The Sky Wrangler

Western mythos is filled with rootin’, tootin’, straight-shootin’ cowboys—ridin’, ropin’, wranglin’ and rough-housin’ their way into the stuff of legend. The ancient Greeks would have appreciated the type, for they had their equivalents, some of whom are memorialized in the sky. Take Perseus, for instance, who rides the northeast in autumn.

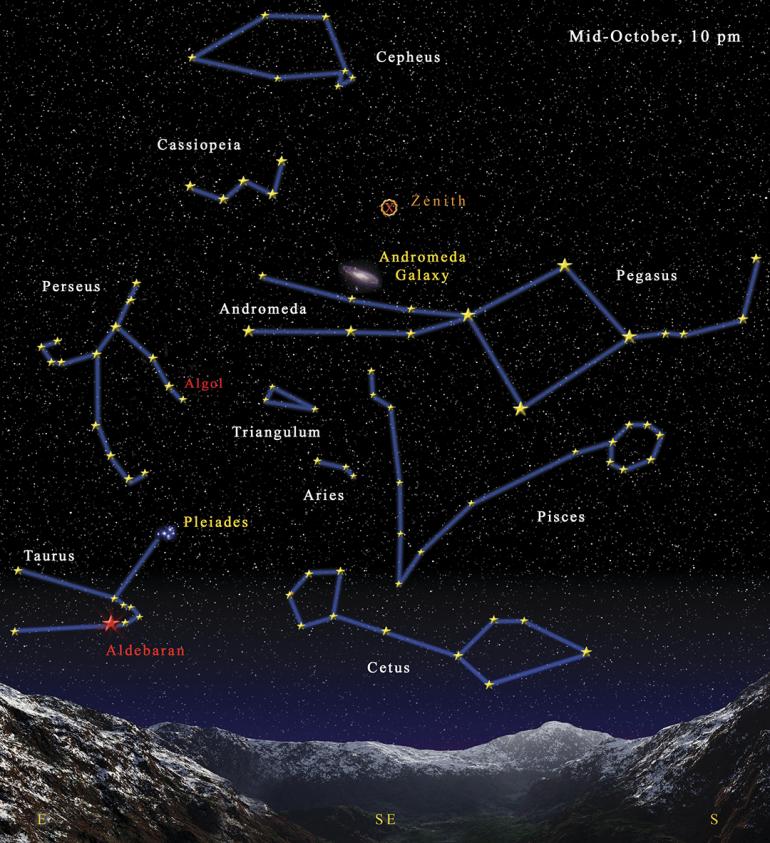

To find the rambunctious hero, first find the Great Square of Pegasus, the flying horse, who flies just south of overhead in the middle evening. Trace along the brighter, lower curve of Andromeda’s stars, anchored to Alpheratz (the upper left star of the square), and jump one more star along this curve into the middle of the gangly K-shape of Perseus.

Perseus was born under a favorable star. More specifically, nine months after a shower of gold—the form in which the god Zeus visited his mother Danae one night. Danae’s father, King Acrisius of Argo—having received a prophecy that his grandson would one day be the death of him—promptly set mother and child adrift on the sea in a chest. But the gods guided the vessel to the shores of Seriphos, where the fisherman Dictys adopted them as his own.

Perseus grew tall and strong—even as Dictys’ brother, King Polydectes, grew enamored of Danae. To get the protective Perseus out of the way so he could pursue Danae, Polydectes staged an engagement to another and insisted that the only wedding present worthy of Perseus was the head of Medusa, one of the Gorgon sisters, who had snakes for hair and whose stare could petrify living flesh.

Perseus, ever game, accepted the challenge and set off. On the way, his family connections paid off with presents from the gods: a brass shield from Athena, a diamond sword from Hephaestus, winged sandals from Hermes, and a helmet from Hades that made him invisible. Thus armed, Perseus flew to the northern home of the Gorgons in his sandals, put on his invisibility helmet, and sneaked up on Medusa while she slept, looking only at her reflection in his shiny shield before lopping off her head with the sword.

From Medusa’s blood sprang Pegasus, the winged horse. And while some versions of the story say Perseus wrangled the horse and rode him to fame and fortune, Pegasus actually flapped off to other adventures. Perseus didn’t need Pegasus; he had his sandals to get him around.

And so he did—and had no compunctions about using his grisly trophy. When the titan Atlas refused him hospitality on the way back home, the peeved Perseus showed him Medusa’s head and turned him into the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. When he spied the princess Andromeda chained along the eastern Mediterranean shore, a sacrifice to the sea nymphs for the intemperate bragging of her mother, Queen Cassiopeia (who claimed she was prettier than said nymphs), Perseus used Medusa once again to calcify Cetus, the monster who had arrived for lunch. And when he arrived back in Seriphos, he confronted the black-hearted Polydectes, proffered his present, and turned the king and all his court into assorted minerals.

Perseus and Andromeda married and raised a royal family of their own. And yes, poor Acrisius fell prey to the prophesy that started Perseus’ adventures when he walked into an errant discus tossed by his grandson at a sporting event.

Ultimately, Perseus and Andromeda were immortalized in the sky, along with her parents Cassiopeia and Cepheus, Pegasus, and Cetus. But Medusa’s head ended up there as well; you can see her two glittering eyes as stars in the outstretched hand of Perseus—at the end of the arm of the "K." The brighter star, Algol, is an eclipsing binary; every three days, it temporarily dims to a third its normal brightness over several hours. Although Medusa’s expression no longer turns people to stone, be careful; one crisp fall evening, she may just wink at you from the grasp of the wrangler in the sky!