales of skiing at Bear Canyon. Widmer wrote of Shep, the skiers’ mascot famous for running in circles and demanding that anyone throw him a stick. She wrote of hard-luck skiers, trail conditions, the “weather dope,” best- and worst-dressed skiers, and events at the ski hill. It’s hard to believe that over 50 years ago, skiers in Gallatin County had something we lack today, but they did—public night skiing. For a short time, railroad flares were used to light up sections of the run. Albeit exciting, this was exceptionally dangerous as skiers raced beyond flares and into pitch-black darkness.

Don Langohr, whose family owned Langohr’s Flowerland from 1898 until 1979, remembers Bear Canyon fondly. “Fifty years ago it was just a spot on the mountain,” says Langohr. “I skied Bear Canyon in the 30s and ‘40s. There was a rope tow, a log cabin, and a ski jump by where the old parking lot was... it was the only skiing around here and a big step up compared to skiing before that.” The new amenities included the log cabin “lodge,” complete with food and beverages. No more than a place to warm your feet by the fire while enjoying a cup of homemade chicken noodle soup, Bear Canyon’s log cabin was a luxury for the day.

Not only were the “ski resorts” different back then, the skis themselves were a far cry from the technology used today. “Back then, skis just had toe straps,” says Langohr. “Around the war they came out with traditional ski bindings, but not safety bindings like today. Back then we called them bear traps—if your leg was in there and you went down, your leg would break. During the war the 10th Mountain Division had some real nice skis with good bindings and strong metal edges. After the war was over everyone had a pair because they were war surplus. What we ski on now bears no comparison to what we used then.”

Bear Canyon’s glory days lasted until things got underway at what is now Bridger Bowl. When Mount Ellis Academy (a private Christian school for kindergarten through 12th grade) took over the ski area, the rope tow was replaced with a one-person chairlift. A ski lodge was built and the area was open to the public. “We used to have 100-150 people out there every Sunday,” says Darren Wilkins, the principal of Mount Ellis.

The lift ran until 1975 when some cracks were discovered in the lift poles. The lift was shut down and no one used the ski area for some thirteen years. In 1988 Mount Ellis Academy put in a T-bar, cleared all the runs, and installed lighting on the main run. The school has been using the ski area for its students ever since.

In 1962, Margaret (Jones) Lovely began submitting a weekly column to the Chronicle entitled “Bear Canyon News.” Frustrated with the “tee-totaling” society columns of the day, Margaret had intentions of another nature. She wrote of daily life in Bear Canyon, of wildlife encounters, and hunters emerging from the backcountry with success in tow. She wrote of Jeeps flipping on heavily packed snow, and the birth of spring and mosaic of beauty that followed.

Another aspiring writer used her talents to depict Bear Canyon. In late 1972, Gwen Rankin ran the following ad in Harper’s Bazaar: “Share Our Wilderness Cabin Life—receive a long personal letter and photo every week. Send 50 cents for the first letter and $12 for six months.” Folks replied to Rankin’s ad and soon she was weaving tales of life in Bear Canyon.

Rankin found that time and progress moved slowly in the Canyon. She interviewed Bessie Lawrence (Grandma Lawrence as she was known to the neighborhood by then) on many occasions. Lawrence recounted a day when the sheriff came by to tell her it wasn’t safe for a woman to be living up in Bear Canyon all alone. “I showed him my gun ‘n he said can you shoot it, ‘n I told him I never missed my bear."

Rankin lamented to Lawrence one winter about running short of exciting news to write about. Lawrence replied, “They might as well know there’s not much happenin’ up here in the winter. Tell ‘em we jest hole up like the animals—jest stay inside and keep warm now that everybody except you got a television.” Even Rankin began to feel the slow tick of technology in the Canyon. “There just aren’t enough hours in the day to get everything done that should be finished before the big snow comes,” she wrote. “We get up an hour before sunrise and do some jobs by lantern-light at night.”

Today, residents of Bear Canyon face different challenges. Of particular note is increased traffic on Bear Canyon Road, a winding, narrow road with a number of blind turns. As one resident puts it, “There are two kinds of people in Bear Canyon: those that have been in the ditch, and those that haven’t.”

In one of Rankin’s letters, she wrote, “That brings on another local controversy, do elk shy away from logging roads.” One has to wonder what she would think of the elk’s reaction to motorized vehicles in Bear Canyon today.

Residents of Bear Canyon use Park Electric Cooperative electricity and pay significantly higher rates coupled with occasional power outages. Wildlife still inhabits the area but terms for dealing with the animals are different today. Rather than wielding your shotgun to fend off curious or angry bears, the Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks is now called in to relocate the troublesome bruins.

Old abandoned fencing has taken the lives of a few animals and is of great concern to some residents. Furthermore, those in Bear Canyon worry about their water quality today due to extreme sedimentation in Bear Creek. A majority of residents are opposed to the Gallatin National Forest Travel Plan and its proposed Bear Canyon uses.

Bear Canyon has long been adored for its wild beauty. Just a stone’s throw from the city life of Bozeman, it is readily accessible and heavily used. Though the town of Commissary, the Cooper Saw Mill, and the old rope-tow are gone, Bear Canyon is not. Tread lightly and with each step, listen to the Canyon tell its tales of a time long ago, when the living was slow and the life was wild.