Clouded Judgement

Picking up where he left off (see “At a Crossroads”), Don Thomas dives deeper into the muddled mindset behind the corner-crossing case in Wyoming.

In the first part of this series, we reviewed the technical aspects of the complex corner-crossing issue, and introduced a groundbreaking Wyoming case in which four hunters were charged with trespassing after crossing from one section of public land to another, even though their feet never touched private ground. Now we’ll explore that case in detail and consider its long-term implications for those of us in Montana.

As previously described, in October 2021, a Carbon County, WY deputy sheriff cited four Missouri hunters with criminal trespass after they crossed at a corner between two sections of public land. Although the potential fine—$750—wasn’t going to send anyone to debtor’s prison, the charge also carried the potential threat of jail time. The hunters chose to fight the charge and pleaded not guilty.

In April 2022, a six-member Carbon County jury acquitted the four, surprising many observers in light of Wyoming’s entrenched anti-public-land sentiment and the power of the ranching lobby, which strongly opposes the legality of corner crossing. This verdict was quickly hailed as a major victory by public-land advocates around the West. As Brien Webster said on behalf of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers (BHA), “We are very pleased with the outcome today seeing all four hunters acquitted of all charges for this criminal case. We’re hopeful that we can avoid future scenarios of criminal prosecution of the public for attempting to access public lands and waters.” However, he did add one important caveat: “We realize, too, that this isn’t a precedent-setting decision, but we do see it as a step forward.” The Wyoming chapter of BHA eventually helped raise over $70,000 to help cover the hunters’ legal fees.

However, there was still more to come from the aggrieved landowner in the original case, recalling one of the late Yogi Berra’s twisted aphorisms: “It ain’t over ’til it’s over.” Demonstrating the same kind of petulance Montanans saw from James Cox Kennedy in the Seyler Lane access case, Iron Bar Holdings—the entity through which wealthy North Carolina businessman Fred Eshelman owns the private ranch property—filed a civil suit against the four hunters. Iron Bar claimed that the hunters’ actions had decreased the value of its property and demanded some seven million dollars in compensation, earning a resounding what the fuck? from public-land advocates following the case. The basis for the dollar figure, provided by a friendly appraiser, remains unclear.

Even the most conscientious outdoors enthusiasts face a devilish choice: concede access to millions of acres of land they own, or risk criminal charges and the lost time and legal expenses they entail.

Plaintiffs argued that the hunters had “committed a civil trespass” (as distinct from a Game & Fish violation) based on an area of ambiguity explored in the first part of this piece: ownership of airspace. Echoing language from the Seyler Lane case in Montana, plaintiffs asserted that “Iron Bar Holdings has a right to exclusive control, use, and enjoyment of its Property, which includes the airspace at the corner, above the Property.” They neglected to mention that the airspace above the adjoining public property cannot possibly belong to them. Do they need federal permits when they work on a fence between their property and public land?

The contentious issue of airspace ownership just keeps coming up. In 1997, an Interior Department attorney for the Rocky Mountain region declared it private on uncertain grounds: “Under common law the one who owns the surface of the ground has exclusive rights to everything which is above it.” Including airplanes, satellites, and the moon? His opinion even extended to stiles (a.k.a., step-ladders used to surmount walls and fences) such as the one the Missouri hunters used. “[The] stile would invade the airspace of the owner of the cornering private lands [and] constitute a trespass.”

As a pilot, I have always regarded the Federal Aviation Administration as the regulator of airspace. Official FAA policy states that aircraft should not operate at an altitude less than 400 feet above ground level except for takeoffs and landings. However, it also establishes an important exception in “sparsely populated areas.” Since virtually every corner I’ve ever wanted to cross lay in a sparsely populated area, one must wonder: if I can legally fly a Super Cub over a corner in the backcountry, shouldn’t I be able to step across it as well?

Although the DOI attorney’s opinion is just that—an opinion with little to support it other than a vague reference to “common law”—the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), which oversees many of the public lands involved in corner crossing cases, incorporated it into policy. In a 2013 statement on the matter, the agency wrote, “There is no specific state or federal law regarding corner crossings.” (True, but...) “Corner crossings in the checkerboard land pattern or elsewhere are not considered legal public access.” How the BLM got from common law to an unsubstantiated opinion to an edict preventing countless citizens from accessing land they own remains a mystery, especially since, in their own words, “There is no specific state or federal law regarding corner crossings.”

If I can legally fly a Super Cub over a corner in the backcountry, shouldn’t I be able to step across it as well?

Now back to Iron Bar’s civil suit. Originally filed in state court, the matter was moved to federal court at the defendants’ request since it involves federal property. At trial, defense attorney Ryan Semerad raised an issue that could have far-reaching implications for future corner-crossing disputes. In a July 29 filing, he asserted that “(Iron Bar Holdings) is now violating and has, at all times relevant to its claims in the Complaint, violated existing federal law... by unlawfully enclosing public lands.”

This position derives from the 1885 federal Unlawful Inclosures Act (UIA), specifically written to protect access to federal property. The statute prohibits, in part, landowners from blocking “... any person from peaceably entering upon... any tract of public land.” This law would seem to stand in direct contrast to the BLMs’ stated opinion. Iron Bar Holdings, Semerad continued, “is now violating federal law... by unlawfully enclosing public lands and/or by using force threats, intimidation...” Recall the harassment the four hunters experienced at the hands of Eshelman’s ranch manager.

Prior to that confrontation, the hunters found two fenceposts driven into opposing corners of the private land about three feet apart and joined by a padlocked chain that would physically bar anyone from simply stepping across the corner (the reason why the hunters had brought the stile). Neither post was attached to any length of fence, and their sole purpose appeared to be for inhibiting access. Interestingly, the same DOI attorney who issued the muddled opinion on airspace ownership cited earlier wrote elsewhere that when “...under the guise of enclosing his own land (a landowner) builds a fence which is useless for that purpose and can only have been intended to enclose the land of the government, he... is guilty of an unwarrantable appropriation of that which belongs to the public at large.” The fenceposts were removed after the hunters left in 2021.

Involved in the case since its earlier efforts to help offset the cost of the hunters’ legal defenses, BHA remained engaged and filed an amicus brief on defendants’ behalf in December 2022, emphasizing the significance of the UIA. The brief reads in part, “A private landowner with half the ownership of a corner does not have a veto over access by the owner of the other half of the corner—namely the federal government, and by extension, the people of the United States. No individual monied interest should have the right to restrict the public from stepping across the corner of one adjoining parcel of federal public land to another, commonly known as corner crossing.” The brief goes on to cite precedents deriving from the UIA and other situations—perhaps the first time the UIA has been used in court to support corner-crossing rights.

If anything is certain at this point, it’s that the corner-crossing status quo is a mess.

An 1893 case decided in the United States Supreme Court ruled against two irrigators who erected fences blocking access to 20,000 acres of public land. “In Camfield v. the United States,” BHA attorney Eric Hanson wrote, “the Supreme Court held that fences put up inches inside private land on the checkerboard border were unlawful.”

A 1914 appeals-court decision ruled that fences built along public land in a manner such that “not even a solitary horseman could pick his way across without trespassing” were illegal, since “all persons... have an equal right of use of the public domain, which cannot be denied by interlocking lands held in private ownership.” In a North Dakota case that same year, the court held that the UIA was “intended to prevent obstruction of free passage or transit for any and all lawful purposes over public lands.”

After citing additional precedent, BHA attorney Hanson concludes that “the upshot is that the UIA plainly prevents private landowners from prohibiting access to public land for lawful purposes, including the momentary crossing of private land/airspace at a corner to access another section of public land. A finding to the contrary effectively grants the landowner dominion of federal public land he does not own and that he has not paid for.”

The Wyoming Stockgrowers association has filed an opposing brief, largely focused on the argument that state law takes precedence in such matters despite abundant precedent to the contrary. At the time of this writing, the matter is scheduled to appear before U.S. District Judge Scott Skavdahl this summer.

No matter how the court decides, the degree to which the decision in either Wyoming case may establish precedent in other jurisdictions remains to be seen. Wealthy private landowners have plenty of money with which to engage attorneys, and we cannot expect them to go gently into that good night.

If anything is certain at this point, it’s that the corner-crossing status quo is a mess. Even the most conscientious outdoors enthusiasts face a devilish choice: concede access to millions of acres of land they own, or risk criminal charges and the lost time and legal expenses they entail even in a best-case outcome. BHA, the organization that has taken the lead in the issue, is currently awaiting the outcome of the pending court case before advancing any specific policy. BHA President Land Tawney acknowledges that while federal legalization of corner crossing on the land it manages would help clear up the confusion among different states, changing laws at the state level would respect precedent and be more politically realistic.

What would favorable resolution of this conflict mean for Montanans? Look at the National Forest map of any nearby area containing a checkerboard land-ownership pattern—the Custer-Gallatin National Forest in the Crazies, the area west of Emigrant in Paradise Valley, or the northern Bridgers, for example. Note the green (public) squares that don’t touch a road but share a corner with one that does. There are a lot of them, too many for me to count without straining my eyes or making another pot of coffee. They belong to you, but you can’t get there legally. Comprehensive legislation to legalize corner crossing would finally solve that problem, expanding outdoor opportunities for all of us and obviating the need for endless expensive litigation that wastes money, which could be used for better purposes.

Hasn’t that time finally come?

May 26, 2023: Corner-Crossing Update

On May 26, Federal Judge Scott Skavdahl issued an important ruling in the case. This ruling came down—wouldn’t you know it—a day after the O/B summer issue, with the above article, went to press. The judge dismissed landowner Fred Eshelman’s $7 million civil suit against the four Missouri hunters accused of trespass after they crossed from one piece of public land to another at a corner without touching his property. Citing the 1885 federal Unlawful Inclosures Act, the judge also ruled that, “Corner-crossing on foot in the checkerboard pattern of land ownership without physically contacting private land and without causing damage to private property does not constitute an unlawful trespass.”

While this ruling may be subject to appeal, it has significant implications for access to the 8.5 million acres of public land currently landlocked by private property. Commenting on the ruling, Backcountry Hunters & Anglers president Land Tawney stated, “Today was a win for the people, both in Wyoming and across the country. The court’s ruling confirms that it was legal for the Missouri Four to step from public land to public land over a shared public/private corner.”

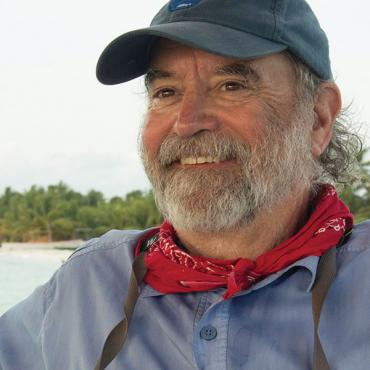

Retired doctor, former bush pilot, and prolific author E. Donnall Thomas Jr. has been writing about hunting, fishing, and access thereto since a time long before Montana landowners cared who crossed their land, at public corners or otherwise. His latest book is Traditional Bows and Wild Places.