Casting Curfew

Understanding how hoot-owl restrictions work.

When the clock strikes two on a summer afternoon, as the sun’s rays beat down and the water temperatures climb, nets are put away, fly boxes are closed, and the fish swimming down below are left to rest and recover.

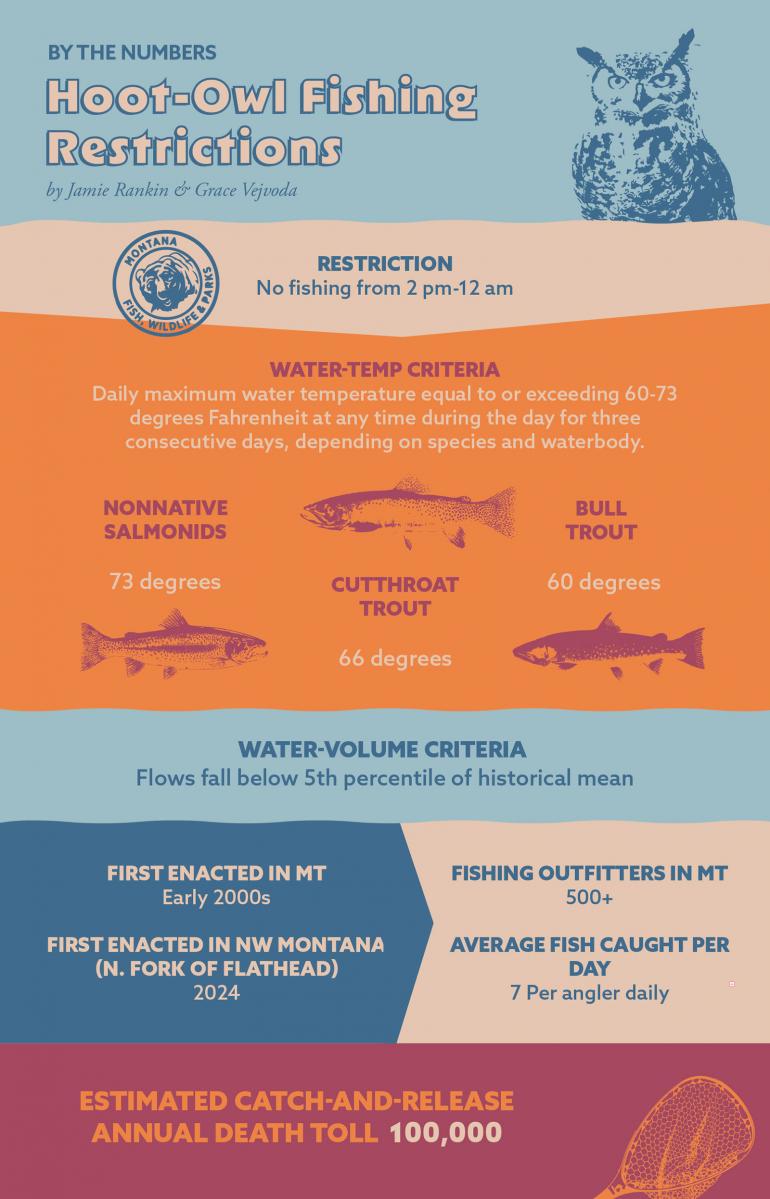

As Montana summers become warmer and drier, fish populations are feeling the heat. Warmer water temperatures lower dissolved oxygen levels, putting fish in a stressful spot. The struggle for survival is tough enough as-is, and when fighting a hook is factored in, fish become more vulnerable to over-exhaustion, disease, and predation. In addressing this issue, Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks (FWP) first introduced “hoot-owl” fishing restrictions in the early 2000s.

It’s up to all Montana citizens, not just anglers and other river users, to take some responsibility for the creatures that make Montana such a prized angling destination.

The term originates from the early logging days, when loggers, who faced hot and dry summer conditions, would wrap up their work in the afternoon. They did this to not only protect themselves, but also to prevent equipment from emitting sparks that could ignite a forest fire. Loggers kicked off their workdays in the early, cooler hours of the morning, and during these first hours of the day, were accompanied by the hooting of their nocturnal neighbors—owls.

Hoot-owl restrictions permit anglers to fish in the cooler hours of the day, but fishing must cease from 2pm until midnight. This restriction is meant to protect all fish, but especially those that aren’t as hardy and are much more sought-after—specifically, trout.

There are a lot of factors at play for FWP to determine when to lay down the hammer. Fisheries biologists make the call if and when an appropriate combination of the following criteria is met: river temperatures reach 60-73 degrees Fahrenheit (restrictions vary by fish species) for three consecutive days; river levels fall below the fifth percentile for the average flow on record; waterbodies exhibit symptoms of pollution, disease, and/or drought. Biologists also keep a close eye on dissolved-oxygen levels and measure them daily before sunrise. If these are equal to or less than 4ppm (parts per million), fishing closures are emplaced.

“We have weekly drought meetings with staff from across the state that typically start in May,” explains Mike Duncan, FWP’s Region 3 Fish Manager, “which is well before we typically see concerns flows and water temperatures. We also take angling pressure, weather forecasts, and the potential for angler displacement into account when deciding whether to implement or lift restrictions and closures.”

Along with monitoring water temperatures, flows, and oxygen levels in the water, FWP also examines each waterbody’s irrigation (to see if cold water can be added), removes river obstructions, and maintains streamside vegetation where fish seek shaded shelters to keep cool. Enacting hoot-owl restrictions is “a last resort, and only when it looks like trout on a river are really in trouble,” says Duncan. FWP keeps an eye on these factors daily, and retracts the restrictions as soon as river concerns abate.

Depending on temperature and flows, specific sections of river will be restricted, but other times, the entire river goes under a hoot-owl curfew. In the summer of 2024, hoot-owl limits were already in play in early July along the entire length of the Big Hole, East Gallatin, Bitterroot, and Jefferson rivers, while several sections on rivers across the state were closed, such as the Smith, Beaverhead, Ruby, Sun, Gallatin, Madison, Clark Fork, and Blackfoot.

Although it does take a toll on outfitters’ trips by limiting their guiding hours and income stream, the regulation is mostly met with acceptance. Most guiding operations acknowledge these short-term losses are outweighed by the long-term sustainability of Montana’s fish populations. Says Brant Oswald, senior advisor of the Fishing Outfitters Association of Montana, “Most guides and outfitters voluntarily initiate their own restrictions, fishing early and ending early whenever water temperature and flow become an issue. We try to be proactive and change our behavior before regulations require it, for the good of the fishery.”

Loggers kicked off their workdays in the early, cooler hours of the morning, accompanied by the hooting of their nocturnal neighbors—owls.

As hoot-owl restrictions spread across Montana’s rivers, questions have arisen regarding regulations on catch-and-release vs. catch-and-keep practices. One may wonder, If I’m planning on keeping the fish anyway, why can’t I just fish whenever? The answer is simple, really: one cannot guarantee what will bite the hook. Meaning, an angler may hook a fish that is unable to be kept, either due to minimum size requirements or it being an off-limits species. Also, if a fish is lost before being netted, it may suffer the same over-exhaustion that hoot-owl rules are trying to prevent.

At the end of the day, there’s a lot more to be done for our rivers beyond FWP’s hoot-owl restrictions, such as less dewatering by irrigators. It’s up to all Montana citizens, not just anglers and other river users, to take some responsibility for the creatures that make Montana such a prized angling destination. After all, everyone benefits from Montana’s reputation as a fly-fishing fantasy land. And where’s the magic in angling if there’s no healthy fish left to catch?