Ankle Biters

It was a clear December afternoon when Linda took Daisy for a walk on a familiar trail. Daisy was sniffing around—off trail but within sight—when she leapt into the air, yelping, thrashing, and biting her front leg. It took Linda a moment to recognize the metal clamped around Daisy’s lower leg, and another moment to recover from the sight of bloodstained snow. She clawed at the trap with her gloved hands, but couldn’t manipulate the levers and release the jaws. The ground was too frozen to dig out the anchor, so Linda placed a panicked call to her vet, who rushed to the trail and was able to free Daisy’s leg. Daisy had shattered several teeth trying to bite through the metal, but was lucky enough to escape without broken bones.

Tales like these are used to demonize trapping and create ever-stricter regulations around the sport. Trapping is a time-honored tradition that clashes with recreationalists as winter trail-use rises, and ground-set traps are unnervingly close to public trails. Even with increased setback distances and well-behaved dogs, romping canines don’t always stick to the groomed path.

On state or federal land, ground-set traps can be legally set 50 feet from trails, nonlethal traps can be 300 feet from trailheads, and lethal snares are permitted at 1,000 feet from trailheads—distances a dog can cover in less than a minute.

Coil-spring leg-hold traps are the most commonly encountered types. While these traps are designed to keep the animal alive—giving the owner time to get help or free the leg—the trauma increases the longer the dog is trapped. Body-gripping varieties like conibear traps are engineered to kill—snapping shut around the neck or torso with as much as 90 pounds of pressure.

This past summer, Montana FWP increased the trap setback distance to 500 feet on 20 high-use areas around southwest Montana. This includes trails in Hyalite Canyon, Gallatin Canyon, and Paradise Valley—a change supported by the Montana Trappers Association. This is a huge leap towards safer trail use; until 2005, traps on public land could be placed 30 feet from trails.

While 50 trapped dogs per year is a fraction of the 40,000-plus traps set in Montana, the trauma and injury to the ensnared pets is enough for trappers and recreationalists to work together to increase safety measures. No trapper wants to find a non-target catch in their trap, but the potential is there and it’s up to all parties to be aware, responsible, and keep multi-use areas as safe as possible.

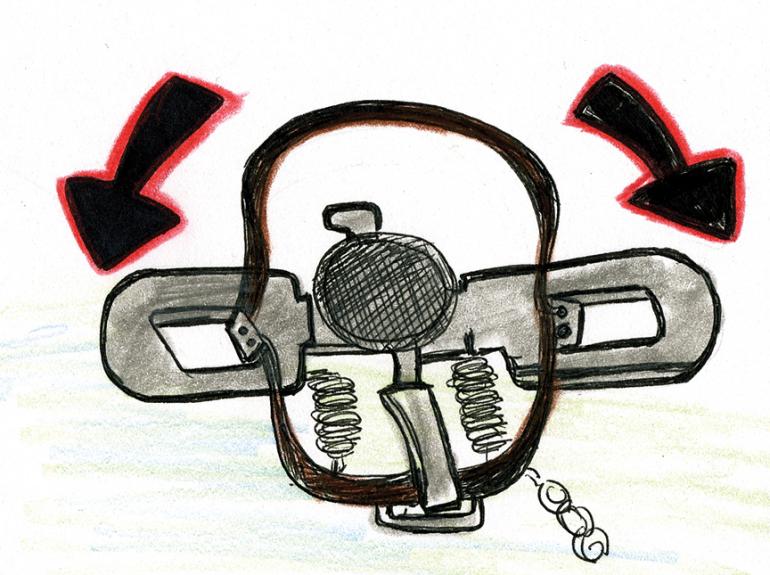

Foothold-Trap Removal:

Your hike took a turn for the worse when your dog stepped on a foothold trap. Remain calm—these traps are not immediately life-threatening, and there are steps you can take to free him:

-Keep your dog as immobile as possible.

-Grab the levers on the sides of the trap with your fingers, stabilizing the base with your palms.

-Pull the levers towards you, releasing pressure on the trap jaws and allowing your dog to pull his foot out.

-If the trap is too large for your hands, place both feet on the levers, pivot forward, and use your bodyweight to release the jaws.

-If you’re unable to open the trap, it’s possible to dig it out from the chained anchor point and carry your dog to the trailhead. If the trap is too difficult to remove, it might be necessary to leave the site and seek assistance.

Trap Avoidance:

The safest way to enjoy the woods during trapping season is to stick to the trail and keep your dog in sight at all times. Traps can be hidden under fallen leaves or snow, and due to the nature of the activity, they’re nearly impossible to spot until you or your dog is on top of them. Footloose Montana has a map of heavily trapped areas, found at footloosemontana.org.

Avoiding high-risk areas during trapping season is also an option. Beaver, otter, mink, and muskrat seasons run from November 1 to April 15. Fisher, bobcat, and marten seasons run from December 1 to February 15.

More season dates and information can be found at the Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks website.

-Maggie Slepian