Walking the Walk

Author and angler Thomas McGuane shares his thoughts after a lifetime in Montana.

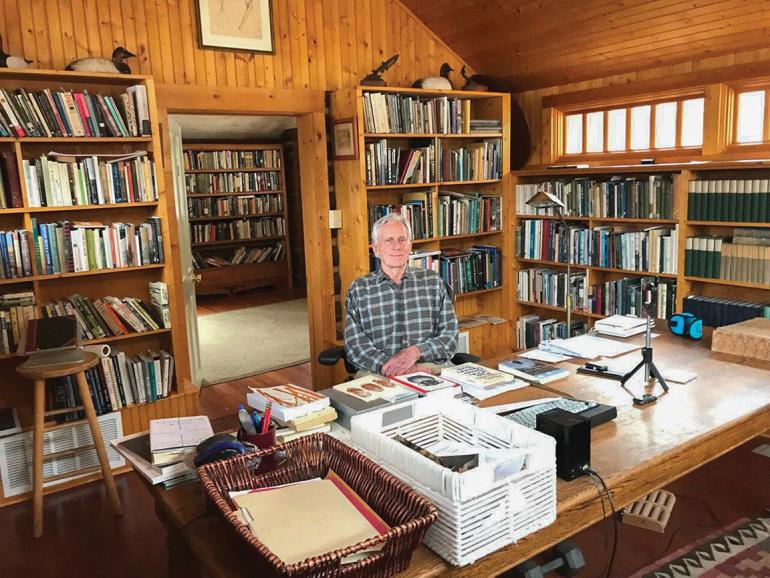

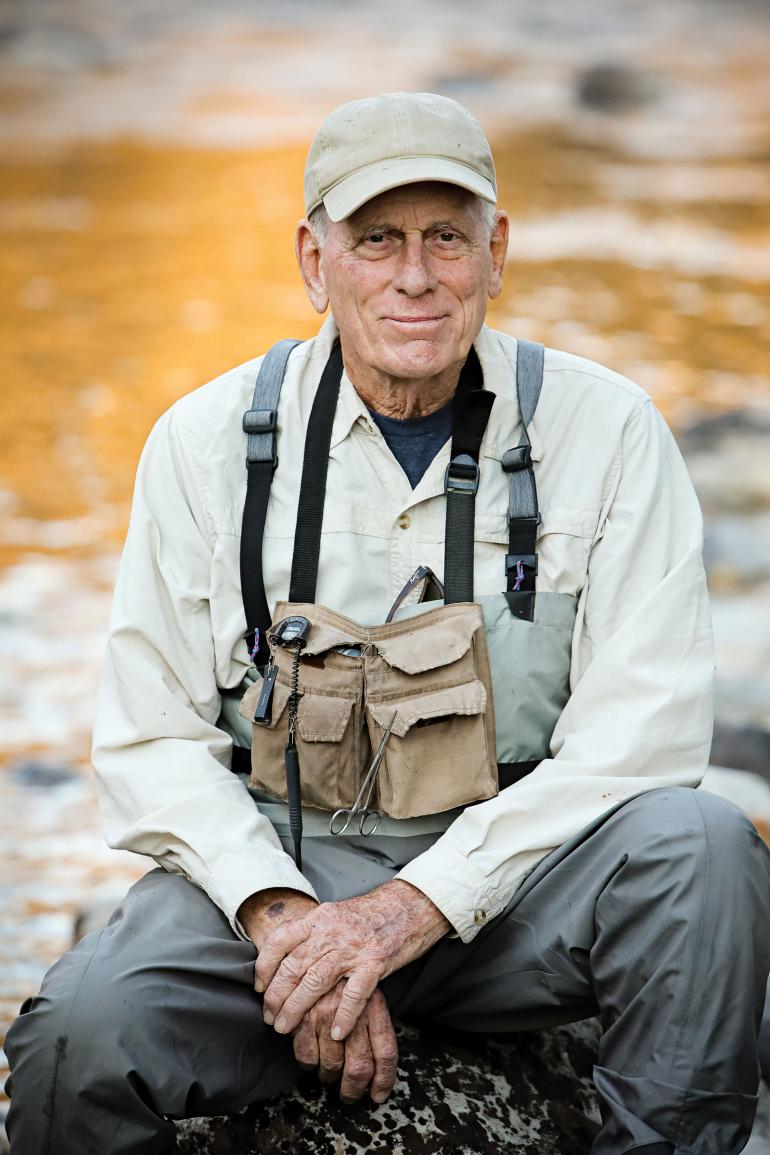

Renowned writer Thomas McGuane once wrote, “I've spent as much of my life fishing as decency allowed, and sometimes I don't let even that get in my way.” He’s been an angler for almost 80 years, just about as long as he’s been a writer, and the two activities define him equally. He’s also a hunter, cattle rancher, and horseman, having won several cutting-horse championships. But whether he’s an angler, cowboy, or writer first is no matter—McGuane gives his readers everything in the way of history, stories, advocacy, and pure love for the outdoors. His experiences in Montana, where he has lived since 1968, form a backdrop for his extensive collection of novels, screenplays, short fiction, and essays. One recent sunny day, McGuane settled into a chair at his McLeod ranch to answer questions about his many years as a Montana writer. Looking out on a curve of the Boulder River sweeping around his home, he discussed the evolution of his writing career, life under the big sky, public-land access, and how things have changed over the last 50-some years.

O/B: How does living in Montana influence your writing?

TM: It’s my only experience, really. I got here in my mid-20s, and now I’m in my mid-80s. I wasn’t really welded to a place until I moved here, because my father moved around for jobs when I was young. My family is from Massachusetts, but they moved to Michigan and I kind of grew up there. In high school, I started working on ranches in southwest Montana. I always knew I wanted to live out west. As soon as I got out of graduate school in 1968, I just came here, and that was that.

What’s the biggest challenge you’ve faced in your writing career?

Believing that I would eventually be published. I wrote daily, sometimes all day long, for at least 10 years, without any reward. Certainly my parents thought I had lost my mind, and I was lucky because I got fellowships to study. That sheltered me from reality for a while. By my late twenties, I’d really run out of schemes. Unexpectedly, my first book was accepted by Simon & Schuster. But it was really a close call, and I was facing the reality that it might never happen.

What is your daily writing regimen?

I try every day. It’s harder as I get older—I don’t have the fluency I had as a young writer. But I’m still writing; I recently renewed my contract with The New Yorker, writing short stories, which is less burdensome than writing novels. Sometimes it goes well, sometimes I flee. It’s easier in bad weather.

What are your best and worst pieces of writing?

I don’t really know, but I think my best writing has been my short stories. I think my worst writing was some of my failed screenplays.

What is your responsibility to your readers?

To be interesting, as Henry James said. But I also need to maintain an integrity of truthfulness about what I’m saying, even about the lives of fictional characters. That’s an intentional limitation, because it keeps me from arbitrary sensationalism.

Were you a bookworm as a kid?

Yes! I was an escapist in a sense, because I wasn’t a good student. Libraries were a huge deal for me. My junior-high graduating class (of eight) had a bookmobile, which I loved. I’ve been a library hound all my life. I love libraries. I love books.

Do you have a favorite book?

A lot. Don Quixote, Dead Souls, A Farewell to Arms, Life on the Mississippi, Moby Dick... and the work of Anton Chekov.

Do you ever write by hand?

Yes, but I have really bad handwriting. Computers are a gift.

In general, which do you prefer as a means of communication from the outside world: TV, newspapers, or the internet?

I read five newspapers every day, online. I do kind of miss physical papers, although they really pile up.

What profession other than writing would you like to participate in, and why?

That’s a tough one. Probably teaching. I’ve never had much of a plan in life, no scheme for a lifelong career—as evidenced by the fact that I flunked out of college twice. But later, I ended up on the dean’s list and got a scholarship to Yale, then another fellowship to Stanford. So I had about four or five years when I was just on scholarship. In that period, I became not a bad scholar. I still have a scholarly interest in literature. I probably would have enjoyed teaching literature.

What are your main hobbies or avocations?

Fishing is my favorite thing, both flats fishing and fly fishing. It has a contemplative quotient, with the water going by, tunnels of trees... I can just go out there and not think about my character flaws. Horses were also a big part of my life for a long time; I rode constantly until I was about 75. And bird hunting. I run my dogs now, I don’t bird-hunt much—but I still take them out on these fake hunts. The natural world is my religion.

How has fly fishing shaped your life?

Profoundly, because from the age of six I’ve been a fisherman, and I’ve been a fly fisherman since I was 14. I’ve really let it lead me around by the nose all my life. In fact, some people say I became a writer as a front for fly fishing. I think I love literature enough for that not to be true, but when I travel to a new city, the first thing I do is hit the fly shops and bookstores with equal energy. And that’s really never changed.

Why are you drawn to fly fishing?

My father and grandfather were fly fishermen, and I guess it just seemed like a more poetic way to fish, in which you were more embedded in nature than some other ways. And it’s an interesting type of fishing, because casting is interesting—it’s something you can improve on all your life.

Let’s talk more about Montana for a minute. What changes have you seen in the outdoor culture since you’ve lived here?

The only outdoor culture I know much about is fishing, and it’s become more crowded. There are greater challenges to the health of fisheries that no one seems to understand. The decline of brown trout in the Big Hole is very concerning. The main thing is that there are really too many fishermen, especially on the Madison. It puts extraordinary pressure on the fish. So I think they’re going to have to figure out a way to control that. In terms of how it’s changed in the over half-century that I’ve been fishing in Montana, it’s become necessary to find some out-of-the-way fishing—maybe less good fishing—to have the quality of peace and solitude that a lot of fly fishermen seek.

Now looking at the bigger picture, how have things changed in Montana as a whole since you’ve lived here?

It’s become more polarized. It was always a little bit polarized about who was local and who was not, but now that the internet and media have brought all these culture wars into the state, Montanans are worried about things we’ve never cared about before. I can’t imagine the Montanans of the late ’60s when I moved here gave a damn one way or another if they had a drag show on the Hi-Line. We had a more moderate electorate; we were a state of ticket-splitters, and we had great, reasonable, high-powered individuals like Mike Mansfield representing us. So from my point of view, it’s been a long haul to the mega-right that’s now really present in Montana.

Also, access issues have become tenser, in some ways. This is a byproduct of population increase. When I first lived in Montana, you could go anywhere you wanted. There wasn’t a lot of this private-property mania, and most people were happy to let you fish or hunt on their land. We now have so many second homes or out-of-state landowners who are concerned with their property being used or abused in their absence, and they’ve become more militant about boundaries, property use, and access to resources—partly because they’re not there. And they’re worried about what’s happening. But the good thing about having so many hunters and fishermen in the landscape is that they’re real stakeholders in that land, so I think they want the best for the place. They’ll fight for that.

Do you feel you’ve had any influence on the direction of these changes?

Well, originally, I was a real avid proponent in my writing and other work for catch-and-release fishing, which was not normal in the late ’60s. Most trout fishermen had a stringer. I’m not really a political writer, but I’ve always cherished my love of Montana wildlife and wildlands. My anxiety about subdivisions is visible in my work. We have a conservation easement on our place, and I’ve spoken out a lot about that in the past. So I guess that’s been my influence on things.

Talk a bit more about public-access issues.

There’s a movement afoot to restrict public access. I’m a big fan of the Montana Stream Access law, and that’s always under attack. There’s so much checkerboard land held inside of large land holdings, very often by people who don’t live in Montana, that I believe in corner-crossing—it’s very controversial now. It’s already won its case in Wyoming, and the United Property Owners of Montana are fighting it bitterly. The problem is that there’s a legitimate desire to know who’s on your land, but very often we have large ranches held by out-of-state entities and they have hundreds of thousands of acres with public lands locked up inside them.

What sort of work are you involved in to help protect water and public access?

Not much of anything, publicly. I support a number of organizations that are protecting access, but in terms of going out there and campaigning, I don’t do that. I like to think my life and my writing show good practices... I walk the walk.