Burning Down the House

The sky is dark. It’s midnight, under a new moon; were it not for the shimmering stars overhead and a wan glow from town below, this grassy hilltop would be in utter blackness. There’s just enough light to make out shapes, dozens of them, huddled on the ground. One of them rises. A murmur begins among the crowd, growing louder until it reaches a deafening crescendo, then stops. The shape raises its arms and bellows, “LET IT BURN!”

The name and inspiration come from Burning Man, the famous gathering in the Nevada desert, but the spirit is straight out of the Old West.

Matches are struck, the tiny flames tossed forward, and a conflagration erupts. The illumination reveals a massive log home, bedecked with the typical dormers, vaulted ceilings, and arched entryways. As the logs catch fire amid growing flames, the crowd disperses, dancing around the gargantuan blaze. It’s a merry, celebratory scene, reminiscent of a maypole dance—which, in fact, is exactly what it is. The participants smile, hold hands, and sing, exuding a sense of hope and promise, looking forward to new and happier days ahead.

This, for those new to the area, is Burning Mansion, an annual springtime celebration of western culture and the change of seasons. The name and inspiration come from Burning Man, the famous gathering in the Nevada desert, but the spirit is straight out of the Old West. It’s a call to freedom, to the wide-open landscape of Old Montana, before Big Sky Country became a vacation village for the rich and famous, whose sprawling jack-leg fences partition the land like pastures, corralling people into smaller and smaller spaces. The bonfire is the culmination of five days of festivities, leading up to May Day and the “Big Burn,” which illustrates in dramatic fashion the overarching theme of the event: Out with the new and in with the old.

History

Like all good ideas, Burning Mansion was born in a bar. Three longtime Bozemanites—Cam Bustebal, Ben Bernin, and Mel Tingwood—were sharing a pint at the Haufbrau in 2016, after a prolonged mushroom trip at the Fox Creek Cabin. On the way out, they’d stopped to wash off their fake dragon tattoos in S. Cottonwood Creek. The landowner, a recent transplant from San Francisco, told them to get the hell off his property. “We thought about kicking the guy’s ass,” Bernin says. “But after our transformative experience at the cabin, we didn’t want to get violent. So we decided to burn an effigy of him instead.”

“It seemed perfect,” Bernin adds. “Then during the ceremony, we channeled Ed Abbey into our spirit circle. He told us we were being pansy-asses and to burn down the bastard’s house.”

Critics say the burners are deluded, that they’re fighting a losing battle, that the super-rich are here and here to stay.

So, after checking with the neighbors, all of whom agreed that the newcomer was a “first-rate ass-hat,” Bernin set the landowner’s 6,000-square-foot structure ablaze, then high-tailed it to a wildlife refuge in Oregon, at the time occupied by a few of his buddies, to wait out the statute of limitations. When he returned, Bernin had the plans for Burning Mansion all laid out. “Despite our humble beginnings and illegitimate status,” says Bernin, “we’re doing as much good for the people of Bozeman as GVLT.”

Principles

In keeping with the spirit of both Burning Man and May Day, Burning Mansion promotes community and communal effort. “Everyone chips in,” Bernin explains. “Some people case the joint, others create diversions for the cops. And everyone helps start the fire.” Radical inclusion, another key Burning Man ethic, also applies. “Burners come from all walks of life,” Bernin says, “from repressed pyromaniacs to quixotic college kids to soft-spoken wind whisperers who meditate during the entire blaze.”

Regardless, the event is all about authenticity and non-commercialization, about getting back to our roots and the pure freedom of non-materialized nature. After pre-registering to receive a Burning Mansion t-shirt, that is. (“We do have a small amount of overhead that needs covering,” says Bernin.) No smartphones are allowed. Nor is cash. For the entire event, the barter system applies—wild game and garden vegetables are purchased with old snowshoes, which are traded for hand-tied flies, shed antlers, or condoms. “Everybody brings their own form of currency,” Bernin says, “and it all works out fine.”

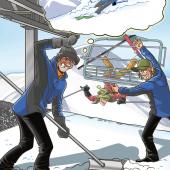

Also pre-eminent is the concept of self-reliance. When the cops come—and they inevitably do—it’s every man for himself. The thrill of the chase keeps many fitness buffs coming back, year after year. “There’s just nothing like the physical stress of five cops on your tail while launching over flaming floor-joists,” says one burner. “By comparison, that Spartan race is a freakin’ family 5k. After my first burn, I got a tattoo of a burning mansion on my right calf.” Another burner thrives on the ideological intensity: “Eating elk jerky in the woods and then roasting a Locati abomination? It makes me feel like freakin’ Che Guevara.”

Environmental Responsibility

Each year, a home is carefully selected based on a strict set of criteria, including size, visibility from afar, and nearby escape routes. The burn itself takes place on or around May 1st, when the ground is moist, to prevent the fire from spreading to adjacent forests—or, God forbid, any normal houses that may be in the vicinity. Burners ensure that no people or pets are in the building at the time of combustion—an easy task, as these houses are seldom occupied for more than two weeks out of the year.

Leave-no-trace, however, is an ongoing battle. “It’s not logistically possible to clean up the charred wreckage of an 8,000-square-foot cabin,” explains Bernin. “Besides, the insurance companies seem to do a good job with that stuff.” And in the end, it’s a net-zero carbon footprint. To offset the toxic emissions from the blaze, participants reduce their fossil-fuel consumption by showing up on bicycles. Afterward, they’re donated to the Bike Kitchen, which serves as a “cleaner”—the burner bikes go out to children, homeless people, and the few remaining MSU students lacking trust funds, leaving no forensic ties back to the burners themselves.

Recently, spotted among the revelers were several Bozeman and Big Sky elites: lawyers, realtors, and developers disguised in Carhartts and muck boots, “slumming it” as fellow insurgents in the war against gentrification.

Security

Burning down an out-of-state venture capitalist’s $10 million third home may not be immoral, but it is illegal—even in this enlightened age. Therefore, all burners must swear an oath of secrecy, the violation of which results in forfeiture of all one’s outdoor gear and apparel. Several members have been caught, but none have squealed—or even been prosecuted, for that matter. Evidence is hard to collect, and juries are sympathetic. Who wants to imprison a freedom fighter?

Bernin himself maintains a network of secret hideouts and an advanced communication system for sharing information with participants. “The guy’s an enigma,” says local sheriff’s deputy Jess Cantkachum. “We’ve run his name, nothing. Every time we get close, he slips through our fingers. And he’s torching trophy homes that everyone hates, so we’re not getting a lot of help from the local populace.”

Future

Recently, spotted among the revelers were several Bozeman and Big Sky elites: lawyers, realtors, and developers disguised in Carhartts and muck boots, “slumming it” as fellow insurgents in the war against gentrification. Which has many longtime burners wondering, has Burning Mansion jumped the shark? Has it become the cool thing to do, a source of status, thus violating the very tenets upon which it was founded?

“No way,” Bernin retorts. “Quite the opposite, in fact. A few years ago, John Mayer showed up, which raised some eyebrows. But the very next year, he lit his own house on fire! And he didn’t even have to hide afterward. We’re hoping that his noble act inspires other mansion-owners to follow suit and burn down their own monstrosities.”

Not everyone is on board, however. Critics say the burners are deluded, that they’re fighting a losing battle, that the super-rich are here and here to stay. To them, Bernin replies, “Who says you can’t go back in time, to recover something that’s been lost? The Dark Ages followed the super-advanced civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome, and that lasted for hundreds of years. All we’re after is a few dick-free decades. We want our kids to know the Montana that we did when we were young.”

As for the inevitable, and unfavorable, comparison to hippies, animism, and primitive rituals, Bernin brushes it off. “This is not some twisted Wicker Man shit. We’re not paganistic, just pragmatic. The mega-mansions aren’t sustainable. We’re simply doing our part for Montana. I think it’s time for everyone to ask him- or herself, what am I doing to protect this place?”