The Evolution of Adventure

From first ascents to fastest known times.

Montana adventures have certainly changed over the years. We no longer talk to folks we meet along the way about the Great White Father in the East, nor do we hunt and trap beaver when out in the mountains. Some of us still hunt and fish, but few of us dry the meat and use it to survive on our journeys into the backcountry. Our adventures also do not involve guiding or being guided in a wagon train over the Bozeman Pass, though we might run or bike it.

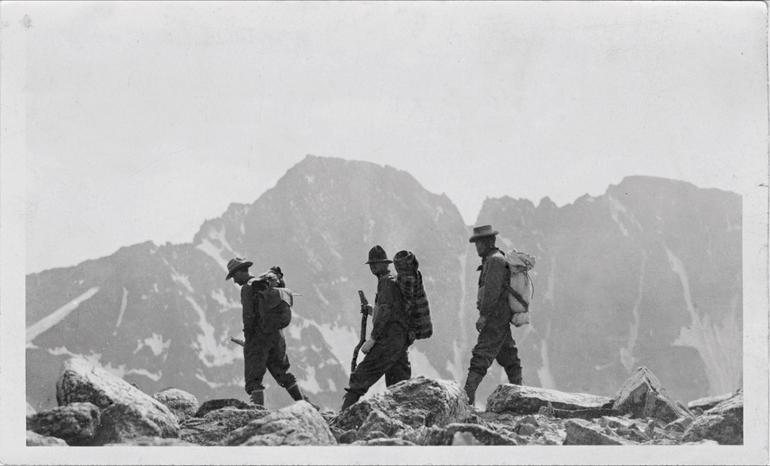

What passes for adventure has changed over the years and continues to evolve. In the early 20th century, there were few roads or trails into the wilderness around Bozeman, and no topo maps. Heading into the backcountry meant riding a horse up or along a creek as far as one could make it, then bushwacking from there on foot. The history of the first attempts on Granite Peak is instructive. Parties had to do reconnaissance to find their way somewhere near Granite, then try their best to figure out which possible route might go. Several organized attempts were made starting in 1889, but the first party didn’t succeed in topping out until August of 1923.

We’d head to local Bozeman outdoor stores and look for the cabinets with large flat drawers that had topo maps laid out in them. We’d buy the maps we needed to piece together trip plans. Distances were not marked on maps and elevation profiles could only be approximated by carefully following topo lines.

Roads were extended into the mountains both for resource extraction and firefighting purposes. In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps built the Beartooth Highway and many of the trails we still use today. Trails, at the time, had value both for recreation and firefighting access.

In the early 1980s, when I started exploring the Montana backcountry, 15-minute USGS maps that showed roads and trails aided in our reconnaissance and made most bushwhacking optional. These maps dated from the 1930s and ’40s. They weren’t perfect, but they were surprisingly accurate. We’d head to local Bozeman outdoor stores and look for the cabinets with large flat drawers that had topo maps laid out in them. We’d buy the maps we needed to piece together trip plans. Distances were not marked on maps and elevation profiles could only be approximated by carefully following topo lines. Maps were green for forested areas, white for rocky areas, and had no gradations in color to emphasize terrain features. One-square-mile dotted squares covered the maps. Trails threaded through these squares and we estimated distances by counting those that the trails bisected. We spent lots of time with a map and compass on high points to make sure we knew where we were, and where we were headed.

There were no guidebooks and no internet sites to provide information in helping us make plans. If something went wrong, there was no heading to a high point for cell service, nor any GPS devices in case of emergency. The backcountry was still virtually empty back then. We’d hike for days and rarely see more than one other party.

Our equipment showed some improvements from earlier eras, but we had nowhere near the variety or quality of what is available today. Our clothing was cotton or wool. The waterproofing for our tents and raingear was vegetable-based, and the odor made you think you’d stunk up your gear, even on the rare occasion that you hadn’t. Our packs had external frames; they squeaked and were heavy. Lightweight stoves were in their infancy; they leaked and often performed poorly. Mostly we counted on building fires to cook each morning and evening. Our food was tastier than a lot of what I eat in the backcountry these days, but it wasn’t dehydrated and it weighed a lot.

Today’s travelers are often better athletes who move faster in the woods. If you are up in the Bridgers in the summer, you might not be faulted for thinking that hiking is “so passe.”

All of this has changed. Today’s gear is better—lighter and with lots of design improvements. We head into the backcountry with a lot more information: maps show distances; some trails have elevation profiles, or summarize elevation gained. We all have mini-computers in our pockets, and satellite phones are becoming a part of our equipment list.

Today’s travelers are often better athletes who move faster in the woods. If you are up in the Bridgers in the summer, you might not be faulted for thinking that hiking is “so passe.” Most everyone up there is running. Fastest Known Times for impossibly hard routes are now in vogue. For Granite Peak, which took multiple attempts by parties over a 34-year period to finally ascend, the record is 5 hours, 24 minutes, 54 seconds, car-to-car, starting from and finishing at the Mystic Lake trailhead—yes, climbs get timed down to the second.

We’ve come a long way from the days of Lewis & Clark and John Bozeman. It’s human nature to push beyond the accomplishments of those who came before. I expect we will see modes of adventuring continue to proliferate, and more adventurers will seek to make their marks by pushing themselves to do what to most of us seem like outrageous stunts. We will also see the crowds continue to build in the backcountry as more people want to see what wilderness is, to define their adventures. However, you define your own adventures—just get out there and get after it, in your own way, as people have been doing all along.