A Montana First Ascent

Climbing Mount Cowen's Black Spire.

When I first saw it, I became haunted by this dog-toothed rock, jutting up on the west side of the Mount Cowen Massif in Montana’s Absaroka Range. It was a remnant of the ice ages, its steep walls pounded by wind, rain, hail, sun, and ice over eons of time. It looked clean as a hound’s tooth, standing there just inside the west boundary of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness Area.

The spire stands at 10,700 feet and can easily be seen from U.S. Highway 87, 20 miles south of Livingston. I wondered if it had ever been climbed. Surely, it had. A rock spire this striking must have had its challengers. I am not the only one who notices these things.

I began to inquire. The spire stood in a national forest, but the U.S. Geological Service mapmakers had taken no notice of it on their maps. I asked some climbers and found out that the MSU Dirty Sox Climbing Club had made some attempts. So I decided to try.

I mistakenly decided the best time to find a route was in the winter—I thought I could ski over the top of the windfall and rock. John Prange and I started up Strawberry Creek on a cold December morning in 1972, with heavy packs and deteriorating snow conditions. We struggled up through the lodgepole pine, our skis plunging through the crusted snow. Paradise Valley is known for sudden changes in temperature and weather, and we had the bad luck to be in the middle of such a change. We finally gave it up, wet and exhausted, miles from the base of the spire.

Then in the early summer of 1973, I promised myself I would find the base of the spire and try to solo it. I was never a good high-angle rock climber. Looking back on it, I was neither physically nor mentally prepared for such a formidable climb.

I left with a four-day pack. I bashed my way up through the lodgepole pine where at 8,000 feet, the trees thinned to glacial scree and moraine ridges. I pushed on up and the scree changed to piano-sized boulders. The spire loomed over me, its vertical sides discouraging a direct climb. I hoped that the east side would reveal a possible route. I could not keep myself from marveling at its impressive sides, although it drained my confidence with each glance. An uneasy feeling formed in the pit of my stomach.

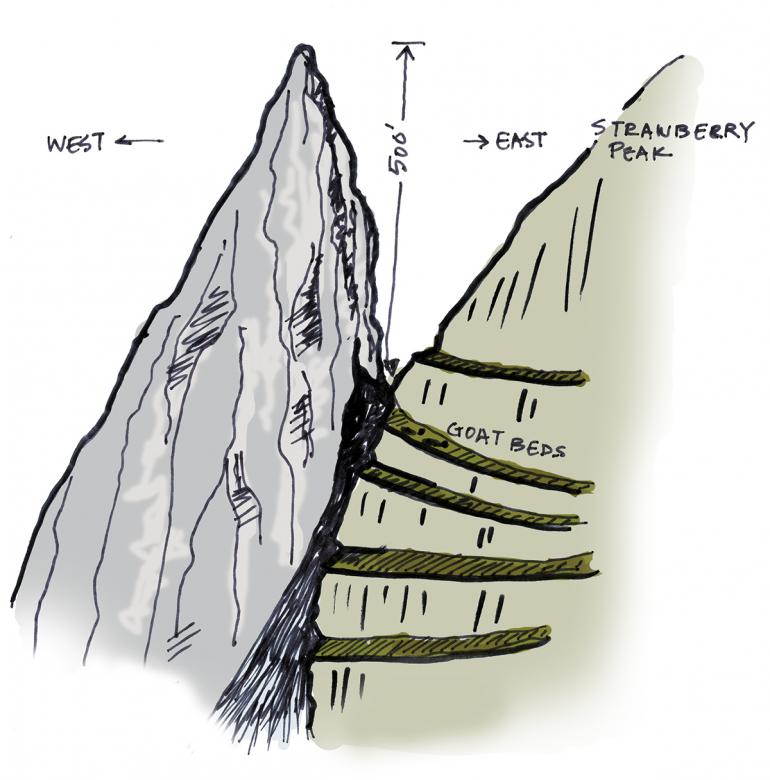

I labored up through the boulders, eventually coming to a series of cliffs and out-sloping ledges that required careful scrambling and climbing. Finally, I hauled up onto the notch that connected the spire to 11,000-foot Strawberry Peak.

The notch was a hundred-foot-long spine, with a narrow top that sloped steeply away on both sides. The north side was a vertical wall, dissected by an incredibly steep ice couloir. To the south, the slope fell away in sheer cliffs and outward-sloping ledges with ball bearing-size gravel, waiting to skid me into a gigantic stair-step fall.

I found two concave beds that had been dug out of the soft material above the cliff by mountain goats. I settled into the larger bed, melted snow over my faithful Primus, and ate a meager supper.

A thunderhead came over the top of 10,154-foot Dexter Point, its dark roll-cloud out in front and rapidly approaching. I knew I was in for a beating. The goat beds were my only security, but I had no protection from the wind. I could move across the notch to the lee side of the spire, but that would increase my exposure to lightning. I stayed where I was with that helpless feeling of being trapped and in for a pounding. I shook out my GI poncho, put my head through the hood hole, sat on the top of my pack and watched Dexter Point rapidly being obscured below me by the thunderhead.

The cloud rolled in, and the rain pounded my thin poncho. Water filled the goat bed. One or two hailstones rifled in, then a torrent started and I wrapped my arms around my head in a feeble attempt at protection. Finally the thundercloud passed, leaving me cold, wet, and shaken. Daylight dimmed and darkness came. I was stuck for the night, with water dripping on me from above. I spent the night sitting on my pack wrapped in my wet bivy sack, and nodding off in fitful snatches of sleep.

Dawn came clear and cold at 5 am. The sun would not shine into my bivouac until 10, and the water was frozen in my black pot. I built a windshield around the stove. The flame caught and I cupped my hands around its fragile warmth as it heated the pot. Breakfast was a mixture of dry cereals and raisins, with powdered milk and hot water poured on top.

Reluctantly, I gave up my wet bed and moved across the narrow spine; the east side of the spire loomed over me. I let out the gold line and rigged for self-belay and self-arrest. I began to move up into the first hand and foot holds. A system of deep cracks and blocks formed this side of the spire. I guessed it would take four or five 100-foot rope leads. Although this was the steepest route, it was the shortest and most protected from the constant wind.

I still had that sick feeling in my stomach and quickly became shaky with fear. I knew I was beaten and belayed back down to the base. I felt relieved of the burden of climbing the spire, but depressed about the amount of effort I had given to failure. The spire seemed to mock my puny efforts.

The spire continued to gnaw at me that year, and in August I convinced my 15-year-old son, Mike, to go back with me. Mike was a good all-around athlete and a top-notch wrestler. If I had a good dependable belay, maybe we could make it to the top. As we left that early Saturday morning, my wife said, “If you kill that boy on this foolishness, jump right on after him… don’t come back here.”

Once again, we lugged heavy packs up through the tangle of lodgepole pine and windfall. Late in the day, we broke out of the forest onto the glacial moraine boulders. The spire loomed over us now, with its impossible walls. We climbed up through the cliffs and hauled out on the goat beds just before dark. After supper, we tucked into our sleeping bags and bivy sacks under a starry black sky with a cold wind coming in over Dexter Point.

Morning followed a worrisome night. I had a slight headache and that feeling back in my stomach. Milly’s words rang in my ears as our only son slept comfortably in his down bag. I woke Mike and started up the stove, warming water from a snow bank. I had decided not to commit Mike to the climb.

Mike was totally disgusted with me. We came all the way up here and were not even going to give the spire a good try. My 15 years of trying to impress him blew away like a stack of cards in the wind. After I made my way across the narrow notch to the base of the spire, I looked at the top of the crack system that stopped me the last time, and knew it had stopped me again.

Over the year, I thought about my three failed attempts. I was also convinced that if I did not do it this year (1974), I would never do it.

First, I had to get someone who knew how to climb high-angle rock, a skill that I lacked. I talked to Don Alford, a geology instructor at MSU and avalanche researcher. Don was not interested, but he gave me a name: Barry Frost, a rock climber recently moved to Bozeman. Barry had been active in Missoula’s Rocky Mountaineers, a club I had helped organize in the mid-1950s.

Barry was a strong-looking young fellow who quickly sensed that I was using him to meet my own goals. He was at the height of his climbing power and was interested, if it really was an unclimbed peak.

We departed on September 28, 1974. I felt quite optimistic. We bashed up through the thick forest, then crawled through the large boulders on a slightly different route to a less-exposed camp. We spent the first night at a sheltered, small lake in the cirque. Barry schooled me in some of the basics of chocks and nuts. We left camp at dawn and climbed up through eight inches of snow.

The spire’s dark summit began to poke up above the ridge. It looked like something from another planet. I glanced at Barry’s face for a reaction. His worried look immediately dimmed my confidence. Barry started to favor a less-steep route on the spire’s west side. I knew any route besides the east-face system would take days to set up, and the weather was already deteriorating.

My hopes began to fall and misgivings mounted. If I could only get Barry on the rock, in the crack system, I knew he would be okay. We discussed the route further and he finally agreed.

We made our way past the goat beds and onto the narrow spine that connects the spire to Strawberry Peak. We tied into our harnesses, I set up a belay, and Barry reached up for the first holds. He climbed steadily, setting chocks and slings within the protection of my belay. The first rope lead ended ten feet below where I had stopped on my first solo attempt the year before. I moved up to the stance, tied into the sling, and set up the second belay for the next rope lead. Barry continued leading past this difficult place while setting chock protection in the cracks of the rock.

The crack system we were climbing disappeared in an overhang. We were now faced with the problem of getting over to the left side. The only way was a hand-over-hand traverse to the left, with only friction foot holds. This required technique, which was difficult for me.

We were three rope leads into the climb with 300 hundred feet of exposure to the notch below. This was the crux of the climb. We set up a belay point sling, and Barry began the precarious hand-over-hand crossing to the left. With white knuckles, I carefully fed out the rope to him, keeping the slack to a minimum in case of a fall. Barry seemed to take a long time to make the crossing, and I sweated out each of his moves. He made it, moved into the left side of the crack system, and climbed 30 feet higher before setting belay. I gingerly made my way across and congratulated myself when I arrived on the left side.

It appeared that two more rope leads would lead us to the base of the top rock. This required about one and a half hours of careful climbing and belaying, when finally, Barry pulled me up onto the cap rock with nothing but sky and clouds above us. The two of us could barely fit on the narrow top. The wind pummeled us and threatened to blow us off the top. We hurriedly filled out a register, put it into a plastic tube, and tucked it into a crack under the cap rock.

I was elated. We had accomplished what I thought was an impossible task for me. We thought perhaps it was a first ascent. Now, if we could only get down out of this cold wind.

Barry set up the first of five rappels. Off I went. When we let down past the hand-over-hand traverse that had almost stopped us on our climb a few hours earlier, I thought about the thin thread between success and failure. We picked our way across the ridge, and I looked back at the spire and silently gave thanks to the mountain and the weather for allowing us this climb. My confidence in Barry’s skill and his faith in my knowledge of the mountain had resulted in success.

Gary Tuckner and Bill Favre of Livingston made a second ascent on June 26, 1977. They found our register. On October 8, 1984, my good friends Rick Reese and Bill Long climbed the spire and said, “The only names on the register were Frost and Gutkoski, and Tuckner and Favre.” Perhaps it was a first ascent after all.

Joe Gutkoski was an avid hunter, fisherman, canoeist, climber and conservationist. He passed away in August 2021.