Go Deep

Caving, Montana-style.

Crazed subsets of people will always seek Earth’s most inhospitable environments: the jagged, ice-covered, oxygen-starved heights of the Himalaya; the terrifyingly sheer granite walls of El Capitan; the freezing, roaring rush of class IV whitewater; the flesh-freezing harshness of Antarctica in winter. Or the echoing silence and lightless void of Montana’s deep limestone caves.

Mention caving—don’t call it spelunking—and many folks will flatly state, “I could never do that, I’m claustrophobic.” True, caving can involve squeezing through tight passages and squirming along with tons of rock suspended over your fragile body. It can mean hours underground in a chilled, pitch-black hole, battling mud and scraping over sharp rock. Caving can mean darkness so complete your mind has to make up shapes to see; bottomless pits yawning before your trembling toes; twists and turns and multiple passageways so convoluted and confusing you may never see daylight again; cloying mud that sticks to everything it touches; and yes, hibernating bats.

But as the members of the Northern Rocky Mountains Grotto—a Montana group aimed at raising caving’s profile—know, caving also can offer incredible adventures, teamwork and friendship in a hostile environment, skills-building, challenge, and even a chance to go where no human has ever gone before. Cavers get to see geological treasures such as stalactites, stalacmites, flowstone, gypsum crystals, cave bacon, and travertine columns. Montana cavers have even reached the bottom of the deepest limestone cave in the U.S.

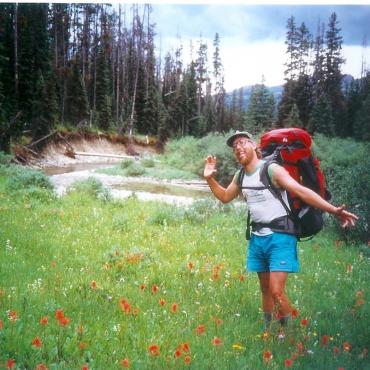

Montana’s vast reefs of limestone, laid down in ancient inland seas from the shells of marine organisms, offer almost limitless opportunity for cave exploration, and locals are pushing deeper and deeper into remote Montana cave systems. (The Bob Marshall Wilderness in northern Montana is the epicenter of extreme Montana caving.)

Montana has over 350 known caves of all levels of difficulty, some of them right in our back yard. Lewis & Clark Caverns State Park offers guided tours of a spectacular, well-lit cave, while Lost Creek Siphon in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness requires rappelling down vertical waterfalls with names like Hurricane Falls. A bit further afield, Bighorn Cave (over 16 miles long) in southeastern Montana requires permission from the BLM for access, and the Pryor Mountains ice caves are beautiful, but gated and locked.

Now, you may not think of holes in rocks as fragile, but the cave environment is, indeed. Caves are not sterile environments. Amphipods, wood lice, sightless insects, and, of course, bats all make use of caves. Bears, mountain lions, mountain goats, and even wolverines use them for shelter. Most caves have been protected from the outside world for millennia, making them susceptible to damage from human passage and changes in humidity and temperature.

The NRM Grotto’s top priority is conservation. Across the U.S., caves have been closed and gated on public land due to vandalism, graffiti, littering, and over-use. Some species of bats hibernate in caves, often in large colonies, and are ecologically important for their role as insect eaters. But a disease called white-nose syndrome (WNS), discovered in 2006, has killed over six million bats in the U.S., and has recently been discovered in Washington state (though not yet in Montana). Cavers are suspected of spreading WNS unintentionally, so caves with bat colonies are typically closed to cavers in areas with WNS. NRM Grotto hopes to conserve bat colonies while also keeping Montana caves open to exploration.

If you’re interested and want something extreme, Montana’s got that in spades. Close to Bozeman, cavers recently explored what they thought was an untouched cave in the Gallatin Range. Upon rappelling into it, they discovered a rusty old tobacco tin with a note dated September 7, 1920 with the names of four explorers who called the cave The Devil’s Watch Pocket. The cave itself was only about 75 feet deep, but the floor was covered in mountain-goat droppings.

My own caving experience, outside of commercial caves like Mammoth Cave and Lewis & Clark Caverns, has thus far been limited to Mill Creek Crystal Cave in the Absarokas. Entering the cave is easy (other than the seven-mile approach), but it quickly gets real. According to NRM caver James Cummins, who has mapped the cave to over two miles in length, getting to the inner cave requires a 300-foot crawl, making it the most remote place he has been. “Rescue from the inner cave would be nearly impossible,” he says. Good thing I didn’t know that when I made that crawl myself.

If you do go caving, be smart about it. Research the proper gear and techniques and tell someone where you’re going and when you’ll be back. Better yet, sign up for a caving trip with the Northern Rocky Mountains Grotto (nrmg.org) and get expert instruction. Then get ready to go deep!