Mutual Fund

As our outdoor economy booms, it's time for all of us to make a shared investment.

Montana is a treasure trove of outdoor recreation, a vital and growing sector of our state’s economy. An estimated 81% of residents participate in outdoor recreation each year, spending $7.1 billion annually while creating 71,000 direct jobs in 2017.

Public land is the key component of the surrounding communities and part of their competitive profile. With mobile technology untethering society, businesses can choose to locate wherever they wish, and towns like Bozeman prove that outdoor recreation attracts new business and sustains jobs.

Getting outdoors is also good for our mental and physical health. In 1865 Frederick Law Olmsted, an American landscape architect most famous for designing New York City’s Central Park, observed that “it is a scientific fact that the occasional contemplation of natural scenes of an impressive character… is favorable to the health and vigor of men and especially to the health and vigor of their intellect.” Today, a growing body of research documents how spending active time outdoors secures a wealth of benefits, from increasing our immune response and reducing near-sightedness to improving short-term memory and reducing depression and obesity.

One last benefit is more philosophical and existential. Can those of us who care about wild things in wild places expect subsequent generations to be champions for natural-resource conservation if they don’t have a personal connection with the outdoors? One cannot have the “occasional contemplation of natural scenes of an impressive character” via mobile phone or Instagram. For the next generations to be conservation advocates, they need a physical, first-hand connection to the outdoors.

At TEDx Bozeman last year, I asked the audience the following question: “More people are doing it; it’s good for the economy; it’s good for our health; who’s paying for it?”

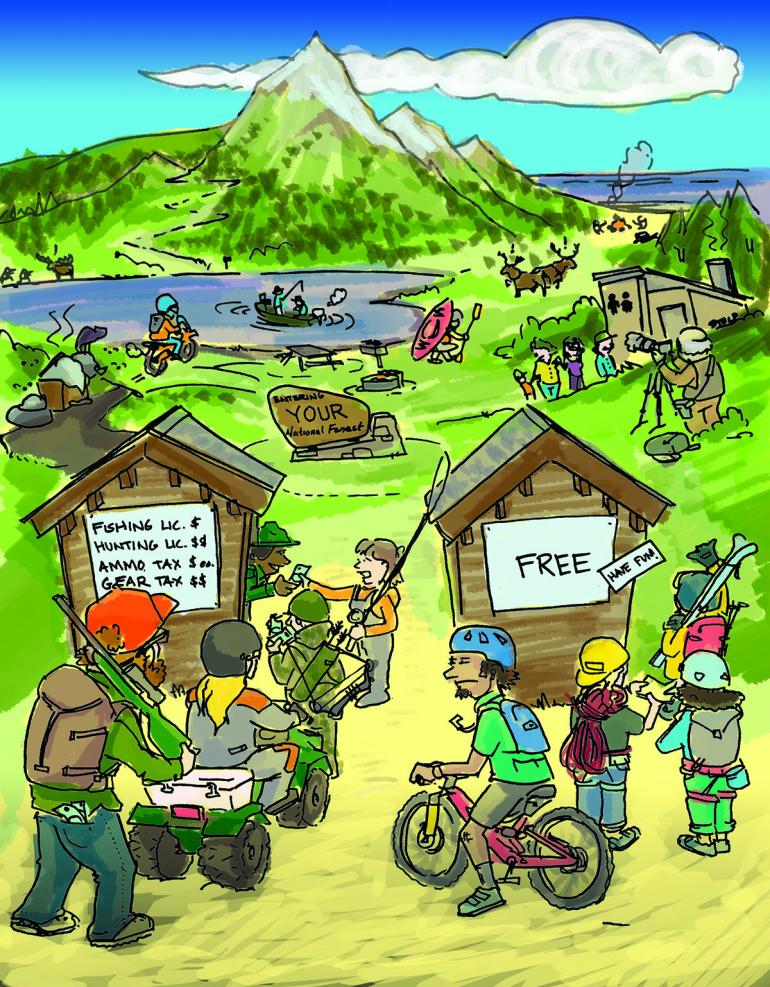

As I have explored and discussed the question of “who” with colleagues and friends, I have discovered an overly hopeful view of how management of our public lands is funded. To the question of “who pays for our outdoor recreation in Montana,” I would respond that hunters and anglers pay their way. Those of us who recreate in other ways on public lands could do better.

But We Pay Taxes!

It is logical to conclude that we pay our federal taxes, we recreate on federal public lands, therefore we must be helping pay our share for our public-land recreation. Logical, but incorrect.

Former Treasury Under Secretary Peter Fisher observed that the federal government functions as “a giant insurance company with a side business in defense and homeland security.” The federal government spent nearly four trillion dollars in 2016. To comprehend that mind-boggling number, imagine a stack of $1 bills rising some 270,000 miles, from Earth to beyond the moon. After Uncle Sam pays 73% for payments to individuals (e.g., Social Security, Medicare), 15% for defense, and 6% to service the national debt, everything else, from highways to foreign aid, research to national parks, adds up to less than 6% of our tax dollar. And public-lands management is a pittance of that meager slice.

If we examine the budget of the U.S. Forest Service, arguably the largest purveyor of outdoor recreation, the trend is all too obvious. For the period 2012 to 2016, the Forest Service’s overall discretionary appropriation remained largely unchanged. But funding for wildland-fire management buoyed the budget, consuming (no pun intended) a larger and larger portion. If we examine funding trends for actual program activities, the picture is grim. For 2001-2015, recreation and wilderness funding was down 15%, wildlife and fisheries 18%, facilities 68%, and deferred maintenance 95%. Yes, we pay taxes—but increasingly not to support the outdoors.

Moving closer to home where Montanans enjoy over 30 million acres of state and federal lands, it might be logical to conclude that our state taxes pay a share for our public land recreation. Again, logical but incorrect.

Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks (FWP) is the state agency responsible for managing the state’s fish, wildlife, and habitat resources, including 55 state parks, 68 wildlife-management areas, and over 300 fishing-access sites. The agency’s budget is nearly 100% paid for by hunters and anglers. Seventy five percent of FWP’s FY 2017 revenue came from hunting and fishing licenses and other fees, including an auto-registration fee committed to state parks, and 24% from the excise tax paid on selected hunting and fishing gear. General fund dollars, our tax dollars, provide little to none of FWP’s annual budget. At present, FWP struggles to meet its mandate with a limited budget.

Rights, Privilege, and Pay to Play

Americans have unrivaled opportunities to hike, hunt, fish, and camp on millions of acres of public land. In total, more than one-third of the nation is in state or federal ownership, managed in trust for the American people, and open to many recreational uses. As American citizens, we have the right of access. This right is the result of a complex history of land settlement, states’ rights, and managing for multiple uses. The 1800s and early 1900s saw largely unfettered access to public lands. The resulting damage to forest, range, and water resources taught hard lessons of the need for our right of access to be tempered by the privilege of access. For example, waterfowl and wetlands were devastated by the early 1900s—too many hunters with too little sense of responsibility coupled with industrial growth and no regulation. Fortunately, citizens like George Bird Grinnell and Theodore Roosevelt, along with organizations like the Audubon Societies and Boone and Crocket Club, fulminated for the passage of game laws and land-use regulations that preserved the right of access conditional on the privilege of access. So if hunters wanted to continue to hunt, they had a responsibility to help fund the management and conservation of fish and wildlife. Buying a license, gaining necessary permissions, and obeying game laws gave them the privilege to hunt. Abuse the right and you lose the privilege.

Hunting and fishing are arguably society’s oldest recreational pursuits. They are direct descendants of the need to put food on the table, and numerous subsistence and commercial forms of hunting and fishing continue today. Today’s ability to hunt and fish recreationally is the result of a longstanding relationship between the states responsible for managing the resource and the users. Over time, hunters and anglers imposed levies upon themselves, recognizing a shared responsibility to ensure the future management of fish and wildlife, if they and their children were to continue to enjoy it.

One example is the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program. Beginning in 1937, a series of Congressional actions created a “user pays, user benefits” program where hunters, anglers, boaters, and others pay an excise taxes on their purchase of guns, ammunition, fishing equipment, boat fuel, and similar items. In 2017, these excise taxes returned $1.13 billion to state and territory fish and wildlife agencies for wildlife habitat projects, river access, aquatic education, and more, including $29 million to Montana.

Myth of the Non-Consumptive User

The tradition of hunting and angling goes hand-in-hand with the responsibility of giving something back. Hunters and anglers are declining as market share, but people are recreating in the outdoors as never before. Roughly half of all Americans participate in some form of outdoor recreation, which continues to grow both in total numbers and the range of activities. Unfortunately, too many recreationists have too little appreciation for how public lands are funded, assuming their tax dollars help fund their play or that their preferred form of recreation doesn’t cost anything to provide. This latter thinking leads to the “myth of the non-consumptive user.”

A common reaction to my concern about “who pays” is the sense that hunters and anglers are shooting and hooking creatures, so it’s appropriate that they pay license and access fees. Other forms of recreation, like trail running, mountain biking, and backcountry skiing, do not consume the resource and are therefore benign. Reality presents an alternate view, however. As an increasing number of researchers are documenting, so-called non-consumptive users occupy a larger and larger physical land mass just by sheer numbers alone. They demand spatial separation (the “wilderness experience”), erode trails, and trample vegetation. Even the quietest hikers actively displace wildlife. Trash removal, sanitation facilities, and trailhead information kiosks are taken for granted. Rafters and kayakers enjoy access sites paid for by anglers. Perhaps worst of all, the myth of the non-consumptive users lulls us into believing one use is more righteous than another. Instead of viewing all outdoor recreationists as fellow travelers, we defend our own use, often by calling for the curtailment of other uses.

A Path Forward

The issue at hand is that our growing participation in outdoor activities comes with little or no corresponding commitment to help pay for the added costs. Meanwhile, the state and federal agencies expected to provide these recreational opportunities face tighter and tighter budgets and smaller and smaller staffs. I suggest two courses of action that offer promise.

We pay homage in the form of taxes to Washington D.C. and Helena. The Outdoor Industry Association reports that the nation’s outdoor recreation economy generates $65.3 billion in federal tax revenue annually and $59.2 billion in state and local tax revenues. But the outdoors continues to lose its already pitiful share.

Count me gobsmacked, but we make it easy for our elected representatives to ignore us. We speak not as a single voice but as a cacophony of conflicting, shouted demands. Each group begs for its table scrap—expanded access here, no logging there, stop offshore drilling but fully fund the Land and Water Conservation Fund. All the while our collective plate gets smaller.

In 1849, a distressed Henry David Thoreau, witnessing the migration of salmon and shad blocked by dams, asked “who hears the fishes when they cry?” Today, Congress and the Montana Legislature need to hear the cry, “Where’s our return on investment?” It is past time for all organizations professing an interest in public lands to jointly lobby for baseline funding for the Forest Service, Montana FWP, and their kin. Speak as one voice for the baseline funding, then each group can lobby for its additional prizes.

The second path is to raise new funds. Expanding the excise-tax model of hunting and fishing is one avenue. There are numerous statewide revenue examples, from Colorado’s Great Outdoors lottery to Missouri dedicating a 1/8-cent portion of its sales tax to its conservation department. In the private sector, there are countless examples where businesses, conservation groups, and individuals have made major contributions to funding recreation projects, ranging from the purchase of large tracts of land to local bike clubs and backcountry horsemen conducting routine trail maintenance. Private investors have stepped forward to provide upfront capital for construction of new trail systems—their return on investment being a percentage of the resulting increase in economic activity. All of these efforts are conducted in partnership with state and/or federal land-management partners. Collectively these efforts are vital and must be continued and expanded.

It’s time to build a true constituency for public lands. Instead of arguing among ourselves about whose use is most holy, it’s time to demand an adequate investment in the sustained and proactive management of our public lands, for wildlife, wilderness, clean water, and recreation. Time to put our voice and money where our footprints are.