Raiding the Hive

A karmic encounter in the Spanish Peaks.

On a sunny morning in mid-August, we packed small backpacks and drove up the canyon to Beehive Basin. The broad south face of Beehive Peak had always enticed me as a mini alpine-climbing objective close to home, and I thought we’d try its most difficult, but reputably most quality, route: Java Man, a five-pitch crack climb with moves up to 5.10. A far cry from the towering spires of the Cowen Cirque, but “alpine” nonetheless, and much easier to access.

Our pace on the trail was just shy of a jog. The pitches were said to be short, so we took a light rack. A skinny single rope would suffice, as there’d be no rappels—provided we made it to the top. We carried no water, since we knew there’d be sources near the climb. For food, just a PB&J tortilla each. Thankfully, none of these cut corners did us in.

Still, alpine climbing usually entails unforeseen circumstances. And in late summer, those circumstances often arrive in the form of an electrical storm. It’s not a matter of if, but when, and on that day, when was at the top of the first pitch.

We raced to the top and enjoyed breathtaking views from the summit, as beams of sunlight shone through cumulonimbus clouds over the Spanish Peaks and spilled across onto Lone Peak.

The storm wasn’t on top of us yet, but we could see it building to the south over Wilson Peak. Dark grey clouds blocked out the sun, but overhead was still blue sky. The first pitch, rated 5.9, had gone a bit harder than expected. The rock was warm from the recent sun and our hands were sweating. The cracks didn’t cut straight in, but rather sliced back and forth at awkward angles, making it tedious to find secure jams.

Nonetheless, I felt we had plenty of time to get up and off. Meanwhile, I noticed something peculiar: above our belay, two shiny Camalots equalized by a sling were affixed in the crack. I immediately knew that someone had recently bailed, but I wondered why. Caught in a storm? Injured? Too difficult? Whatever the reason, we were going up.

The next pitch—the crux—featured more booty. Along the way, slings hung down from several nuts that were easy to remove, and halfway up the pitch was the final ornament: a third shiny cam. What luck! We were harvesting a couple hundred bucks worth of climbing gear.

Then the real difficulty arrived. An easy layback corner sealed shut and demanded some engaging slab climbing far above the last protection. Once the crack opened up again, the corner steepened to past-vertical and the hardest moves were before me. Gear was available, but the climbing was steep and awkward. I tried slamming my hands into the too-small crack, scraping my skin on the rough stone. I looked above. Tendrils of cloud spiraled directly overhead. There was no time to burn. I swallowed my pride, pulled up on some cams, and built a belay.

My partner arrived, also with difficulty, and wasn’t enthused. We were both growing wary of the impending storm. But the crux was behind us, and with easier climbing on the next three pitches, it might have taken nearly as long to go down than up. Plus, we’d be abandoning our newfound spoils in the process.

Eventually, I decided to make at least the minimal effort in returning the gear.

We raced to the top and enjoyed breathtaking views from the summit, as beams of sunlight shone through cumulonimbus clouds over the Spanish Peaks and spilled across onto Lone Peak. After snapping a few photos, we were off, scrambling down the snowless, rubble-ridden Fourth of July Couloir as raindrops began to patter upon our helmets. When we reached the base of the gully we knew we were probably safe, and not long after, the first bolt of lightning cracked merely half a mile away from where we’d been standing 30 minutes before. Talk about threading the needle.

We donned our rain shells—a necessary provision in late summer—and plodded back to the car. At home, I unpacked my bag and proudly hung those three extra cams along with the rest of my rack. A day well spent.

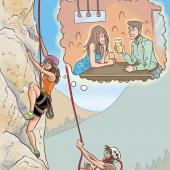

But something wasn’t sitting right. Though I’ve had closer calls in the mountains, this had not necessarily been an easy escape. And while I don’t often pander to superstition, the cosmic balance felt a little out of whack. I didn’t need this gear. I already had plenty of cams, and everyone I climb with has plenty, too. I sat on it for a few weeks, debating with myself over who was the rightful owner. Eventually, I decided to make at least the minimal effort in returning the gear.

I posted in the local climbing Facebook group and within a few hours, the exact missing pieces were correctly identified. It was easy to give up my prize; it felt right. I coordinated a time to meet outside my office and a muscly man stepped out onto the sidewalk. He was about ten years older than me, wore nicer clothes, and drove a nicer car.

“Thanks man, I really appreciate it. I got sick up there and forced my partner to bail with me. Here ya go.” From his outstretched hand stuck a crisp $50 bill. I turned it down. “Pay it forward,” I said.

You never know when you might need to bail.