The leave-no-trace legacy of a wilderness ranger.

When I was little, I didn’t know them as the Beartooths, just the mountains. On the last day of school, my family would pack our station wagon to the gills and head to the mountains. Our home was in the East Rosebud Valley. School, and our house, were in Wyoming, but that wasn’t home, at least not for me.

I was the little tyke, the youngest. In my early years, my family did some of the longer, harder hikes without me. I couldn’t wait to join them. My parents were newbies in the hiking and backpacking world, and the stories they tell of those first trips are a testament to endurance, not to any backcountry knowledge. Our family really knew nothing of distance (how far is too far to go with a heavy, ill-fitting pack and hand-me-down boots?), proper gear, or how to leave no trace. We cooked all our food over a fire and didn’t see a need for a stove.

This is the tale of how one man single-handedly changed our world—and how his influence lives on, to this day.

After one particularly rough trip, my dad bought us all state-of-the-art Jansport frame packs—which were top-end back then. We all got new hiking boots, the huge Tecnica waffle-stompers that took a year to break in. My mom, a talented seamstress, made us all waterproof ponchos that draped nicely over our packs. Even the dogs got little rain jackets. I think I was five or six when I joined them with my good gear. I was so tiny, though. I remember having to tie a huge sweatshirt around my waist to get my backpack waistbelt to fit. But the strongest memories are of camping at Rainbow Lake and Lake at Falls, fishing for days. I had a little breakdown casting pole. Someone would help me tie on a good fly and a bobber. Man, I would slay ‘em.

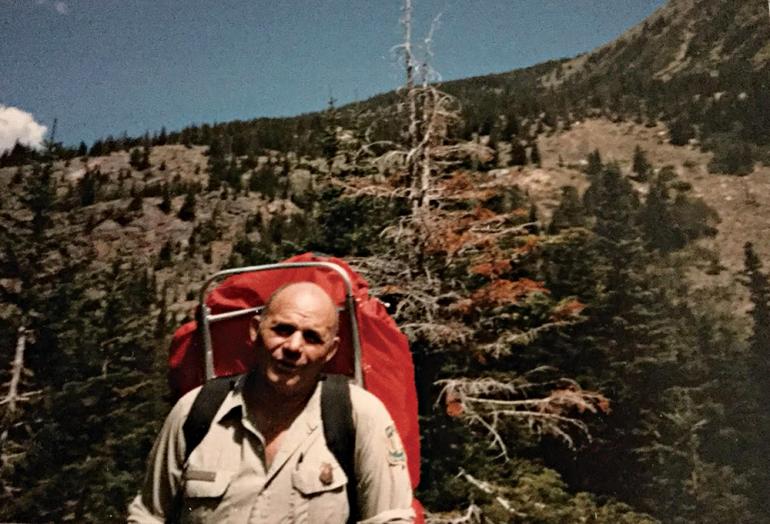

On one of these trips, we met a wilderness ranger named Blase DiLulu. He was intimidating at first, especially to a tiny girl. Bald head, barrel chest, sleeves rolled up to reveal massive forearms and veins, gigantic pack, loud voice, and not shy at all. I probably ran and hid someplace during this first encounter. But he changed our lives. He taught us the skills and mindset we needed to not only fully experience the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, but to help protect it for generations to come. Blase taught us the correct way to pick a campsite, protect water, dig a proper firepit, and to carry out other people’s trash. My family took this to heart.

My dad, a meticulous engineer, embraced leave-no-trace ethics with fervor. From the day we met Blase, each firepit he dug, the sod was carefully carried to a nearby water source so it would stay fresh until we replaced it. Before breaking camp, he scraped the cold ash and coals from the pit and scattered them widely. The pit was refilled with additional soil we’d stored in a clean bag. Then it was covered with the sod we’d kept fresh. Dad would even find a small tree or berry bush to plant near the replaced sod, an attempt to give back as much as we were given.

We learned to place our tents in ways that minimized damage to vegetation. We hung our food bags precisely, and paced off a healthy distance between our latrine and the nearest stream. Before leaving camp, Dad straightened rose bushes and elk thistle, then brushed the camp so it looked as though we’d never been there. It was a challenge he accepted gladly.

Mom served as Blase’s sounding board for many years. Whenever he joined us at camp, he’d sit with us by the fire, drink coffee, and tell stories. These conversations would be the spark plug for Mom’s future role in helping establish East Rosebud Creek as a Wild & Scenic River.

As far as we’re concerned, Blase is still the keeper of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness.

There were deep discussions of long-term protection of the woods, most of which made no sense to a kid, but Blase was passionate—and loud. If we were at our cabin on the East Rosebud, we’d hear the loud stomp of his gigantic hiking boots on the porch, and Blase would stick his head in the door and ask if the coffee was on. He told stories of moving illegal camps, bear encounters, and fish. Always fish stories. He wasn’t a great speaker, but his enthusiasm spilled from his massive veins and into his stories. If his pack was too full to take out all the garbage, he’d stop by and ask us to help him. At times, he would chase people clear to Billings, or wherever they were from, and bring them the garbage that they left at a campsite. That was his passion: to teach people the correct way, even if it meant chasing them down. My mom has carried his work ethic through her life, now 80 years.

My brother had an ongoing fishing contest with our ranger friend. Blase would hint where the fishing was good, but not say exactly where. My brother remained determined to find it and catch more and bigger fish than Blase did. I’m not certain who ever won the challenge, but what a way to get a teenage boy to cover the territory, spend quality time fishing, and learn to love the Beartooths. One afternoon, meeting at a high lake, Blase mentioned that there was a huge lady rainbow trout waiting in a lazy stream not too far away. Of course, my brother took off like a flash. As we watched him go, we asked Blase how he knew it was a girl fish. Blase grinned like the big imp that he was and fed us the line, “Why, the pink spots, of course.”

My sister was always blowing Blase’s mind with the food she prepared in the backcountry. She baked crazy stuff in the backcountry, and it was crazy good. The best was always cherry pie, and it became a ritual to hide a can of cherry-pie filling in someone’s sleeping bag, so they could carry the extra weight to camp without knowing. Blase changed his callout when entering our camp from “Ranger coming through!” to “Looking for cherry pie!”

Growing up, my sister and I had challenges for Blase. The first was to see if he could find where we had pitched a camp. Though we tried so hard to make it invisible, to not leave a trace, he always guessed right, which amazed us. It was as if he knew every rock, every flower, every blade of grass in those mountains, and where they belonged.

That was his passion: to teach people the correct way, even if it meant chasing them down.

We also had a challenge to see how many fire rings we could reclaim in one trip. Even now, the reclaiming of fire rings is a habit; my sister and I don’t even talk about it. We just get to it. Those fire rings stand out as visual scars, reminders of people who just don’t know any better. The fire-ring challenge will go on forever, even though Blase isn’t around physically anymore. As far as we’re concerned, he’s still the keeper of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness.

We have chosen to live and raise a family in these mountains, with a passion to pass on the caretaking of the Beartooths. Our family business in Red Lodge, which sells outdoor gear, has been defined by that ethic since we opened. We have direct contact with people who visit the mountains, teaching the value of quality gear and the items they need to have a great experience. We stress leave-no-trace methods and bear safety. We help folks plan trips, point out legal camping areas on the maps, teach them how to hang their food properly, urge them to use a camp stove instead of a cooking fire, and explain the correct way to have a fire without leaving a mess. We’ve chosen to donate staff hours, money, and gear to nonprofits that promote conservation of the Beartooths.

Blase often worried about who would take care of these woods after he was gone. I wish I could have told him back then not to worry, that all his lessons didn’t fall on deaf ears. Living in Red Lodge, we know that we have the best back yard in the world—and we intend for it to stay that way forever. Blase showed us how, and we paid attention. We do all we can. Even if he did scare the bejesus out of me as a tiny girl.

Marci Dye lives and works in Red Lodge, running a family business, Sylvan Peak Mountain Shop. Her days are spent educating people on backcountry use, providing essential gear and supplies, and teaching kids to love the outdoors. This essay originally appeared in Voices of Yellowstone's Capstone: A Narrative Atlas of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness.