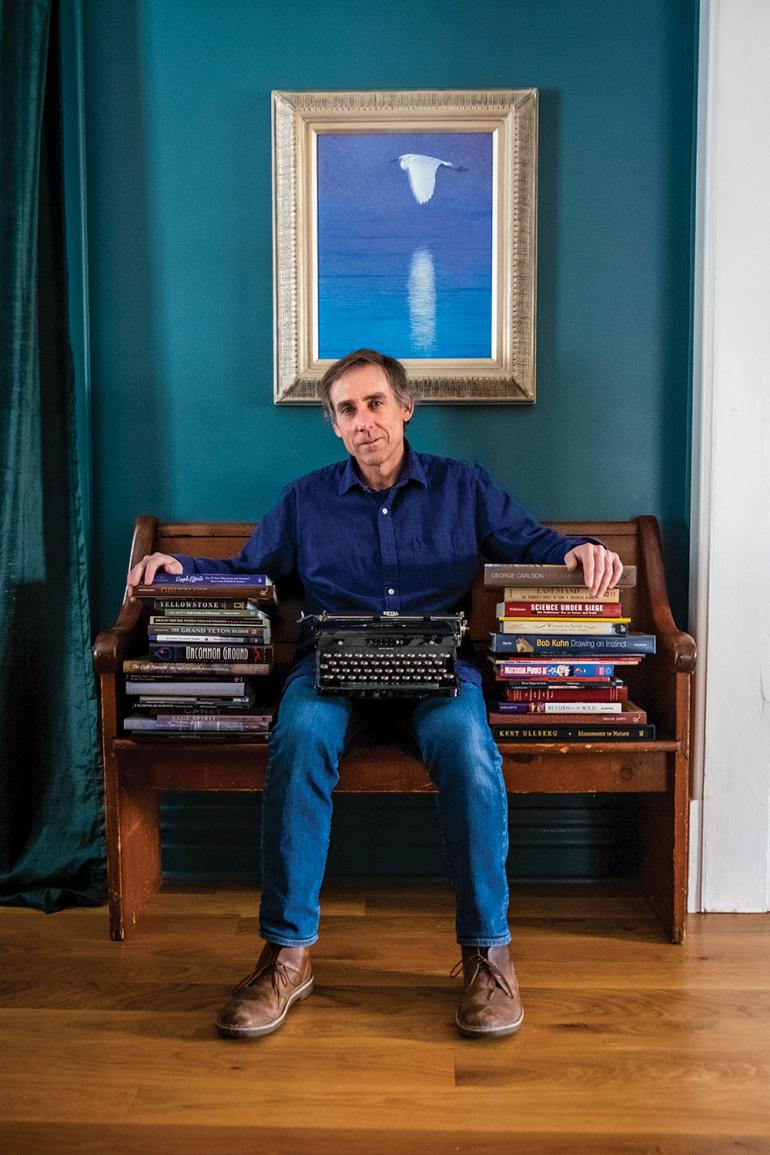

Where the Wild Things Are

Todd Wilkinson's conservation credo.

When Todd Wilkinson sets his sights on the controversies converging on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the environmental journalist and author draws a bead on public land: why we celebrate it, why we covet its wild heart, and how he pinpoints truth while probing the narrative of conservation across the American West.

“It’s different east of the Mississippi,” he says, setting the Greater Yellowstone’s wildlife habitat against regions with less public land, like the lake country north of Minneapolis where he hunted, fished, and canoed through his boyhood. The son of restaurateurs, he also played outdoor hockey, ran a trapline, and was “rabid about being outside.” But by 1982, the kid who slapped pucks on pond ice landed in Yellowstone National Park, working two summers through college in Canyon Village. “Public land was a game-changer in how I think about what makes this country special,” he says.

Early in his career, while reporting for the City News Bureau of Chicago, he adopted a rigor for fact that eventually sent him back west, and into the lap of science. Drawn to settle in the Greater Yellowstone area, he globetrotted on assignment for national newspapers and magazines, penned a longstanding column on the New West, and wrote books that bare science at the crossroads of politics, personality, and environment. World travel and diverse reporting showed the consummate career journalist that not everything can be measured in fact; truth is cobbled from patterns across time, across place, filtered through lenses of culture and experience.

“I’ve been a journalist for 37 years,” he says. “My thinking about conservation in the region has evolved dramatically.” From chronic wasting disease to bison to the rise of the recreation economy, Todd has reported on the plight of a threatened planet from his perch in a place still clutching a rare semblance of wildness.

“Wildness is defined by where the wild things are,” he says, schooling himself on the science that spins their stories over complicated terrain—their habitats, their habits, the people who hunt them or defend them or influence their movements across the borders and thresholds of politics and place. In 2017, he founded Mountain Journal, an online forum devoted to examining “the intersection of people and nature in America’s wildest, most iconic ecosystem.” Writing persuasively, prolifically, he parses trends in population growth, recreation pressure, and climate change to translate the onslaught of information about the threats pressing in on habitat crucial to the region’s wildlife.

“As a journalist, one asset I have is that I’ve been around,” Todd explains. “I read so many studies, I see the trend lines, I see what’s written elsewhere.” With a firm grip on his early rigor, he clarifies fact by honing in on sound science: data screened through the process of peer-review so it stands above muddier messaging more susceptible to manipulation or interpretation. Sound science, Todd says, pushes insight beyond he-said, she-said journalism: “Its agenda is to present evidence that can take scrutiny.”

It’s an examination necessary to understand the pressures poised to devastate our wild lands and fragment wildlife habitat. Todd identifies critical trends: an erupting population and intensifying development, especially in valleys where preferred locales for human habitation coincide with tracts of vital wildlife habitat because they are low, have water, and provide crucial winter range; record inundation of visitors introducing unprecedented patterns of change in public land use; and recreation pressure so heavy it forces animals, like elk, to alter seasonal movements across the landscape, often from public onto private land.

“In 2017 there was already a profound growth issue,” Todd says, noting spillover effects of affordability that impelled workers in Jackson Hole to drift into Teton Valley. “There was the uncontrolled bulge of Big Sky.” By 2019, Todd explains, the population of the quaint Gallatin Valley of just over 100,000 was projected at a three-percent growth rate to double to the size of Salt Lake City proper within 24 years. Then double again to the size of Minneapolis proper in less than 50 years. “And that’s a conservative estimate,” he adds. “Since then, Bozeman and the Gallatin Valley have actually grown 4-5 percent.” Connecting the dots in similar fashion from Idaho Falls through Rexburg, Teton Valley, Jackson Hole and south to Star Valley and Afton, Wyoming—a corner of the Greater Yellowstone with over 220,000 people today—he asks, “What happens when all this fills in?”

Definitive about his role, Todd is neither advocate nor activist but a self-professed stickler for sharing science.

Compounding the carve-up of habitat by growth and development is climate change, he adds, which alters the hydrology of our region: drought that spawns algal blooms, drives forest fire, and exhausts municipal water supply; grasslands encroaching to force montane forest refuges off the mountain. From expansive population growth to extreme weather, Todd has witnessed patterns both overseas and closer to home where large mammals have been lost. “The wildlife is not there,” he says, “and it won’t come back.”

He brings his witness to bear on home turf, declaring that “Yellowstone National Park is an illusion in some ways.” Founded across a high plateau that was never big enough to support large populations of prairie species—elk, wolves, bears, bighorn sheep—its vaster habitat is increasingly invaded by pressures on wildlife. “They want lower land to move to,” he explains, “and we’re killing them for it.”

By 2016, while penning captions for a National Geographic book on Yellowstone Park, Todd saw the need for tighter focus on macro-trends throughout the region. He launched Mountain Journal to improve public understanding of the stakes. The sanctity and ultimate endurance of an ecosystem, he says, is about more than where the wild things are; it’s about how they move, and why.

“Migrations are the transport of energy,” Todd says, drawing vectors of life from the sun, through plants, into prey, to feed predators and scavengers. He explains how vegetation, long-adapted to browsing, sustains generations of ungulates etching their trails like signatures across artificial boundaries and borders.

He continues: “We have nearly a dozen elk herds that cycle like bicycle spokes into the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, that function like lungs that breathe. You can take this map and do it for mule deer. You can do it for pronghorn. Migrations are superstructures that let us think in a transboundary, visionary way. They tell us what animals need.”

What they need, Todd believes, is people talking: major players of the Greater Yellowstone region coordinating with an engaged public to strategize for a shared fate across the labyrinth of public and private parcels that bound their landscape and their livelihood. Through methodical, clarified journalism, Todd cinches us in toward a common morality, toward an honest assessment of current trends that are undeniable. “We have an exceedingly rare thing in our hands, this wildlife legacy,” he says. “We have numbers of large mammals, still moving. Are we willing to modify our behavior to hold onto it?”

Definitive about his role, Todd is neither advocate nor activist but a self-professed stickler for sharing science. “I’m pro-enlightenment,” he says. “I want to give my readers the best available information to make informed decisions.”

World travel and diverse reporting showed the consummate career journalist that not everything can be measured in fact; truth is cobbled from patterns across time, across place, filtered through lenses of culture and experience.

But there’s a trick. “Information can be a pebble in the back of a shoe,” he says. “It’s always there, grinding away at your conscience. You have to deal with it.”

In his newest book, Ripple Effects: How to Save Yellowstone and America’s Most Iconic Wildlife Ecosystem, Todd drops the pebble. Radiating to the horizon, the lines that transfer energy through ecosystems from the heart of where we live can move ideas from concept to conscience, driving culture toward a shared vision that affects change. “Science reminds us what’s out there worth protecting might be invisible to most of us,” he explains. “Then it becomes an epiphany.”

From ripple to revelation, the veteran journalist is humbled by a home ground worth fighting for, rabid now to be in this place, to revel in its wildness, to reveal it.

To see Todd’s work, check out mountainjournal.org or toddwilkinsonwriter.com.