Light Show

Celestial gatherings in the autumn sky.

Fall is rendezvous time. Birds flock and head south. Bison and elk head for lower elevations. Cattle are rounded up for their winter pastures.

The sky offers a rendezvous of its own this season in the form of a striking evening conjunction of the two brightest planets in the heavens during Thanksgiving week, with more guests coming to the table as the week progresses.

The best evening to look will be November 24. Bundle up and head out about a half-hour after sunset (around 5:15pm) and seek an unobstructed southwestern horizon. If the sky is clear, Venus and Jupiter will begin to show as darkness falls, as two bright star-like objects—Venus considerably brighter—close together just above the horizon.

The planets are not actually close to each other, of course; we just happen to see them along the same line of sight as they move along their orbits around the sun. Venus is the foreground planet, about 150 million miles away as it emerges from the far side of the sun; Jupiter lies more than 400 million miles farther away across the solar system.

Watch them slowly separate in the evening sky from night to night as Thanksgiving approaches. On Thanksgiving night, November 28, the sliver crescent moon joins the pair just above the southwestern horizon, with the even more distant Saturn lying just above and to the left of the trio. On the 29th, the moon will have shifted its seat at the table to sit next to Saturn, or so it appears. The moon in fact is a mere quarter-of-a-million miles from us, give or take, while Saturn is nearly a billion miles away. Like estranged relatives at holiday gatherings, they may seem proximate, but they still keep their distance.

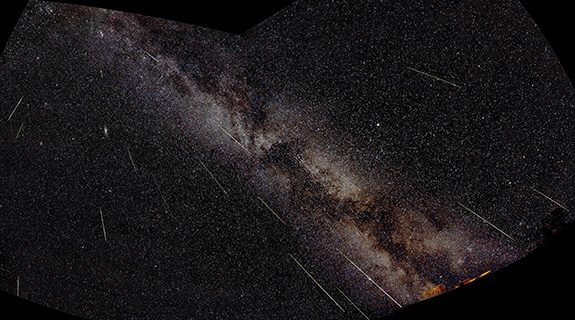

The fall also hosts annual sky gatherings in the form of regular meteor showers. On the night of October 21-22, the Orionid meteors streak across the sky, appearing to come from the direction of the constellation Orion, which rises around 11:30pm These “shooting stars” are bits of dust shed from Halley’s Comet, whose orbit Earth encounters every year at this time.

On the night of December 13-14, Earth comes into rendezvous with another debris stream—this one shed by the asteroid Phaethon—to produce the annual Geminid meteor shower. In this case, the meteors appear to radiate from the constellation Gemini, which rises around 7pm.

The Geminids are more prolific, producing up to 100 meteors per hour under excellent conditions compared to the Orionids’ 20 or so; but in both cases this year, substantial moonlight will wash out the fainter ones. Both produce many bright meteors that should still be visible, and these celestial gatherings happen much closer than planetary conjunctions—this space debris burns up just 50-70 miles over our heads.

So this fall, go out and rendezvous with the sky and enjoy the celestial treats that lie over our heads before winter sets in.

Jim Manning is the former executive director of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. He lives in Bozeman.