The Long and Winding Road

Strain, struggle, and (eventual) solutions on southwest Montana's most notorious highway.

As he drove home along the narrow, winding road from Big Sky, Corey Hockett consciously lowered his speed in anticipation of the patches of black ice hiding in the shady stretches of Gallatin Canyon. Hockett knew the road well. He’d been commuting from Bozeman to Big Sky for years, and he grew up here, learning to drive on slick winter roads. He knew when potholes could be avoided and when hitting them head-on was the best—and only—option. He knew to expect wildlife crossing on the canyon’s blind corners, and that construction and standstill traffic were a common occurrence throughout the entirety of the two-lane roadway. As a seasoned commuter, Hockett understood how to safely navigate the canyon—but there was one obstacle he couldn’t predict.

“All of the sudden, I see this car coming directly toward me,” Hockett remembers. The oncoming driver—later revealed as a distracted tourist who had just flown into Bozeman and was traveling to Big Sky—hadn’t noticed the standstill traffic in his lane up ahead. In a panicked effort to avoid rear-ending the vehicle in front of him, the driver swerved directly into Hockett’s lane, causing him to “flip a 180 into a ditch,” rolling his truck and totaling it. “We almost killed each other,” Hockett says. “If it had been a snowplow or a semi, that would’ve been it.”

Three months after Hockett’s collision, the driver of a Toyota Tacoma failed to navigate a curve on the same stretch of road, causing her to drift into an oncoming ambulance. The collision sent the Tacoma off the roadway, overturning it and claiming the driver’s life.

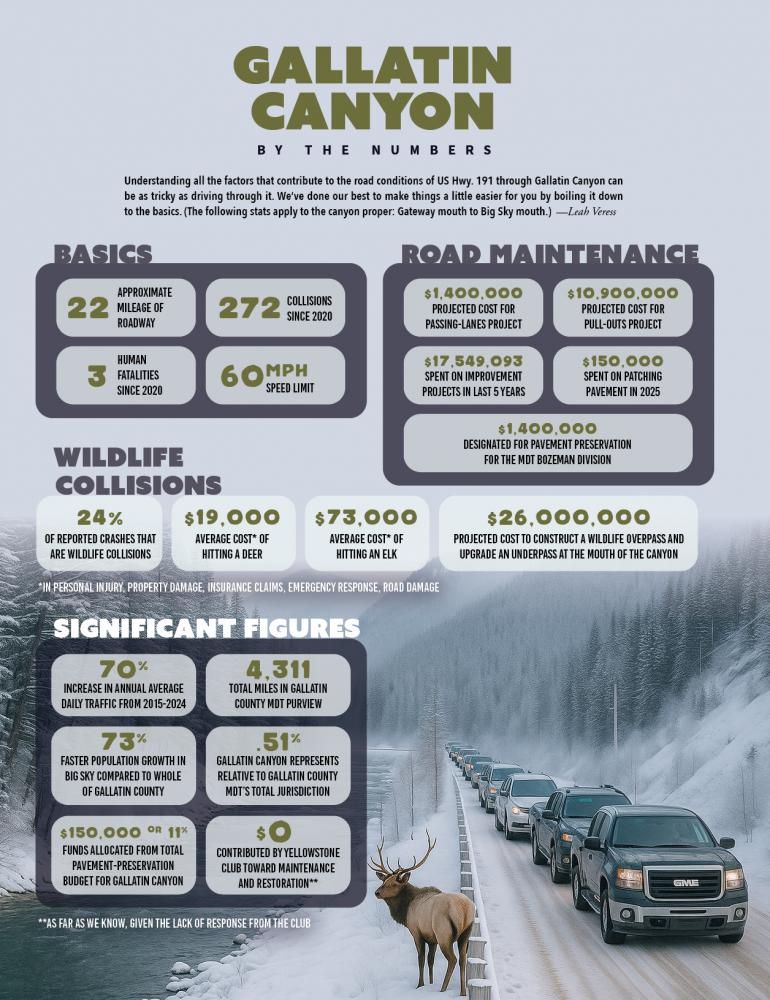

Montana Highway Patrol has responded to 263 crashes in Gallatin Canyon since January 1, 2020. Of these, three have resulted in fatalities.

Montana Highway Patrol (MHP) has responded to 263 crashes in Gallatin Canyon—from milepost 63, at the northern mouth of the canyon, to milepost 48, at the Big Sky stoplight (a.k.a., MT Hwy. 64)—since January 1, 2020. Of these, three have resulted in fatalities.

Dispersed between signs alerting drivers of icy road conditions, upcoming pull-outs, and trailheads are dozens of white crosses, each mounted on red posts and adorned with American flags. Some are erected in tandem, trios, or even quads—each one symbolizing a life lost on the roadway. They not only commemorate the departed but serve as a reminder to drive safely.

“Protect yourself by driving defensively,” says Captain Doug Samuelson, commander of the Bozeman Division of MHP. “Slow down when necessary, and don’t drive impaired or without a seatbelt. The best advice I can give winter drivers is to give yourself plenty of time—oftentimes, road conditions change quickly and an accident can block things up for hours.”

What’s Goin’ On?

For Hockett, slowing down in anticipation of ice and slow-moving traffic was second-nature, but for many motorists traveling through Gallatin Canyon, both mountain and winter driving are unfamiliar. “I moved here from Vermont—we have cold, icy winters there too,” says Will Lewis, a ski instructor who commutes from Bozeman to Big Sky. “But Montana roads are slicker, because they use sand instead of salt. The canyon is especially bad. It’s tight and curvy; you really can’t drive the posted speed, and a lot of people’s rigs just aren’t equipped for it.”

Hockett and Lewis are a part of the 58% of Big Sky’s workforce that commutes from other municipalities. Since Hwy. 191 is the only public roadway connecting Four Corners to West Yellowstone, most commuters living north of Big Sky utilize the roadway almost daily. “It’s one of the worst commutes in the state,” Hockett points out. “As far as traffic density, wildlife crossings, overall road conditions… there’s no question—it’s one of the worst roads to drive, year-round.”

He’s not the only one sounding the alarm. Concerns about the canyon come from every corner of the community—longtime commuters, seasonal workers, tourists, and businesses alike. “Our office has become the ‘collector of complaints’,” says Brad Niva, director of the Big Sky Chamber of Commerce. “They tell us about rockslides, missing paint lines, potholes.”

“I’ve had so many co-workers and friends blow tires going through the canyon, that I avoid Bozeman like the plague now.” —Big Sky resident

Without a municipal government, the Big Sky Chamber has become the middleman between motorists and the Montana Department of Transportation (MDT), the organization responsible for maintaining the highway. Over the last few years, Niva says the Chamber has made it a top priority to help MDT identify problem areas and notify motorists of scheduled construction. “No one likes surprises,” she says. “If we can tell people, ‘Hey, new guardrails are going up next Tuesday,’ it helps them plan and reduces frustration.”

Niva also notes the improved communication since Bozeman Maintenance Chief, Josh Ritchie, came on. “We handle pretty much anything that happens on the road,” Ritchie says. “We pick up wildlife that’s been killed, mow in the summers, do culvert-cleaning, panel rockslides, move materials, put up delineators & signs, repair cable rails, guardrails, and fill cracks & potholes.”

Ritchie’s crew consists of approximately 60 full-time employees, and his department, the Bozeman division, is responsible for 4,311 roadway miles. Gallatin Canyon, spanning approximately 22 roadway miles, represents just 0.51% of the territory Ritchie’s team is responsible for maintaining.

With an annual pavement-preservation budget of $1.4 million—derived from the Montana State fuel tax—the stretch of Hwy. 191 that winds through Gallatin Canyon receives a disproportionate percentage of maintenance funds. This past year, Ritchie says that the canyon alone required $150,000 in patching—nearly 11% of the annual budget for just 0.35% of the roadway.

But despite the maintenance efforts made by Ritchie and his team, the highway remains riddled with hazards and the complaints keep piling up. “I started getting my groceries delivered, the road is so bad,” one Big Sky resident says. “I’ve had so many co-workers and friends blow tires going through the canyon, that I avoid Bozeman like the plague now.”

While the focus of complaints vary, the majority of them hinge on congestion, road degradation, and vast deviations from the 60mph speed limit.

Neither the broader passing-lane package nor the pull-out project made it into MDT’s five-year plan, meaning motorists likely won’t see construction for several years.

Road Conditions

At any given time, a motorist traveling north- or southbound through Gallatin Canyon will encounter a myriad of hazards: potholes, cracks in the road, and stretches of roadway without painted center lines.

Brandon Jones, a preconstruction engineer with MDT, explains that while some of the road degradation is caused by weather—notably the characteristic freeze & thaw patterns prevalent during long Montana winters—most of the wear & tear the roadway takes is inflicted by a steep incline in traffic frequency. “The area is exploding,” confirms Niva. “Between development in Big Sky, growing populations throughout Gallatin County, and the number of commuters, the road takes a beating.”

An MDT traffic count site positioned just north of the intersection of Hwy. 191 and the northern mouth of the canyon shows a nearly 70% influx in annual average daily traffic (AADT) from 2015 to 2024. Similarly, a site positioned 1.5 miles south of Gallatin Gateway reveals a 55% increase over that same period.

Big Sky’s population doubled from 2010 to 2020, growing 73% faster than the rest of Gallatin County. Major resort expansions—including the Yellowstone Club (YC), Moonlight Basin, and Spanish Peaks—as well as the Big Sky 2025 plan, which added lifts, employee housing, parking, and snowmaking capacity to Big Sky Resort, have fueled a surge in commuter and heavy-construction traffic alike. With Hwy. 191 serving as the primary route for workers, visitors, and equipment, the canyon now carries the full weight of the region’s rapid growth.

“I see a lot of huge trucks heading to the Yellowstone Club,” says Lewis, who drives the canyon daily for work. “They’re loaded with boulders or are full of gravel and topsoil. All that weight wears down the road fast, and we end up with frequent, half-baked fixes.”

“There are way more semis traveling 191 these days. But everyone knows where those construction trucks are going.” —Longtime Big Sky commuter

To address the issue, MDT is developing proposals for new weigh stations along Hwy. 191 and plans to activate an existing station south of Four Corners. Overweight trucks would be fined, though Jones says those funds won’t go directly toward canyon maintenance. The project remains in early planning, and construction is likely years out.

Some commuters have called on wealthy entities, like the YC, to help foot the repair bill, arguing that they have played a disproportionate role in the road’s degradation. Outside Bozeman reached out to the Club for comment, but no response was received. Since Hwy. 191 is a federal highway, all of the funds for maintenance and construction currently come from the government, by way of tax dollars.

Jones says that independent parties helping fund maintenance projects is uncommon, but not unheard of. However, he says that pinning the disrepair of a roadway like Hwy. 191 on a single entity is difficult, if not impossible. “We look at different types of vehicles, and we do our traffic counts. But we don’t have a mechanism to know where a truck going south down 191 is headed,” he says. “We can make some guesses, but it’d be difficult to know where their end destination is with confidence.”

But many commuters tell a different story. Says one longtime Big Sky worker, “Sure, there are way more semis traveling 191 these days, what with the growth in Bozeman and Belgrade. But everyone knows where those construction trucks are going. They’re going to the Club, or to one of the other Lone Mountain Land developments.”

Another commuter suggests a mandatory heavy-truck stop at the northern mouth of the canyon. “A simple check station, like FWP does for hunters and aquatic invasive species, would identify each vehicle’s actual destination,” she offers. “Like one of those coffee huts—two windows, two workers, for a couple hours each morning. They could do it for a week, or even a few days, just to get some hard numbers. Why not at least give it a shot?”

The Long Game

In 2023, MDT launched an initiative called the US-191/MT-64 Optimization Plan to address some of the hazards of the Gallatin Canyon section of Hwy. 191. The plan draws on data gathered from several assessments, including a 2020 US-191 Corridor Study, to identify five project proposals with the objective of making the roadway safer and more efficient for traffic and emergency response efforts.

Project nominations include proposals to add passing lanes in Gallatin Canyon, redesign pull-outs through the Canyon, reengineer the intersection of US-191 & MT-64, replace the Lava Lake Bridge, and complete a road restoration around Big Sky North (spanning from the US-191, MT-64 intersection to the Lava Lake structure).

Johnson notes that projects in the Optimization Plan are still only proposals. Each requires engineering, secured funding, and its own bidding process. All said, many won’t likely break ground until after 2030.

Unlike the maintenance projects, which are primarily state-funded, development and improvement projects are frequently eligible for federal funding designated under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). “It’s usually an 87/13 split—the US Department of Transportation provides 87% of the funds, and MDT covers the remaining 13%,” Jones explains. He says he’s not worried about funds drying up. “The IIJA Bill will expire next year, but we expect a reauthorization. The formula funding is a pretty safe funding category that pays for infrastructure, and it’s generally pretty apolitical.” Jones hopes to secure IIJA funding for most of the projects proposed in the Optimization Plan, including two designed to cut down on bottleneck congestion through the canyon.

At each mouth of the canyon, there are signs declaring “SLOW VEHICLES WITH 4 OR MORE FOLLOWING VEHICLES MUST USE TURN-OUT” as well as periodic warnings notifying drivers of upcoming pull-outs a quarter-mile ahead. However, most drivers overlook these signs, causing backups and prompting risky passing that endangers everyone.

While MHP does not have an officer specifically designated to patrolling the canyon, Samuelson says that officers working out of duty stations in Bozeman, Big Sky, and West Yellowstone all work in conjunction to monitor the stretch. “We’re partnering with MDT to promote highway safety,” Samuelson says. “We identify problem areas in our accident reports and exchange feedback on their engineering and our enforcement.”

Offering another solution to the ill-used pull-outs, one disgruntled Bozeman resident recalls submitting a letter to MDT in late 2022, suggesting the installation of “Slower Traffic Use Pull-Outs” signs dispersed throughout the canyon. He cited the repetition of other signs throughout the canyon, such as speed limits, and asked MDT why they thought a single sign in each direction was sufficient for the ensuing 22 miles. Rather than addressing the issue, he said that MDT “dismissed my suggestion with a wave of the hand, passing the buck to law enforcement.” He adds that a year and a half later, while weaving in and out of slower traffic, a reckless driver caused an accident near the northern mouth of the canyon, resulting in the death of a retired tourist from Arizona. His wife was injured, but survived.

“MDT dismissed my suggestion for more signage with a wave of the hand, passing the buck to law enforcement.” —Bozeman resident

The Optimization Plan does include a proposal to redesign pull-outs to be more user-friendly, as well as supplemental signage to encourage slow-moving traffic to utilize them. The proposal features sign mockups reading “SLOW VEHICLES MUST USE TURN-OUT 1,000 FT. AHEAD” and signs alerting drivers of upcoming pull-outs up to two miles in advance, significantly farther than current signage does.

Because the proposal is still in the early design phase, locations for signs and pull-outs have not yet been identified, but Jones says the project is expected to cost almost 11 million dollars.

The pull-outs project is being engineered alongside a $1.4-million passing-lane effort that would add three lanes—two northbound and one southbound—between mile markers 48 and 71. One southbound passing lane, however, will move forward sooner as part of the Spanish Creek Bridge Reconstruction project, scheduled to start in 2029. Still, Jones notes that neither the broader passing-lane package nor the pull-out project made it into MDT’s five-year plan, meaning motorists likely won’t see construction for several years.

Animal Crossings

Wildlife collisions account for 24% of all reported crashes on Hwy. 191, according to a 2020 MDT Corridor Study—2.5 times the state average and 5 times greater than the national rate.

A 2023 Wildlife & Transportation Assessment, published by the Center for Large Landscape Conservation (CLLC) and the Western Transportation Institute at Montana State University, identified a 5.6-mile stretch of Hwy. 191—from Gallatin Gateway to Spanish Creek—as a top priority location for a wildlife overpass. Using crash reports, carcass data, and GPS-collar tracking, researchers identified the Gallatin Canyon entrance as a daily crossing site for elk and other large mammals passing between the mountain terrain east and west of the Gallatin River. “It’s one of the last remaining open connections for elk moving across the valley,” says Elizabeth Fairbank, road ecologist for the CLLC. “Every time those animals cross the road, they’re in danger—and so are drivers.”

The proposed overpass would reconnect fragmented habitats and sharply reduce vehicle collisions. Similar projects, such as the Hwy. 93 crossings and fencing installation north of Missoula, have cut wildlife crashes by more than 80%, according to MSU’s Western Transportation Institute.

CLLC and MDT applied for federal funding through the Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program (WCPP), which supports projects that improve safety and habitat connectivity, but their proposal wasn’t selected in the first round, which Fairbank says drew five times more applicants than available funds. While they had hoped to reapply, federal delays could make the funding inaccessible for an extended period. The WCPP requires a 20% non-federal match, which Fairbank says has already been pledged by Big Sky–area donors, businesses, and conservation groups. “Everyone’s ready,” Fairbank says. “The land is secured, the engineering is done, and the community support is there. We just need the federal dollars.”

Wildlife crossings and fencing installations can cut wildlife crashes by more than 80%, according to MSU’s Western Transportation Institute.

The Gallatin Canyon site is especially well-suited for such a project: both sides of the highway are privately owned but permanently protected by conservation easements, and the landowners support construction. In addition, two recent pieces of state legislation—House Bills 855 and 932—establish a dedicated fund for wildlife crossings using marijuana tax revenue and specialty-license-plate fees, though it may take years for the fund to accumulate a sufficient amount.

Until then, Fairbank urges the public to support wildlife-friendly road projects during MDT comment periods. “Every comment helps,” she said. “This overpass would save lives and keep wildlife moving naturally through the landscape.”

Looking Forward

Long story short, the narrow, pothole-ridden stretch of Hwy. 191 that winds through Gallatin Canyon is full of driving hazards, but efforts to remedy them are being made—or are at least being talked about—by a variety of groups including MDT, CLLC, and MHP. However, despite a 20% increase in average daily traffic through the canyon in the past five years, collision counts have remained steady, actually dropping to a low of 36 reported crashes in 2024.

With the wear-and-tear caused by weather and heavy traffic flows, coupled with limited manpower and budgets, large-scale improvements to the roadway will inevitably be a slow burn. In the meantime, motorists can do their part by utilizing pull-outs, driving at safe speeds, checking weather reports, and voicing their opinions during public-comment periods for project-engineering phases. As for unexpected eventualities like Hockett’s head-on collision, all we can do is cross our fingers and hope that solutions come sooner rather than later, before Gallatin Canyon claims more lives.