A Venusian Spring

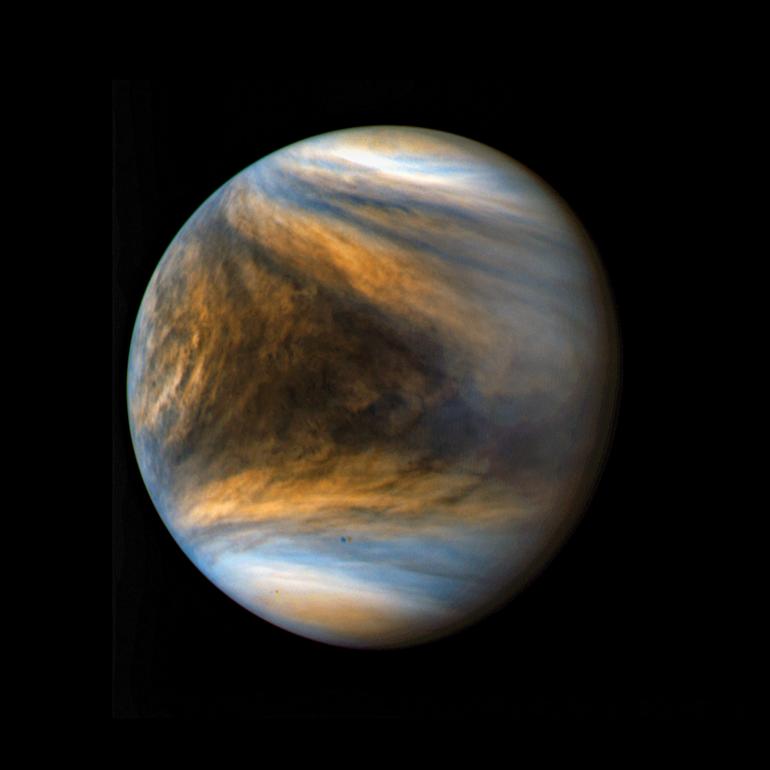

The celestial apparition shining in the west.

Let’s face it: it’s never spring on Venus, where the surface temperature under those heat-trapping, sulfuric acid-laced clouds is a toasty, lead-melting 850 degrees Fahrenheit the whole year. For that matter, it’s rarely spring in Montana, where we go directly from snow, to mud-and-flood, to “summerish” within a two-week window.

But this year we can contemplate both circumstances together, for it will be a Venus spring. Earth’s hot sister, named for the Roman goddess of love, will be looking for love in all the right places (to misquote the old Johnny Lee Urban Cowboy country song), shining brightly as she hits every happy hour in the evening western sky.

Earth’s hot sister, named for the Roman goddess of love, will be looking for love in all the right places.

The planet, whose proximity in an orbit just sunward of us and whose reflective veil of clouds make it so eye-catching, actually slides into the night sky in the western dusks of winter. On March 1, Venus and Jupiter briefly snuggle low in the west after sunset—passing ships as the more distant Jupiter bows out of the night sky and the nearer Venus makes its entrance. It’s the first celestial tryst of many.

A few days into the spring calendar, Venus is higher in the sky at sunset, and is joined by the crescent moon, below it (and much closer in space) on March 22, and above it on March 23. On and around April 11, Venus coasts past the much more distant Pleiades star cluster. Let it get a little darker and then use binoculars to see both to good effect.

On the evening of April 22, Venus is again in rendezvous with the crescent moon, the two making a fetching triangle with the red star Aldebaran—the fiery eye of Taurus the bull. Three nights later on April 25, you can find the moon next to the red fleck of the planet Mars.

Following a month’s breather, Venus again hooks up with the crescent moon on the nights of May 22 and 23 (the moon dallying with nearby Mars again on May 24).

The final spring fling occurs on June 21—the summer solstice, actually—when Venus, the much fainter Mars, and the crescent moon make another celestial triangle in the west.

Then the hayrides begin. On the evenings of June 1 and 2, Venus lines up with Castor and Pollux, the stars marking the heads of the Gemini twins. But cast your binoculars just up and a little left and you’ll find planet Mars rolling around in barn furniture. It sits inside a square of stars that marks the body of Cancer the crab, among a sprinkle of stars called the Praesepe, whose name is Latin for “manger.” The cluster acts as the hay filling the four-star feed trough. It’s also called the Beehive Cluster, and was one of the first objects Galileo observed in the early 1600s with optics inferior to your binoculars.

Mars exits the manger after a few nights, only to have Venus jump in on June 12 and 13, making yet another lovely binocular sight as the bright planet upstages the cluster of about 1,000 stars a little over 600 light-years away.

The final spring fling occurs on June 21—the summer solstice, actually—when Venus, the much fainter Mars, and the crescent moon make another celestial triangle in the west. Venus will have reached its greatest elongation from the sun on June 4 as we look at them in our sky, so by then it will be swinging around in its orbit to pass between us and the sun. But it will stay visible, though lower and lower in the evening sky, until the latter part of July.

It was Tennyson who wrote that, “In the spring a young man’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love.” Ditto for a young woman, perhaps. And both will have the encouragement of the celestial apparition of love shining in the west, in what passes for spring in Montana. Enjoy the view!

Jim Manning is the former executive director of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. He lives in Bozeman.