Trail Boss in the Sky

Winter’s starry nights.

If John Wayne were a constellation, he would be Orion.

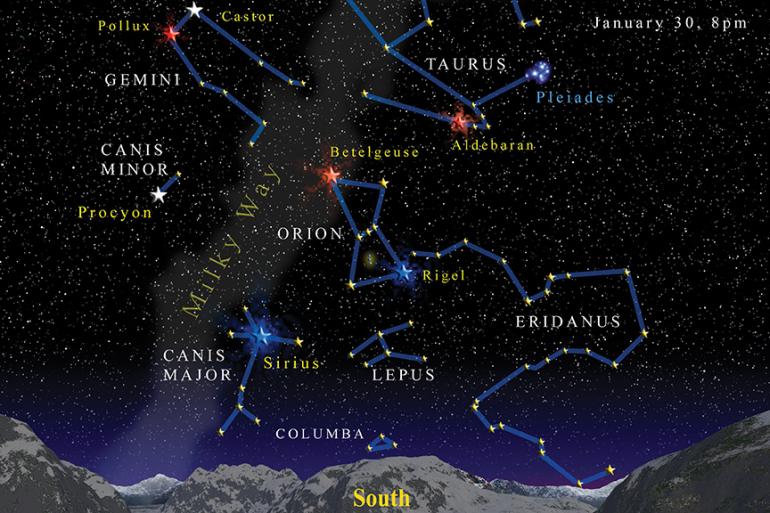

Big, bold, larger-than-life, and easily identified, Orion rides the trail every clear night of winter, high in the southeast by 9pm around New Year’s, due south by the end of January. Look for his striking slanted belt of three prominent stars and the fainter line of three below it marking his sword, enclosed by a rectangle of bright stars (orange Betelgeuse, an old bloated supergiant, marking his right shoulder, and blue-white Rigel marking his left knee).

It doesn’t take much to see this stellar celebrity as Wayne in his role as the trail boss in the movie Red River, the belt and sword making his gun belt and six-shooter, trailing his “doggies” across the sky. Well, one doggie at least: long-horned Taurus the bull, who backs up in front of him as they ride west.

Not all cultures saw a strapping hero in these stars; the Lakota made of it a hand with the belt as its wrist, and the Chinook nation saw the belt and sword as two canoes chasing a prize salmon: Sirius, located down and left of the canoes, fiercely burning as the brightest-appearing star in the sky.

But many cultures made this pattern into one of their legendary figures. To the ancient Sumerians, he was Gilgamesh fighting the Bull of Heaven (the aforementioned Taurus); to the Puebloan Tewa tribe, he was Chief Long Sash who led the people in a migration across the sky. The Navajo saw here First Slender One, a protector who kept an eye on the Pleiades star cluster as a group of children. The Chinese saw the great warrior Shen. The sharp-eyed Blackfeet also placed one of their mythic heroes here: Blood-Clot, the monster-slayer, but they didn’t use the whole pattern. Blood-Clot became “Smoking-Star”—the hazy patch in the middle of the sword where the glowing Orion Nebula lies.

To the Greeks, Orion was the son of the sea god Poseidon in some stories, at home as much in the water as on land where his hunting exploits became legend. But the storytellers gave him feet of clay; his skill made him something of a braggart, and he was exceptionally unlucky in love. One tale tells of how he became enamored of Princess Merope of Chios. When he pressed his suit beyond the bounds of propriety, her father King Oenopion had him blinded and sent him wandering into the world. Orion made a pilgrimage to Helios, the god of the sun, and was cured of his infirmity—just in time to fall in with Artemis (the Roman Diana), the virgin goddess of the moon and the hunt.

Diana was a match for Orion on the hunting trails, and the two carried on an allegedly platonic relationship. But Diana’s brother Apollo disapproved, fearing for her virtue. So one day when he found his sister alone, he teased her that she wasn’t good enough to hit a small black speck bobbing on the ocean. She was, however. She stretched her bow, and shot the target true. Only later did she learn that the speck had been the distant head of Orion as he took a dip in the sea.

Too late to revive him, Diana did the next best thing: she had him placed in the sky where we find him today—near enough to the monthly track of the moon for Diana to pass by and tousle his hair. He still hasn’t learned his lesson, for now he pursues the lovely Seven Sisters—the Pleiades—as they perch on the shoulder of Taurus. If he tires of that chase, Lepus the hare crouches just below him, ready to run, and his two hunting dogs, Canis Major (with Sirius) and Canis Minor lap at his heels.

And so Orion swaggers still, boss of his own trail across the winter sky. Next clear night, go out and give him a hearty “Howdy, Pilgrim,” and enjoy the thrill of the hunt!

Jim Manning, formerly the executive director of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific in San Francisco, lived outside Bozeman for many years and has returned to live here again.