Collective Bargain

We’re all in this together.

“Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much.” —Helen Keller

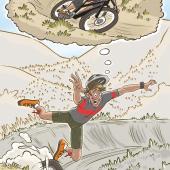

A climber, smiling ear-to-ear as she ambles back to her car. A mountain biker and his dog cautiously negotiating a tight switchback. A turkey hunter bounding downhill, carrying nothing but a loose gait and contented disposition. A trail runner, out for a jog and possibly an overlooked elk shed.

All this, at one trailhead in Bozeman.

A trail runner’s candy wrapper, tumbling in the breeze. Ruts left by a mountain biker, hardening in the sun. Last season’s discarded elk carcass, rotting by a creek. An overplayed trout, belly-up in an eddy. Trails widened by horses, plodding around puddles in early-season mud.

All this, at the same trailhead in Bozeman.

Every year, three and a half million people visit the Custer-Gallatin National Forest, the lion’s share setting out from Bozeman. Our impact is undeniable. We hike, backpack, fish, hunt, bike, camp, ski, paddle, and climb all over the Forest’s almost two million acres, and everywhere we go, every one of us leaves a mark. That is not up for debate.

What is often debated—or rather screamed silently across the void of the internet—is who makes more of an impact than whom. Who should we keep out so that others may be let in? What needs to be restricted and what should be expanded?

This approach serves only to weaken what would otherwise be an unstoppable force for conservation of our public-lands resources. Together, we’re millions strong with mostly common interests. Divided, we’re ineffectual and self-interested, establishing hierarchies of access that put the existence of public lands and the landscapes we cherish at risk.

While it’s hard to find examples of collaboration, they do exist. Take the horsemen, mountain bikers, and federal-land managers partnering to clear trails in the Lionhead area outside West Yellowstone (p. 42). Or the private landscapes across southwest Montana being conserved by nonprofit entities for the good of sportsmen and wildlife alike (p. 64). Or the ranchers, fishermen, private landowners, and fisheries biologists developing water-management solutions in the Jefferson Valley so that a formerly proud river may once again thrive (p. 98).

As officials from the Custer-Gallatin work through the Forest Plan Revision, these collaborative efforts should be celebrated and held up as examples of what a community is capable of when it’s willing to work together. The Gallatin Forest Partnership is another example of this spirit. This collection of conservation groups, recreation advocates, business owners, and concerned citizens has put differences aside and focused on long-term sustainable solutions to public-lands management that will empower instead of embitter; it builds instead of divides; and acts instead of reacts. This is the approach we must take for a durable management outcome.

It’s difficult to accept that we harm the things we love, but self-awareness and accountability are essential if we wish to continue enjoying public land, no matter how we enjoy public land. This means stopping on a trail to drain a puddle. It means taking five minutes to write a letter to the Forest Service when given the opportunity. It means volunteering for trail work or habitat restoration. It means accepting that we all have an impact. And it means understanding that we have more in common than we realize.

At that Bozeman trailhead, every user is happy. They all pursue pastimes of their choosing, doing so without intentionally affecting one another’s day outside—their means different, ends the same. Remember that as you run, bike, hike, camp, fish, paddle, and climb this summer. Consider your presence and act accordingly.

We’re all out there together.