Joe Brooks, A Man For Montana

The story of one of America's most famous fishermen.

A single conversation can alter not only one life but also the lives of generations of anglers and even the economies of entire states.

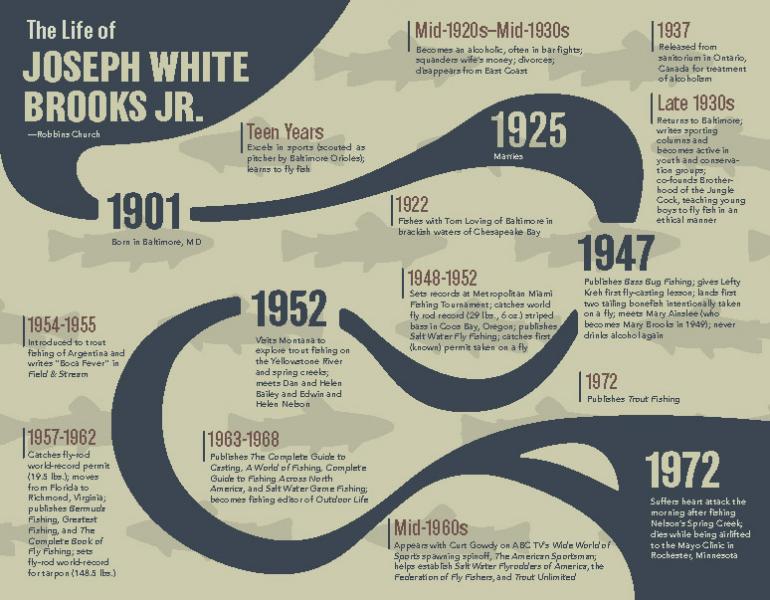

One day in the winter of 1951-52, a lion hunter from Livingston, one Arnold Schueren, appeared at the Miami Herald, where Joe Brooks had office space while he managed the Metropolitan Miami Fishing Tournament. Schueren asked Joe if he would make a trade with him—an autographed copy of his book on lion hunting, Foxy’s Lion Tales, for a signed copy of Joe’s first book, Bass Bug Fishing. In their conversation, Schueren asked Joe where he and his wife Mary spent their summers. “Come visit us in Paradise Valley in Montana,” Schueren said, “and I guarantee you will never go anywhere else.”

The rest is history.

In the summer of 1952, Joe and Mary drove to Montana to see for themselves. One visit was all it took—they spent at least three months there every year afterward until Joe died 20 years later.

Their first summer, Scheuren introduced them to Dan Bailey, who introduced them to Edwin and Helen Nelson, owners of a nearby ranch through which flowed a beautiful spring creek, now known worldwide as Nelson’s Spring Creek. For the next five years, Joe and Mary rented a rustic bunkhouse cabin on the Nelson ranch from June through October to be close to the creek and their new friends. This location was to serve as a basecamp for their other Montana fishing.

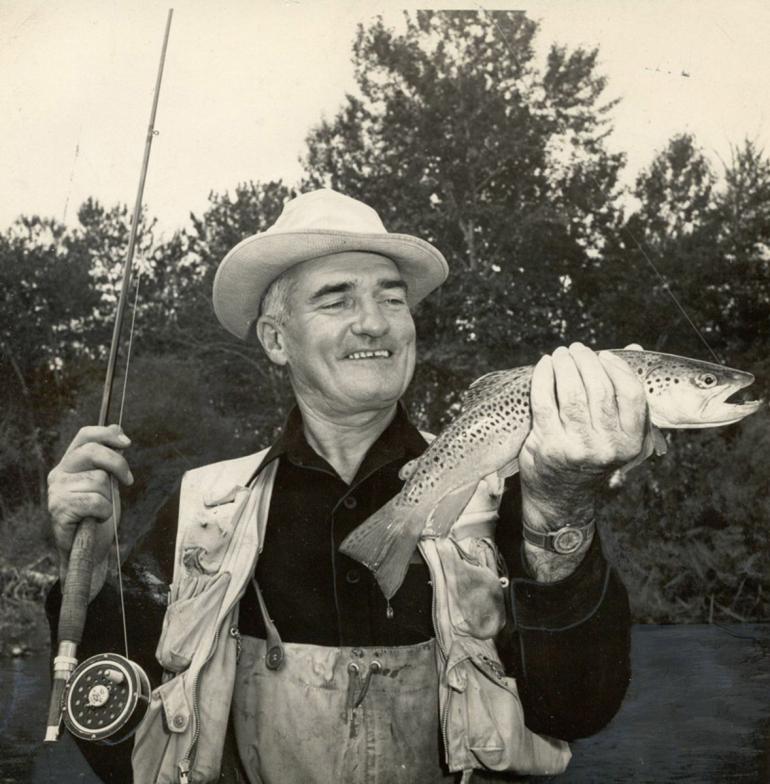

In a 1956 profile of Joe Brooks in Collier’s Magazine, Curt Gowdy noted that Joe “traveled some 75,000 miles a year,” fishing the best spots in the world. Gowdy laid out a month-by-month calendar of where Joe would be and for which species he would fish. And where would Joe go for trout in the Lower Forty-Eight? Montana.

Joe and Mary loved the Nelsons’ creek and the other spring creeks in the Livingston area, but they also loved fishing many of Montana’s other streams, rivers, and lakes. In his 1957 book Greatest Fishing, Joe tells the tale of a harrowing horseback trip to fish Aero Lake at 11,500 ft. for stocked brook trout. In his 1956 article, Gowdy included a photo of Joe netting a large rainbow trout in Big Moose Lake. It didn’t take Joe long to make Montana one of his favorite destinations.

In my late teens and early 20s in Richmond, Virginia, my family lived close to Joe and Mary, and I came to know them through my close friend Marvin Williams. Marvin and I visited them often when they were at home. In Joe’s cozy basement study, he had mounted souvenirs of his fishing adventures, including a scale from his world-record 148.5-lb. tarpon and his first three permit—but only one mount of a freshwater fish. That mount resided on the wall beside his desk, hovering over his typewriter and papers. It was a rainbow trout of about five pounds from the Yellowstone River, not huge for a Joe Brooks–caught trout, but memorable for its fight—it jumped 14 times.

In close competition with Nelson’s as Joe’s favorite Montana river, was the Big Hole, perhaps because of its brown trout, a species that Joe relished because of the angling challenges it provided.

I recall a couple of outings on the Big Hole with Joe, fishing with friends Marvin Williams, Bert Lindler, and Cam Sigler—all of us mentored by Joe in our fly fishing. There, on the Big Hole, Joe seemed somehow to be more relaxed and more open about his past demons—demons detailed in the documentary Finding Joe Brooks. The Big Hole was a special place for him.

In the late 1960s, coal-mining interests revived interest in building a dam on the Yellowstone River, just upstream from Livingston at the Allenspur Gap. That dam would have flooded the river for 30 miles and devastated the fishing and ranching community of Paradise Valley. Joe was one of many conservationists who worked to oppose the dam. And, in this case, the conservationists won.

Suffering from heart disease near the end of his life, Joe spoke to Cam and Bert about what he knew was coming. He confided to both that he wanted to die with his fly rod in hand, facing upstream. He came as close to that wish as any of us might come. His last fishing was on Nelson’s Spring Creek in late September 1972. Not feeling well, he left the stream and put away his fly rod for what turned out to be the last time. The next morning, he suffered a heart attack and, the day after, died while being airlifted to the Mayo Clinic.

After Joe’s death, Mary moved from Richmond to Arizona to golf with friends and to write stories and poetry for the local newsletter. When she could no longer golf, she returned to Livingston to spend her final years close to the Nelsons and to Joe’s grave.

Joe and Mary are buried in Parkview Memorial Gardens close by the Yellowstone along East River Road, just south of Livingston. The views from their graves are grand. The Absaroka Mountains rise to the east, and down the slope towards the Allenspur Gap, the Yellowstone River, still undammed, rolls on.

Joe Brooks and his wife, Mary Ainslee Brooks, were born thousands of miles from Montana, Mary in Ontario, Canada, and Joe in Baltimore, Maryland. They traveled the world for fishing adventures, saw many beautiful places, and met many wonderful people, but they always came back to Montana—back to the country and friends they loved best. Here they are at rest—sojourners come home at last.