Clearing the Fields

A new method to reduce elk damge.

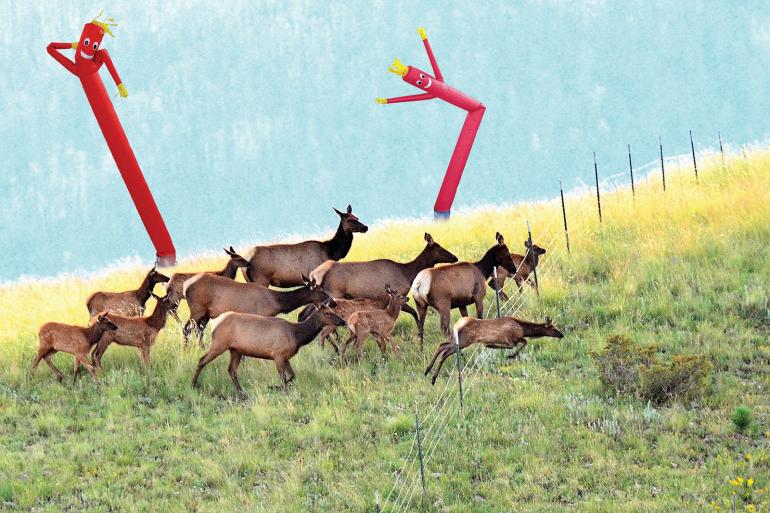

Next time you’re driving through Montana’s wide-open ranchlands, you might see something peculiar waving in the distance. Getting closer, you make out a large cylindrical object flapping around. You vaguely recognize its jolting movements. Wait a second, are you losing your mind? Surely, that’s not one of those inflatable tube men you see at car dealerships?

Worry not, your sanity’s intact—it is a tube man. But no, there’s not a used-tractor sale taking place in someone’s back 40, nor is part of the latest heckle-a-rancher TikTok challenge. This is the state’s latest effort to help landowners protect their crops from wintering elk. “All the methods we’ve used to deter elk from agricultural land are inconsistent at best,” Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks wildlife biologist Dee Coye says. “It was time to think outside the box.”

Outside, indeed. But, wacky waving tallboys? Where did that idea come from? Coye explains the thought process: “My cousin Eddie works at a car lot in Miles City, and he put up one of those sky dancers to help the boy scouts with their annual Rocky Mountain oyster sale. All the local cats freaked and ran off. I was standing there, testing the testes, and a light bulb went on inside my head.

Here’s the thing: every winter, thousands of elk move out of the snow-filled mountains and onto the valley floor, where ranchers grow hay and graze cattle. Elk find these spots irresistible: there’s little to no hunting pressure, and predators are neutralized by the ranchers. It’s a safe place to munch on high-calorie hay, all conveniently bundled and stacked in place. It’s basically a Golden Corral for elk.

“All the methods we’ve used to deter elk from agricultural land are inconsistent at best,” Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks wildlife biologist Dee Coye says. “It was time to think outside the box.”

But those haystacks aren’t big enough for elk to act like four-legged socialists and just help themselves to the bounty. “They’re eating my damn paycheck,” says rancher Noah Entrie. “My cows’ll starve without enough hay, and then me and my family’ll be next!” He acknowledges that FWP offers assistance for this kind of wildlife conflict, including damage hunts, hazing, and stackyard fencing, with hunting being the most effective deterrent. But he’s not on board. “I don’t like it,” says Entrie. “Not one bit. This is my land, and I’ll be damned if anyone else is gonna hunt it. I mean, what’s next? Soon they’ll be knockin’ on my door, askin’ to lay with my wife. Darn woman would probably do it, too. She’s still ornery from the time I got flirty with that farrier behind the stockyards.”

Which is where the tube men come in. Elk are prey animals; their sight is sensitive to peripheral movement. Flapping, floundering, 30-foot-tall figures scare them away on a large scale. “Montana is pioneering this new method,” Coye says. “And we’ve already gotten promising feedback.” One program participant, Elle Kargon, hasn’t had an elk on her ranch in weeks. “That big red weener-lookin’ thing done run ‘em off,” she says. “But it also scared the crap outta my horse. I got bucked off good. Then I had to tell some silly 6-platers to get lost, there wasn’t no damn mattress sale goin’ on out here.”

Only time will tell if the “scarebros,” as they’re being called, will be an effective long-term solution. In the meantime, United Property Owners of Montana (UPOM) has threatened a lawsuit, claiming that FWP should be using more specialized tube men. “It’s a private landowner’s God-given right to sell the public’s constitutionally-guaranteed wildlife to the highest bidder,” reads the UPOM complaint. “And it’s FWP’s duty to protect that right with tube men that only scare off cows, not trophy bulls.” Especially now, the complaint added, when the demand for elk-antler chandeliers in Big Sky is at a historic high.

To learn more about the program, visit scarebros.org.