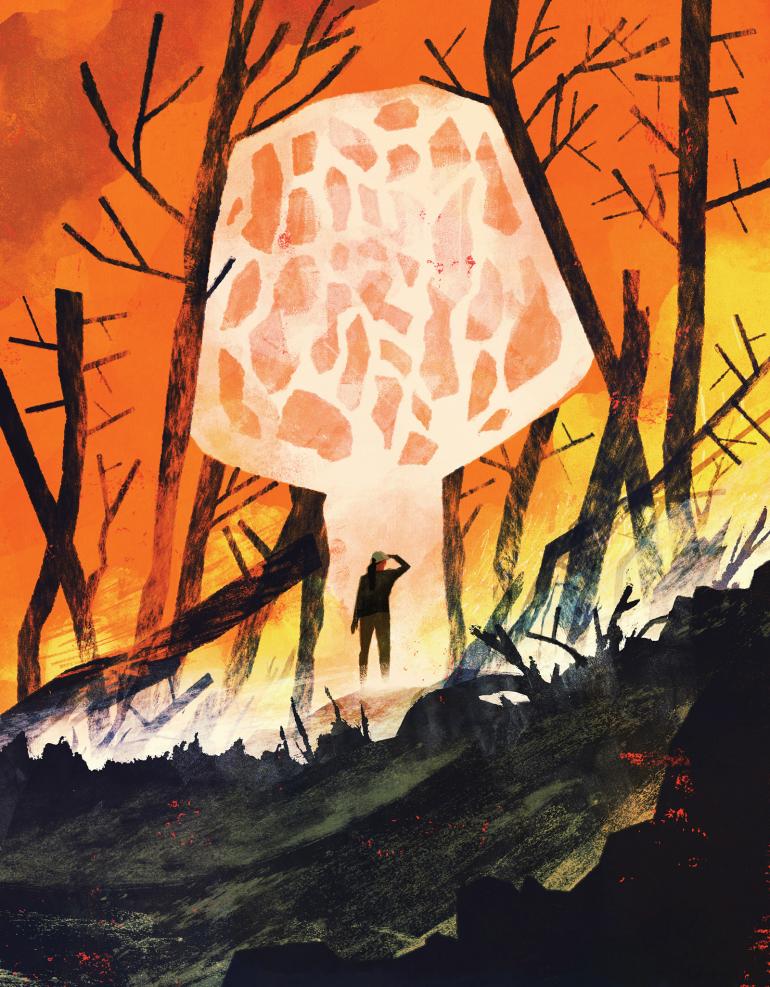

Life After Fire

Exploring a repainted landscape.

We’re driving into our fishing hole after the fire, to see if it burned. I suck dust through my open window, past sage and rabbitbrush and juniper that browns to rust in winter, more trees than you’d think for hills this dry. Granite boulders knuckle up from the sage and in the lodgepoles up the ridge, scorched now. You can see the full ridge from the basin behind it. Head-on, the ridge looks like a mountain that never burned.

The road was the fire line. Crews with picks and hoes scraped sage to soil, lopped juniper branches up from the ground, before anyone knew which way the fire would run. This fire didn’t run far. Fanned by wind that always shoots up this valley, the fire cooked slopes choked with deadfall and underbrush without incinerating earth. More violent fires tilt up from the ground to launch logs across ravines or blast gusts into crowns. This fire smoldered and crept until winter doused it.

Fire hits closer to home every season as dry years pile up against drought. It blazes through stands I can see from town; it torches ridges and gullies to the north, starting high and back from roads where it consumes entire horizons. This is rugged, rain-shadow country, cactus and granite, rattlesnakes in the bunchgrass, big cats behind boulders, steep slopes of downed trunks waiting for fire, for rain, for return to what they were before they were trees. Winds gather across western ranges, stumbling over bottomlands and driving up the headwaters of these mountains, rolling clouds that wring themselves dry then fleece over the divide to hurl lightning where I live, no rain. When a flash sparks a snag, I watch smoke trail across the valley from ridges I have hiked and the gullies that cut them, so brushy and craggy when I’m in them I can only guess how water falls. But water falls here, over ground where I’ve walked and where I haven’t, guiding trickles of midges and moss toward mainstem waters from folds of land where all life meets, my life and the midges and the sage and the trout in our fishing hole, which we fished with my father-in-law when he could still fish, before the fire, so it’s more than just a fishing hole. I have tethered my life to this map that lives in my mind.

The canyon cinches and drops over boulders, no banks. Water slides into the gullet where I can’t follow.

Big fires torch tens of thousands of acres. They raze homes, destroy lives, or claim them. They cost millions of dollars to contain or suppress. They silt the air, they clog watersheds, they drive the living world to force life out of altered ranges. They denude home ground. Burned ground is a body without its skin, and a skinned body is raw like birth or death, especially if it’s still alive. The burn that remains after fire can shake us. We want our world to be unshakeable and we don’t know what to make of a moonscape, of familiar forest scorched to skeleton in the blink of a season, of land that ghosted to dust while we watched. I want to know what remains at our fishing hole.

We drop into the basin behind the ridge. My husband is driving, our daughter strapped into her car seat. The basin did not burn. Above sage flats, rock shrugs off rain that rarely falls on slopes sloughing granite crud that will never become soil. Mineral chips of quartz and feldspar cartwheel down cracks so the only way trees grow is to ram roots deep where water gathers. The burn is higher up, the ridge parched and drawn around the bones of what it was and still is.

I want to look for morels there.

I’ve hunted morels in wetter country across the divide, where fire lifted and pitched trunks in corkscrew winds through wilderness whose mountains drink more rain. Two years after fire, the earth was shocked with blossom, beargrass beaming pollen like torches of light. Blackened fir trunks without needles, air so clear water rose and flashed like crystal. Bog orchids with petals like wings, pink lousewort drinking color from sunlight. As if everything drinks this way after fire. Up high, the land heaved into light, slopes steely with deadwood numbing to white, miles and miles of creek peeling back to a horizon savaged by fire and weighted more fiercely by its nakedness. I stood in talus, in a hollow of sky above tides of rock hoarding runoff in boggy wrinkles, in crevices of duff and ash flaked with bedrock and bored by root hairs, spun fungal and webby as membrane.

Closer to home, plants are wooly and they hug the ground close to hold water before a fire or after it. We follow the road through the basin along the feathered edge of the burn, dropping to cross the creek in the hollow where we like to pitch a tent on a bend offered up like the flat of a hand.

Our fishing hole glints with light. We catch brown trout in July, small as my palm, with our daughter, one after the other. We’re tucked into a fold behind the burn where water pools as it drops, the light spun so securely I almost believe the trees here might never burn. It’s wetter away from the road, dim and cool. We walk the creek, flattening horsetails as we funnel beneath boulders seized by moss. There’s lichen that looks so brittle it will crumble if I touch it, so fleshy it will forever bear the blot of my finger, but then I touch it, and it holds firm.

I stand in talus, in a hollow of sky above tides of rock hoarding runoff in boggy wrinkles, in crevices of duff and ash flaked with bedrock and bored by root hairs, spun fungal and webby as membrane.

The canyon cinches and drops over boulders, no banks. Water slides into the gullet where I can’t follow. My husband casts while I watch the current sculpt lines it will never repeat. When I look up our daughter is gripping a small brown, dancing and squealing, knuckles glossed with creek water. I’m worried she’ll crush the fish or drop it so I call to my husband to set it in the water, release it, and he does, but not before I see that she’s cradling the fish in her hands, she knows it’s precious, and it is.

This place will live as long as I do.

Or until September, when, just north of this spot, lightning sparks a new blaze. By October the flames have fizzled, the wild rose is smoldering. Early the next June, I hunt the slopes for morels, our fishing hole secure in a crease between burns in my mind. The ridges are eternally dry. The wind bellows over cliffs, wicks vapor from rock, boulders risen like blisters after fire. But the boulders were here before fire. Maybe fire was here before anything. I tiptoe at first, like the earth will flash to dust if I walk on it. I’m in a bowl I’ve never been in and can’t see far. I scale sheer slopes with ash in my shoes, ash greased with sweat up my shins. No morels. But I find something better: death camas, budding out of its papery sheath. Then chocolate lilies. Deep in a ravine, Calypso orchids squatting for water. High in the burn, fleets of bark beetles sift up on ashy sunbeams, and a bolt of blue like an arrow is a bluebird far from the sage flats that shocks a hole, not through my heart, but higher, nearer my throat, so my breath snags on a pain narrowed so tight it becomes delight, and with every fiber in me, without meaning to, I sing out, but my voice never pierces the slow, sticky parting of my lips.

This summer, again, fire, the third in three years and the largest here yet, another lightning strike high in the rain-shadow. It burns hotter, and longer, down a tributary I have yet to explore. Morels don’t always appear after fire, or I don’t always find them. But I keep hunting. They net fragments of earth as they thumb up from underground knowing things that I never will. At home on the edge of my tub, after hunting the burn, I scrub but ash binds to my skin. I don’t want to come clean, not completely. I want to know where fire burns. I want to know how water falls. I want to know where the morels are.