Following the Footsteps

The long history of hunting in south-central Montana.

As hunters around the region take to the mountains and prairies for another season of big-game harvests, it’s a good time to reflect on our area’s history of subsistence hunting and the legacy of sustainability that we have inherited as contemporary Montanans.

Ancient Sites

Two of the oldest and most noteworthy archaeological sites in the western hemisphere are located just east of Bozeman. They both provide evidence of the highly skilled and capable hunting cultures that thrived in the harsh climates and terrains in this corner of the state.

Exquisitely knapped chert spear points, and a multitude of other handcrafted stone and bone tools from the Anzick site in the Shields Valley, mark the earliest evidence of indigenous people in the state. The vast collection of burial artifacts indicates that the family living at the site hunted a stunning array of mammals, including miniature camels, woolly mammoths, and Bison antiquus—a gargantuan ancestor of the modern bison. Those exotic animals disappeared at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, when warming climate caused their foundational food source—leafy forb plants—to fade away and be replaced by grass, creating an expansive grassland ecosystem. This massive ecological shift gave rise to an era of bison dominion that lasted over 10,000 years, and provided the food and textiles for the Plains Indian way of life.

Like rivers of blood, bison flowed across the land with their noses pointed into the blowing wind, prompted by gusts and guided by smells of grass- and water-filled valleys.

Situated at over 10,000 feet and located about 100 miles southeast of the Shields River on the Beartooth Plateau, dozens of ancient ice patches are slowly dissipating and revealing that native hunters expertly utilized these high-mountain zones to harvest migratory herds of bighorn sheep, elk, deer, and bison. A research team at MSU has been studying these ice patches for over a decade, and they’ve discovered through happenstance that modern bow hunters are still utilizing the same ice patches in the autumn to lure in and harvest elk. Other findings include the oldest artifact ever recovered from an ice patch outside the Arctic: a 10,000-year-old atlatl dart that is now part of a traveling ice-patch exhibit. A permanent exhibit is slated to be installed at the Draper Natural History Museum in Cody, Wyoming, in 2024.

Migrating Bison

Although bison culture reigned supreme across the Great Plains since the beginning of the Holocene (the current geologic epoch), the heart of that way of life was in central Montana, where the largest and most resilient herds migrated north and south throughout the year. Like rivers of blood, these massive herds flowed across the land with their noses pointed into the blowing wind, prompted by gusts and guided by smells of grass- and water-filled valleys.

The central Montana geographic feature known today as the Judith Gap marks a pinch-point on the land, where southward migrating herds of bison were funneled into a bottleneck valley and diverged into either a western path that led to Paradise Valley, or an eastern route that directed them towards the Bighorn and Little Bighorn river valleys, then along the eastern front of the Big Horn Mountains. The Judith Gap itself is located between the Little Belt and Big Snowy mountains, where the wind blows every day.

The eastern route is now a paved road known as the “Old Buffalo Trail,” which connects to the Yellowstone Valley in Laurel, just north of the confluence of the Clark’s Fork and main-stem Yellowstone. The Nez Perce also followed this well-known trail through the Judith Gap on their flight to Canada in 1877.

Rock lines were effective as fences because of the poor eyesight of bison, and their basic instincts to stay within a safe space and to avoid overstepping onto uneven ground.

The western route that led bison to the Yellowstone Plateau straddled the Crazy Mountains, then went directly through the wind tunnel known today as Paradise Valley. As these herds seasonally made their way back and forth towards the Yellowstone high country, they would pass through buffalo-jump sites marked by long lines of large, deeply-imbedded stones. Decades of research and careful documentation by local archaeologists have revealed over 60 miles of rock drive lines concentrated in a hunting zone about 20 miles long and 10 miles wide. These rock lines were used as fences to herd galloping bison toward nearby cliffs, where they would be wounded and subsequently harvested en masse. The rock lines were effective as fences because of the poor eyesight of bison, and their basic instincts to stay within a safe space and to avoid overstepping onto uneven ground. Drive lines are commonly found at many buffalo-jump sites in Montana, but the large-scale landscape engineering constructed by indigenous hunters in Paradise Valley displays an unprecedented level of permanent infrastructure for hunter-gatherer-traders. Within a global context, only some 8,000-year-old gazelle-hunting sites in modern day Syria can compare.

The miles of aligned and embedded rocks also correlate with Apsáalooke (Crow) oral traditions, and show a gradual sophistication in how native hunters utilized the buffalo jumps. Although it’s difficult to accurately age the lines, it appears that the oldest ones directed groups of galloping bison directly over the cliff—causing mortal injuries to the lead cow, and residual social disruption to the entire group. The most recent rock lines were made within the last 200 to 300 years, and mark paths that run parallel to the edge of the cliffs, rather than directly over.

As local archaeologists puzzled over these recent parallel rock alignments, Apsáalooke historians recognized what they were. During a site visit to the lines in the fall of 2022, tribal cultural experts informed researchers and other historians that their ancestors understood the value of keeping the lead cow alive when hunting bison, so the parallel rock lines protected her from falling over the cliff. Yet, the lines’ close proximity to the cliff face and the large number of animals running alongside it inevitably led to many bison near the end of the herd drifting over the line and off the cliff, creating an efficient, practical, and respectful way to hunt the sacred animals.

The Tukudika were famous for perfecting the art of fashioning powerful and long-lasting bows from bighorn sheep horns.

The accompanying topographic map provides the location of the lines identified so far, although ongoing work continues to identify lines and other stone sites. The map also indicated where the sites of rock cairns, stone circles, lithic material zones, and bison kill sites were discovered. Ceremonial prayer sites were also part of the harvest-zone landscape.

River of Elk

Along with migrating herds of bison, expansive herds of elk also traveled through Paradise Valley, following the Yellowstone River to its source at Yellowstone Lake and beyond. These elk were an extremely important resource for all native people, as they were a rich source of high-quality meat, and their hides were preferred over bison for use in clothing and hand drums. Their two ivory eye-teeth are also some of the most prized material objects in Apsáalooke culture, and the tribe is famous for its traditional dresses that are typically adorned with hundreds of ivories.

Sheep Blinds

Bighorn sheep were plentiful throughout Paradise Valley, but most evidence of sheep hunting is documented just south of Yankee Jim Canyon, close to the Yellowstone River. It is here that a three-foot-tall rock wall, estimated to be around 1,200 years old, stretches over 100 yards across a mountainside. The wall was created and used as a hunting blind for harvesting sheep, and it still stands strong and intact.

The sheep were also year-round residents of the plateau, and became synonymous with both the region and with the hearty bands of Tukudika (Sheep-Eater Shoshone), who wintered in the Yellowstone high country. This hearty tribe got its name due to both diet and locale, which differed from the bison-eaters (a.k.a., Eastern Shoshone) who lived around the Wind River and Big Horn ranges in the winter. The Tukudika were also famous for perfecting the art of fashioning powerful and long-lasting bows from bighorn sheep horns. This process required soaking the horns in hot water to soften them, then cutting them with obsidian knives, and form-fitting them with sinew and glue to make them ultra-resilient.

Learning about the Upper Yellowstone region’s deep history gives us greater insight into the true nature of this place and allows us to plan for an environmentally resilient future that honors our land and our wildlife. Keeping our region magical and rich with a vibrant and healthy ecosystem is worthy of our efforts—for ourselves and for future generations.

Dr. Shane Doyle, Apsáalooke, is a scholar and community advocate who works as a cultural consultant in Bozeman.

Returning Bison to the Prairie

by Corey Hockett

As a result of the ever-expanding human footprint, bison have been cut off from much of their historical range. In fact, outside of Yellowstone, there are only two other truly wild herds left in the Lower 48. In all three cases, the bison’s home ranges overlap with cattle-ranching operations, resulting in some interesting management strategies for the native megafauna.

The crux of the matter is that bison can be classified as either wildlife or livestock. On one hand, this limits their ability to roam as they once did. But on the other, it opens up opportunity for landowners to use grazing leases for bison instead of cows, as has been the case historically. Some organizations are using this approach to get bison back on their historic range, and nowhere is it better exemplified than in Phillips County. In 2022, the BLM approved six allotments for American Prairie (AP) to graze bison across 63,500 acres of public land. While the animals managed under these permits are technically considered livestock, AP is treating them as wild as is legally possible. The bison receive a mandatory brucellosis vaccine and stay within the boundaries of the allotted permit, but AP’s vision is a landscape-scale restoration effort which includes fence tear-downs, connecting expansive ranges of historical habitat, and a managed bison hunt. It might be a departure from traditional ranching practices, but it’s within the legal bounds, and is thus far proving successful in putting bison back on the Montana plains.

Buffalo Jumps of Southwest Montana

by Dave Hemphill

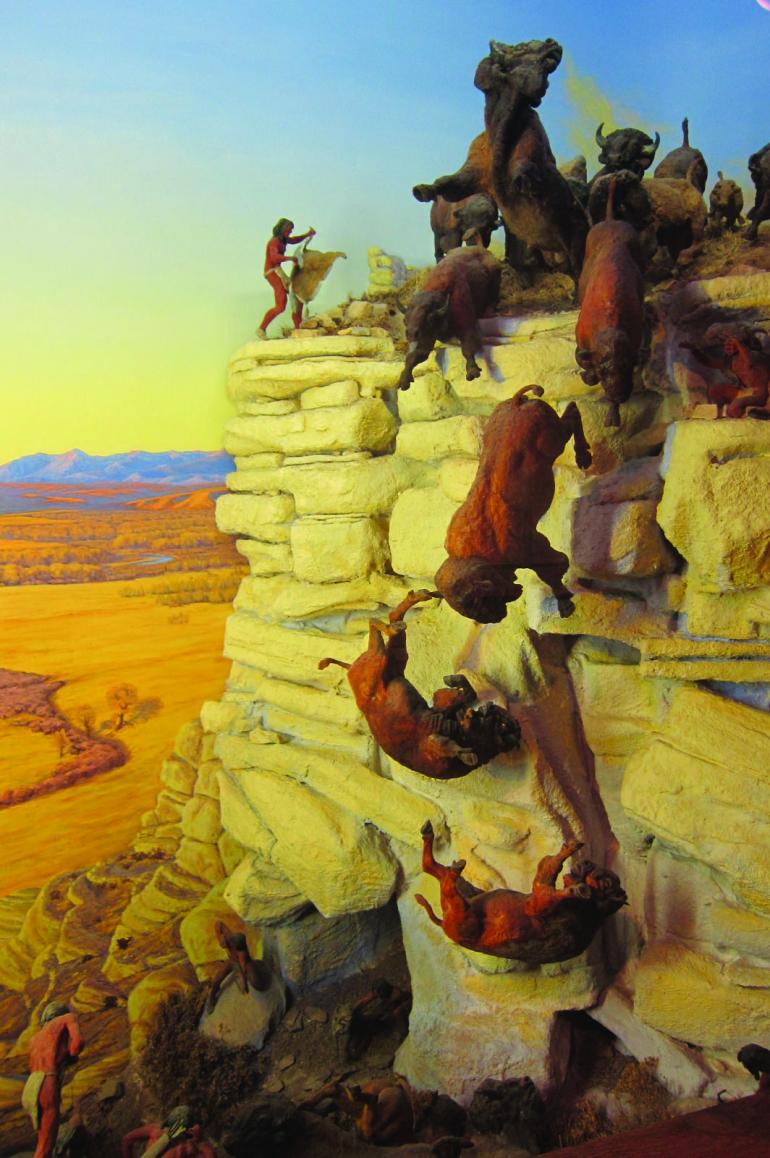

As the bison ran, frightened grunts and primordial bellows filled the plains. The air was sweaty and thick with the wallowing musk of bovine urine, feces, and perspiration. A cloud of dirt and dust, kicked up by thousands of thundering hooves, hazed the sun. The ground was alive as it pulsated and quaked under the tonnage of streaking animals.

Ahead of the stampeding beasts, a lone hunter, dressed in the hide of a bison calf, sprinted at the limit of his athletic ability toward a rock precipice. Hunters donning wolf pelts harassed and antagonized the herd from its fringes. Other tribal members, lining the creatures’ passage, whooped and hollered, waving robes and hides in the air. Just as the maelstrom of crazed animals reached the drop-off, the single hunter up front dove out of the way. Like a wave crashing into land with the momentum of an entire ocean behind it, the animals in front were shoved over the edge by the mass of the herd in the rear.

Long before horses and firearms arrived on the North American continent, indigenous people hunted big game. Since 4,000 years ago, American Indians used cliff-bands to harvest bison. But it wasn’t so simple as just chasing the large animals off a rock face, and then collecting the dead meat at the bottom. The locations were strategically selected; the hunts sophisticated and complex.

Known as the “runner,” a solitary hunter would cloak himself in a bison hide. Groomed from boyhood for the part, he was prized for his speed, endurance, and knowledge of bison behavior; and was entrusted with the role of leading the herd in the direction of the cliff. Piquing the interest of the herd’s lead bison by mimicking the distress call of a calf, he’d lure the animal toward the escarpment. The herd, known for following a leader, would start to move toward the jump en masse.

As the affair progressed, hunters dressed in wolf skins arrived on the flanks of the herd (legend has it that tribes learned to hunt bison by observing packs of wolves). These hunters, imitating the canines’ movements and techniques, would agitate and unnerve the bison, funneling them even closer to the cliff. When panic took over, and the herd broke into a run, other tribal members stationed along the route—referred to as “hazers”—would pop out from behind blinds; whooping, hollering, and waving their arms, adding to the hysteria.

While the bison charged toward the cliff, they built up a momentum that was impossible to stop. At the last possible second, the runner jumped out of the way into a predetermined crevice or onto a ledge (there are many accounts of lead runners missing their marks and leaping to their deaths). Moments later, on the hunter’s heels, the bison toppled from the edge, careening to the ground below.

Days later, the earth and prairie grass were stained red, saturated with the blood of the butchered animals. Hordes of flies buzzed about in a thick cloud, and mobs of bickering birds careened overhead. Mounds of burning guts and bones sent a dark, rank smoke into the air—by setting the unusable parts of the bison aflame, the tribe cleansed their hunting camp for the following season. The insects, scavengers, and stench made the site an unbearable place. Leaving for winter camping grounds was surely a relief. Packed with all they could carry, the tribe would hit the trail with enough food and hides to last an entire year.

In the humans’ absence, the land would reclaim the bison remains left behind, and the cycle would begin anew.