At a Crossroads

How irrational policy prevents access to millions of acres of public land.

In October of 2021, four hunters from Missouri set out to hunt elk on public land in Carbon County, Wyoming. They planned to hunt within a “checkerboard” pattern of public and private land, typical of many areas scattered around the West. The adjacent private land was part of a sprawling 23,000-acre ranch owned by Fred Eshelman, a wealthy businessman from North Carolina.

The hunters planned to reach their spot by stepping across the corner from one piece of public land to another at the intersection of two fencelines. And, thanks to the advent of GPS technology that allows outdoor recreationists to identify property lines precisely, these four knew exactly where they were. They carried a stile (a short stepladder), which they placed across the fence corner, with one set of legs in the public section they had entered by, and the second set in the section they planned to hunt. They then climbed the ladder across the fence corner, allowing neither their feet nor the ladder to touch private ground. Think of such “corner crossing” as moving a bishop on a chessboard.

No jurisdiction has unequivocally ruled corner crossing either legal or illegal.

The hunters later stated that they had consulted the Wyoming Game & Fish Department website and determined that accessing public land in this manner did not violate any hunting statute—but, as we’ll see, the exact wording of this legal opinion is ambiguous. The ranch manager observed the hunters on the “landlocked” public section, began following and harassing them, and summoned law enforcement.

A game warden and two sheriff’s deputies were the first to arrive. After assessing the situation, the warden told both the hunters and the ranch manager that no game laws had been broken. The following day another sheriff’s deputy was summoned, and he reached the same conclusion.

Then a third officer arrived, told everyone he had direct orders to charge the hunters, and issued a citation for criminal trespass without accusing them of violating any hunting laws. The vexing question of whether any trespass had occurred then went before the court.

History and Geometry

In the analysis of any complex question, there’s no better place to start than with its history. Let’s go back to 1862 and blame the federal government for the mess it created.

As the West began to open during the 19th century, thanks to expansionist instincts and notions of manifest destiny, several entrepreneurs lobbied for railroads and telegraph lines to connect the East Coast with the Pacific. At the time, the federal government managed almost all the land along the proposed routes. Despite the distractions of the Civil War, industry lobbyists and congressional expansionists introduced the idea of granting adjoining public land to the Union Pacific railroad as an incentive to invest, and as compensation for the cost of laying track. The result was the 1862 Pacific Railway Act. After extensive lobbying, the railroad wound up receiving up to 20 sections of land—with one section equal to 640 acres—per mile of track laid across federal property. The result was 40 million acres gifted to private interests.

To avoid creating large, continuous parcels of private land and to encourage homesteaders to settle near the railroad, the charter specified that alternate sections remain public. When the surveying was finished, much of the land adjacent to the Northern Pacific route looked like a checkerboard, consisting of sections of public and private land owned by the railroad. Legislation required the railroad companies to sell some of this land at reduced prices to homesteaders once the railroad was complete. Homesteaders did get some of it, but to raise more capital, the railroad sold off its land-grant property to corporate interests ranging from timber companies (Weyerhaeuser) to mining (Anaconda Copper). Much of this property was then resold to private ranching interests (see my article Our Checkered Past).

The purchasing of a relatively small amount of strategically-located land can monopolize access to whatever public land lies behind it, creating a trophy ranch or a private hunting reserve out of land that belongs to all of us.

Now for some geometry. Whenever two lines meet, they form a point. And if they meet at right angles, that point becomes a corner. You can’t see a point, nor can you pick it up and put it in your pack, because it’s infinitely small. A corner is a theoretical concept rather than an object. Because of that checkerboard pattern, when two sections of public land meet, it is almost always at a point defining a common corner. Is it possible to trespass upon something that doesn’t physically exist? A lot of court time has already been devoted to answering this question, and a lot more lies ahead.

The Scope of the Problem

While the recent Wyoming case has served to attach real names and faces to the issue, the scope of the problem extends far beyond any specific circumstance. Impending decisions about the legality—or illegality—of crossing from one piece of public land to another at a corner intersection have the potential to affect everyone who values the freedom to enjoy the outdoors, on public land, that belongs to all of us.

Currently, some 15 million acres of public land in the West lack any legal access because they are surrounded by private land across which no easements have been established. Think of them as landlocked. In this context, “access” does not refer to roads or other physical means of getting to the property. It means getting from one place, where you have a right to be, to another, all without going to jail.

However, if corner crossing were unequivocally declared legal, digital mapping shows that eight million of those landlocked acres would become accessible by the public. This is a big deal, the significance of which can’t just be measured in acres. As in the Wyoming case, hunters have stood at the head of the line in confronting access issues across the West, but the outcome of these challenges effects a far broader demographic. Hikers, cross-country skiers, mountain bikers, anglers, outdoor photographers, bird watchers… take your pick. All deserve access to the vast tracts of public land currently off-limits due to the absence of a just corner-crossing policy.

Is it possible to trespass upon something that doesn’t physically exist? A lot of court time has already been devoted to answering this question, and a lot more lies ahead.

The Law

It would be easy to summarize the current legal status of corner crossing in one word: ambiguous.

Two important points do seem clear, however. First, the permissibility of corner crossing is determined by individual states, with little consistency among them. Second, no jurisdiction has unequivocally ruled corner crossing either legal or illegal.

The Wyoming case serves as a prime example of the confusion. As noted, the involved hunters did make a reasonable effort to determine the legality of their plans. However, in the previously-expressed opinion of former Wyoming Attorney General Patrick Crank, “Corner crossing from one parcel of public land to another in order to hunt on that other parcel, depending on the factual situation involved, may not be violative (of Game & Fish trespass statutes). Because, to be convicted, the state requires a person to hunt on private property without permission. ‘Corner crossing’, however, may be a criminal trespass.”

Are we clear now? One hopes so, since Wyoming still uses this opinion as policy for public-land hunters and so states in its regulations. It appears that in Wyoming, corner crossing is legal in the eyes of the Game & Fish Department but illegal according to others. No wonder the Missouri Four got their wires crossed.

Anyone crossing at a corner without touching private land on either side only violates property lines in one medium: air. This leads to a question that may sound absurd but holds significant implications as debate over corner crossing moves through the court system. Who owns the airspace?

Private landowners involved in access disputes have already advanced the dubious theory that they do. In their 2013 (losing) appeal of the notorious Ruby River access case, the attorney representing private landowner James Cox Kennedy asserted that his client owned not only the water but the “land beneath it and the air above it.” And commenting on the current Wyoming case, a representative of the Wyoming Stockgrowers Association asserted, “Because of the airspace, whether your foot touches the ground or doesn’t touch the ground, just the act of your body passing through that space would, under that theory that we’ve always maintained in Wyoming, constitute a trespass.”

This reasoning just doesn’t pass my sniff test. How high above ground level do these alleged rights extend? To the height of your lawyer’s chin? To the ionosphere? Does United Airlines need permission from 10,000 landowners to fly from Bozeman to Denver?

As a pilot, I’ve always regarded our FAA as the final legal authority in airspace. Their regulations state that it is generally a violation to operate an aircraft below 500 feet except for take-offs and landings. However, there is an important exception. This restriction does not apply in airspace above “sparsely populated areas.” I have trouble thinking of a corner I want to cross that doesn’t occupy a sparsely populated area. Sorry, guys, but the airspace above those corners seems to belong to all of us.

A Study in Greed

Before we watch the court case unfold, we should perhaps ask why landowners are pushing back so hard against a practice that doesn’t seem to be bothering them in the least, and can’t possibly interfere with agricultural operations.

Welcome to the New West.

It’s been a long time since buying large tracts of prairie and forest penciled out at agricultural values. Many of the West’s new landowners share two common traits: they are extremely rich, and they don’t live here. Remember those eight million acres of public land that are landlocked only if corner crossing is ruled illegal? The purchasing of a relatively small amount of strategically-located land can monopolize access to whatever public land lies behind it, creating a trophy ranch or a private hunting reserve out of land that belongs to all of us. The ultimate motivation is greed, pure and simple. And that really pisses me off.

Editor’s note: There's more to this story than space allows. For more, read part two, "Clouded Judgement."

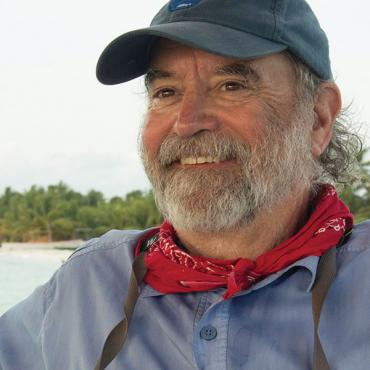

Retired doctor, former bush pilot, and prolific author E. Donnall Thomas Jr. has been writing about hunting, fishing, and access thereto since a time long before Montana landowners cared who crossed their land, at public corners or otherwise. His latest book is Traditional Bows and Wild Places.